The ever-sprightly step of Monday Evening Concerts, full of surprises after 80 years

- Share via

Monday Evening Concerts, far and away the longest-running new music series anywhere and one that has played an important role not only in Los Angeles but in the history of 20th century music, just opened its season at Zipper Hall — its first after turning 80.

What was new in 1939, when the series began in a small studio designed by Rudolph Schindler above a modest house in Silver Lake with a then-rare all-Bartók program, is now old. But back then, what was old was also new. The purpose of the programming was to explore the unknown, and that included neglected early music, which at the time could have meant Bach’s “The Art of Fugue.”

So what’s a spry old-timer to do these days when new and early music are everywhere? Looks like plenty. Eighty, it turns out, is the new twentysomething. Just ask the audience that filled Zipper. As usual, it ranged from the fashionable young crowd that the classical world lusts after to new-music regulars and luminaries up the age ladder to the 96-year-old composer and percussionist William Kraft, who played in MEC performances of Boulez and Stravinsky premieres in the 1950s.

Led by percussionist Jonathan Hepfer, Monday Evening Concerts has had no problem bridging these generations with extremely challenging music. Monday’s program turned to big, demanding pieces by two composers working in Paris in the 1970s who were not on the fringes then but are now.

At one extreme, the heralded Greek composer-mathematician Iannis Xenakis wrote grippingly abstract instrumental music that skirted the edges of rhythmic possibility when he wasn’t exceeding them altogether in his electronic music. At the other extreme was Bernard Parmegiani, the all-but-forgotten French electronic-music whiz who had his hand (and his studio) in just about everything from experimental work to commercial projects and film. It was his musique concrète that was intended to class up Walerian Borowczyk’s raunchy cult exploitation classic “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Miss Osbourne.”

Both composers were near contemporaries and, on some level, fascinating hucksters. Xenakis’ complexities came out of inelegant math. His technical procedures were beyond understanding and perception of nearly all musicians and listeners, and many of his results could likely have been produced by torturing performers less. But the ferocity of the onetime Athenian freedom fighter created a dramatic intensity with an incomparable sonic visceral punch.

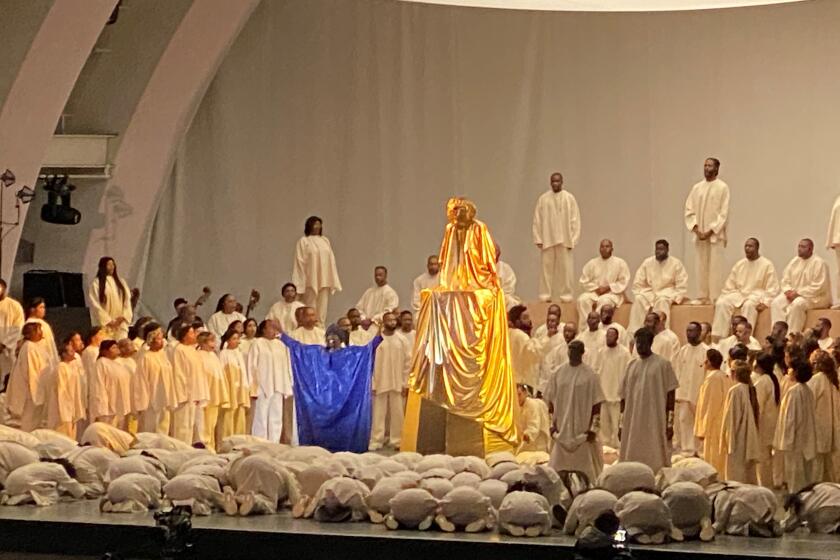

Kanye West packs the Bowl for “Nebuchadnezzar,” but the opera feels like a passion play or, worse, school production. Dare we wish for more Kanye-ness?

Ear plugs were handed out for the performance of Xenakis’ four-part, 45-minute percussion extravaganza, “Pléïades,” which had mallet instruments galore (including the deafening sixxen, consisting of irregularly tuned metal bars the composer invented) onstage on the side balconies, along with bass drum and many thundering timpani. But unlike so much loud music, the power of sound wasn’t meant to militantly take over your senses but to awaken you to them.

In contrast, Parmegiani’s “De Natura Sonorum” consisted of several short movements, each an electronic study in sound effects (a number of bits and pieces seemed good candidates for ring tones), fairly old-fashioned and certainly lightweight by 1975 Paris standards. They were given fanciful titles to help the listener along (such as “Pleines et Déliés” or “Thicks and Thins”) and proved mildly engrossing heard in booming surround sound. But the whole set wore, indeed, thin.

Hepfer’s idea was to mix it up with this odd composer couple, alternating movements of “Pléïades” and “Sonorum,” with the latter serving as something of an aural palate cleanser for the Xenakis onslaught. That may have meant missing the hoped-for perception-altering transcendence that Xenakis intended, but it added a curious new context for listening to both composers and to thinking about the various ways that music was breaking apart in the 1970s. It also gave the more-than-impressive dozen percussionists sweating blood a helpful break, to say nothing for a listener’s hearing. I’ve studied the score of “Pléïdes,” and I don’t know how these musicians do it.

But context happens to be, along with stunning performances of epic work, a big part of Hepfer’s MEC success. He previewed the season with Steve Reich’s 1971 “Drumming” at the Getty (which I missed) and Morton Feldman’s nearly five-hour 1984 “For Philip Guston” at the Hauser & Wirth gallery, where there is a Guston exhibition. Both of these American works take apart and rhythmically fraction minimal musical materials in exacting ways that feel more like fresh reinvention. Feldman’s trio (played by Hepfer, pianist Brendan Nguyen and flutist Christine Tavolacci) proved spellbinding. The audience was free to come and go, but most stayed put and listened as if not being able to help themselves. None of us wanted to miss anything, even though we knew we wouldn’t, so gradual the change.

Hepfer further framed Monday’s program by introducing it with a tribute to the late pianist Márta Kurtág: five, short piano duets that her husband, Hungarian composer György Kurtág, wrote for them. Each was an exquisite arrangement of music from the 14th to 18th centuries, just the kind of thing MEC once heralded. They were luminously played by Gloria Cheng and Vicki Ray, two well-known members of the Piano Spheres series founded by their mentor, Leonard Stein, who just happened to have been one of the original MEC figures.

Still, it was the ground-shaking-under-your-feet, air-vibrating-inside-your-brain “Pléïades,” no matter the composer’s hocus pocus, that delivered the irrepressible shock of the new. Within Xenakis’ astonishing resonances were the seeming source of the 80-year-old Monday Evening Concerts’ fountain of youth.

Opera UCLA premieres Carla Lucero’s “Juana,” based on the fascinating life of proto-feminist nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.