Meet the Long Beach artist fighting for Latinx farmworkers and their legacies

- Share via

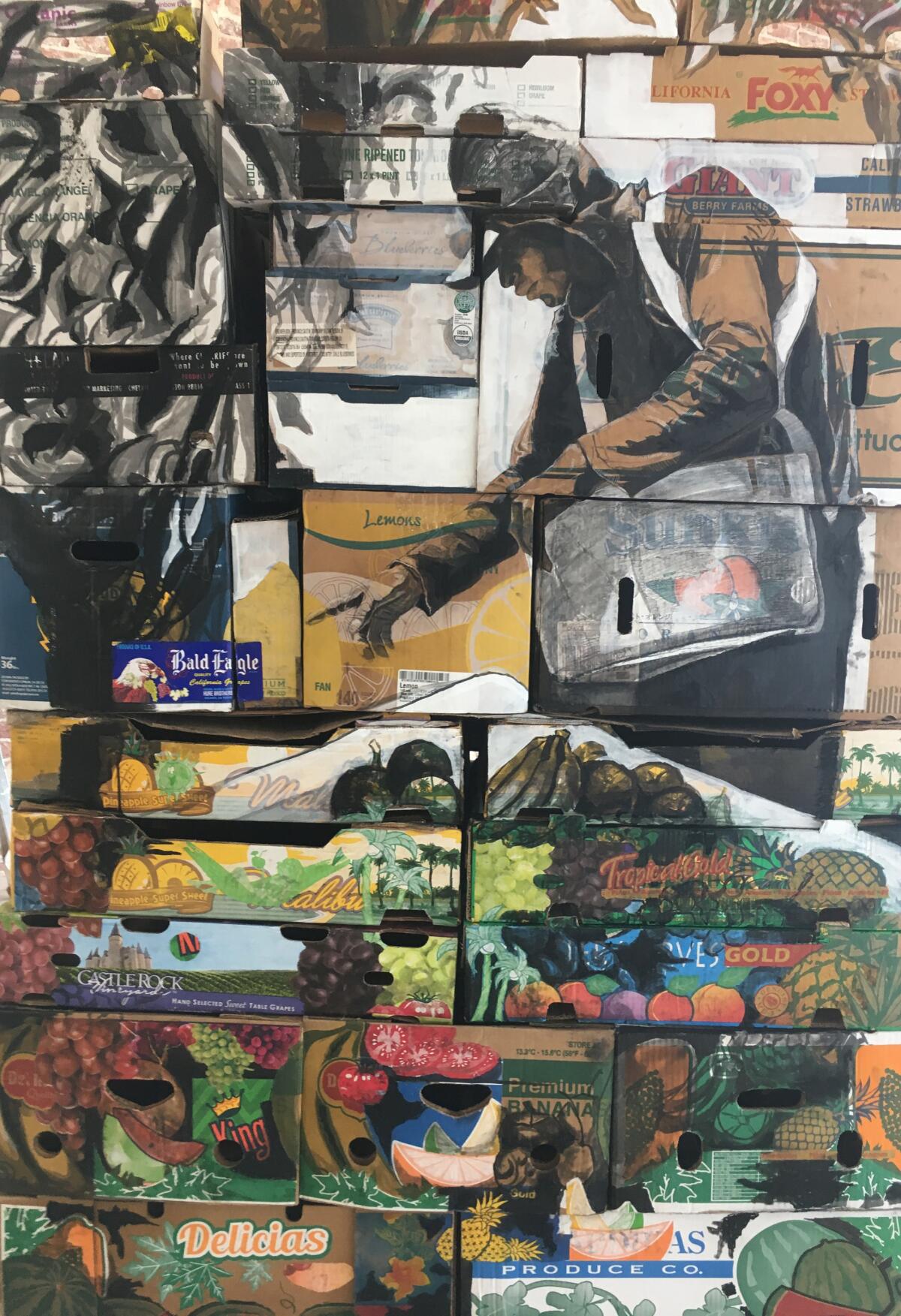

The stark white walls of the Long Beach Museum of Art Downtown are lined with color. Paintings depicting neighborhood landscapes and tropical fish hang on the perimeter, while glazed pottery sparkles center stage. But tucked away in a corner is perhaps the most vibrant piece of all — a tower of discarded cardboard boxes.

Used produce boxes are the medium of choice for Long Beach artist Narsiso Martinez. Drawing on his experience in the fields as a farmworker, Martinez, 41, etches the faces of his community above the glamorized fruits of their labor “to have a conversation between the farm workers and the agricultural industry.”

The 3-D project, “Friends in Freshness,” is on display through Nov. 3 at the newly reopened LBMA Downtown and will be featured at Saturday’s grand opening celebration.

“I wanted to represent their contribution,” Martinez said. “I feel like these individuals deserve fair treatment, fair opportunities as well. I worked for many years in the fields. … We exchanged stories. I heard their stories, and the struggle is real, and they are working really hard.”

While Martinez’s pieces have focused on farmworkers for several years, his artistic vision wasn’t always 20/20. He started like many creatives do, painting portraits of neighbors or celebrities in magazines — until his first art history class at Los Angeles City College exposed him to the works of Vincent van Gogh.

“I got inspired by seeing his peasant scenes, his agricultural landscapes, and I was like, ‘Damn, I want to paint stuff like this,’” Martinez said. “There’s this feeling of familiarity I had when I saw his paintings, and I felt like I wanted to do something like that.”

That’s when Martinez decided he wanted to study art, starting with his undergraduate education at Cal State Long Beach. But his first semester hit hard. Though school was his passion, it was also a crippling financial burden.

“I almost gave up on school,” he said. “I told my family, maybe I was not going to go anymore because it was too expensive.”

His family’s proposed solution would later become the impetus for his most personal artistic expression. In order to pay for classes during the academic year, Martinez spent his summers picking fruit in the fields of Washington orchards.

Growing up in Oaxaca, Mexico, Martinez was no stranger to field work. But joining his brothers and sister on the front picking lines of corporate America was a different beast. Sometimes he spent more than half a day hunched over in the summer sun, pulling asparagus from 1 a.m. to 3 p.m. for just cents per pound. If the lengths of each plant failed to match exactly what the orchards wanted, they would be discarded, the dead weight taken out of his paycheck.

“It was unfair, but at that time I didn’t know,” Martinez said. “I was just barely starting. I didn’t know. And I started questioning all these things.”

Some of Martinez’s co-workers would later become his subjects for “Friends in Freshness.” One side of his cardboard puzzle depicts a woman who, with her husband, came to “rescue” Martinez by lending her hands at the end of a 14-plus-hour workday. Her husband was later deported to Mexico, leaving her to raise her children on her own. Martinez remembers her as one of the fastest and hardest-working pickers he’s ever seen, “whether it was cherries, asparagus or apples.”

Hers is the kind of story Martinez wants to tell in order to combat dangerous rhetoric swirling around the working-class Latinx community in America.

“When the now-president was campaigning ... I remember all those negative comments about Latino people,” Martinez said. “I really wanted to show the contribution of the Latino people, of this particular group of workers, to the economy. And I was thinking, how can I do that?”

While gathering research for “Friends in Freshness,” Martinez strove to learn more about the American farmworking community and culture — a culture he once rejected for fear of living in the past. Up until graduate school at Cal State Long Beach, his education had taught him to “move forward,” and he sought to leave his Oaxacan roots behind.

But the more time he spent with his co-workers, the more he came to appreciate their way of life, surrendering himself to the familiar and somber sounds of Mexican corridos.

“I started to listen to the music they listen to and go to the kind of events that they go to,” Martinez said. “And so in that way, we’d kind of share stories, and those stories became part of the artwork ... I got to understand that it’s their identity. That’s what gives them a sense of unity.”

Going back and forth between the orchards and Cal State Long Beach, Martinez often found himself code-switching when interacting with farmworkers versus grad students. He wants his art, however, to translate to everyone — not just an elite crowd of art lovers. At one point in Martinez’s graduate education, some suggested he take a more abstract approach to his creations, zooming in on just the farmworkers’ skin. He went against their advice.

“It would have worked if I was going to be there to explain it or if I had written something that would say, ‘These crazy marks are pores from the skin of a farmworker,’” Martinez said. “But maybe if it was in English, the farmworkers wouldn’t be able to understand it. So for me it was really important that the farmworkers were included in the process.”

Now he hopes those who experience his piece can appreciate the American farmworking community as he did in his artistic and personal journey — and as the LBMA did when it first decided to take him on as a resident in 2018.

“There was a compelling story that went along with his pieces, and I really realized there’s a lot going on in there, and there were some cultural differences that I think, in the beginning, he was uncomfortable with, but it’s really wonderful the way he’s learned to speak about his life,” said Ronald Nelson, executive director of the LBMA. “Every image that he does, he knows the person, and he’s painted them for a reason.”

Through all the hurdles, Martinez never doubted his mission to shed light on farmworkers, a group that has long been invisible to those who benefit from them. At the freshly restored LBMA Downtown, they are visible to the California public, illuminated in charcoal.

“There’s already progress because we are acknowledging them, and we’re seeing them,” Martinez said. “Maybe when they go to the grocery store and think about it a little bit more … I think changes happen in little steps, and I hope that this is part of it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.