Judson Studios, oldest family-run stained-glass maker in the U.S., weathers the storm

- Share via

Tucked away in a rambling, two-story, shingle-and-stone structure in Highland Park lies the 123-year-old Judson Studios, purported to be the oldest family-owned and family-run stained-glass studio in America.

The work of Judson artisans graces Frank Lloyd Wright’s historic Ennis and Hollyhock houses in Los Angeles, the glorious 1932 First Congregational Church of L.A. and the magnificently restored octagonal Wilshire Boulevard Temple, not to mention hundreds of other houses of worship across the nation. Judson’s window for the Church of the Resurrection in Leawood, Kan., the largest United Methodist congregation in the nation, has nearly enough stained glass to cover a basketball court.

Judson has endured two world wars, the Great Depression, 9/11 and the Great Recession of 2008. For David Judson, the fifth-generation family member who runs the operation, survival of all that adversity in the past provides some encouragement for Judson Studios’ present: For the first time in its history, Judson Studios had to lay off the entire staff — all 23 designers, fabricators, installers, artists and painters — so they could apply for unemployment following the coronavirus-related stay-at-home orders.

Judson said he hopes to get his people back to work as soon as it’s safe to return to the studio and projects can move forward again. The temporary closure came just as the studio was poised to celebrate a new book, “Judson: Innovation in Stained Glass” by Judson and Steffie Nelson, which chronicles the artists, architects and craftspeople who have created so much artistry over more than a century.

In 1897 William Lees Judson, a plein-air painter who had moved from Manchester, England, to L.A. for health reasons, launched the Colonial Art Glass Co. in downtown L.A. He also founded the Los Angeles College of Fine Arts, an important player in California’s Arts and Crafts movement and eventually part of USC. The school operated in a Highland Park building that was reconstructed in 1911 after fire and now is on the National Register of Historic Places.

William Judson retired in 1920, the school moved to USC’s main campus, and the glass company — renamed Judson Studios — took over the Highland Park building. Most of the business that followed was ecclesiastical, projects such as All Saints Church in Pasadena, where Judson glass is installed alongside Tiffany windows in a century-old landmark, and St. James Episcopal Church in Koreatown, where traditional stained glass from 1932 later was joined by a design incorporating the image of Cesar Chavez.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

When the lead that is so integral to the studio’s work became unavailable during World War II, business slowed considerably. But after 1945 the construction of war memorials spurred demand for stained glass. So did the popularity of neo-Gothic churches. Judson Studios thrived.

When hard times came again in 1971 in the form of the 6.5-magnitude Sylmar earthquake, which destroyed Glendale Presbyterian, Judson Studios salvaged glass scenes so they could be reinstalled in a new chapel.

After the 1994 Northridge earthquake, Judson Studios helped churches across the region pick up the pieces — sometimes reconstructing broken window designs using old photographs or drawings.

David Judson said the company largely used the same methods for decades, working with outside artists to emulate the late 19th century Munich School style and planning out projects using full-size watercolor renderings created by hand.

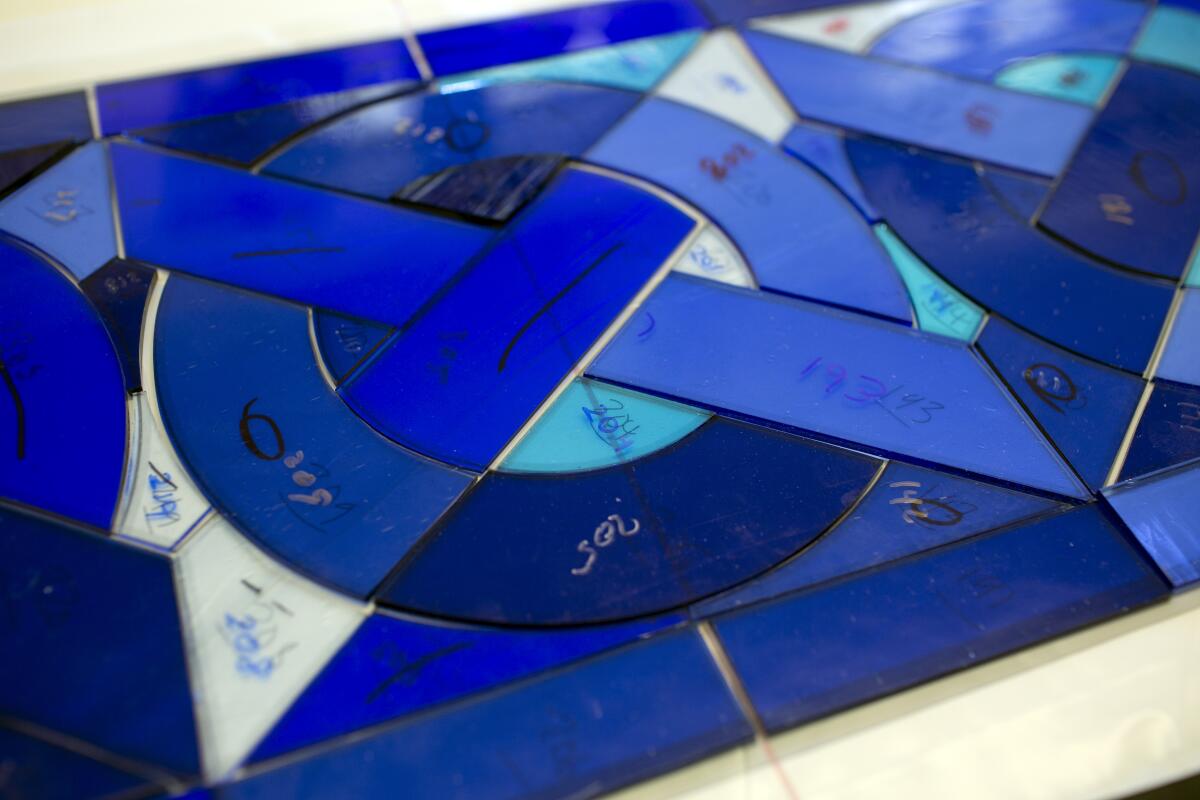

In the early 2000s, the company started employing its own designers and artists in the studio, designing windows on computers. It began expanding into fused glass, where multiple pieces are joined in a kiln without lead borders, and into faceted glass, where pieces are held together by epoxy.

The 2008 recession led Judson to diversify the company and rely less on churches. Judson artist-in-residence Sarah Cain recently revealed her first major public work: a 150-foot-long stained-glass installation at San Francisco International Airport. Street artist and designer David Flores also collaborated with the studio, incorporating fused and leaded glass with silkscreened enamels for a 7-by-3-foot portrait, “The Muralist.”

But as the new book documents, Judson Studios has not abandoned its work in religious spaces. The Church of the Resurrection project required 160 panels that took three years to complete at a cost of $3.4 million — a project so large that Judson built a second studio in South Pasadena to finish the work.

Judson’s monumental projects include the restoration of the windows at the Air Force Academy Cadet Chapel in Colorado Springs, Colo., a deconstructed Gothic cathedral with soaring spires that evoke a fleet of fighter jets poised for takeoff.

The chapel is 120 feet tall with windows that span that entire height. Completed in 1963 by Horace Judson, David’s grandfather, the glass is being pulled out and the chapel disassembled — a reconstruction project aimed at fixing water leakage.

The Judson windows incorporate 24,384 pieces of faceted glass in a rainbow of colors. The $158-million project will take three to four years to complete.

Saul Shaw has been working at Judson Studios for 10 years, first as the lead cutter. He scored glass with a tungsten tool and then finished breaking the fragments with his hands. Now he’s director of operations, fully cognizant of all the people around the world waiting for Judson to restart operations.

“Construction is classified as essential, but making the windows is not,” said Shaw, who apprenticed in Britain before moving to the States. “Back in England, all the churches are already built, so all the work is restoration. Here, every day is different. We’re not cookie-cutter at all.”

When asked what he missed most, Shaw answered almost instantly.

“I miss being busy,” he said. “I go to work and the day’s over before you know it.” He and his coworkers take pride in their jobs. Now they’re just hanging around waiting to start again, though he’s quick to acknowledge that at least they have customers willing to wait for them.

“We’re one of the fortunate trades,” he said. “In the long run we’ll be fine.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.