After the withdrawal, U.S. museums need to tell a richer story about Afghanistan

- Share via

Over the years, the U.S. public has shown little appetite for the war in Afghanistan. The same could be said for the country’s cultural institutions. We have been at war with and occupied Afghanistan for two decades, yet culturally it has been a blip.

“It takes a lot of convincing to make anyone want to do shows about it,” says Muheb Esmat, an Afghan independent curator based in New York City. “This war has been going on for a long time, but we only get into it when it’s a catastrophe.”

Afghanistan’s best and brightest are leaving the country in droves, taking with them skills and knowledge that the Taliban wants put to its service.

A year ago, Esmat organized “No End in Sight,” the first U.S. solo show of work by Afghan artist Aziz Hazara, who is based in Berlin. Staged at the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College in New York’s Hudson Valley, the works examined the ways in which media and technology — such as omnipresent night vision technology — have shaped the way we have viewed the war in Afghanistan.

Early last year, Hazara was also the subject of an installation at the 22nd Biennale of Sydney in Australia. For that show, he presented a multichannel video installation titled “Bow Echo,” which shows five Afghan boys struggling to stand atop a windy peak as they play notes of warning on a plastic bugle. The piercing cries of the bugle, along with the ways in which the boys struggle mightily with the unseen force of the wind, are full of poignance and futility.

The Biennale, however, was shut down a little more than a week after it opened due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thankfully, aspects of Hazara’s installation can be viewed online courtesy of the Google Arts & Culture initiative.

The U.S. military occupation of Afghanistan may have officially ended with Monday’s departure of the last U.S. evacuation plane from Kabul, but the cultural ramifications of the conflict will be felt for decades. How they will reverberate in the West remains to be seen — particularly in the U.S., where Afghan cultural representation has generally been sparse or, in some cases, remains focused on the ancient.

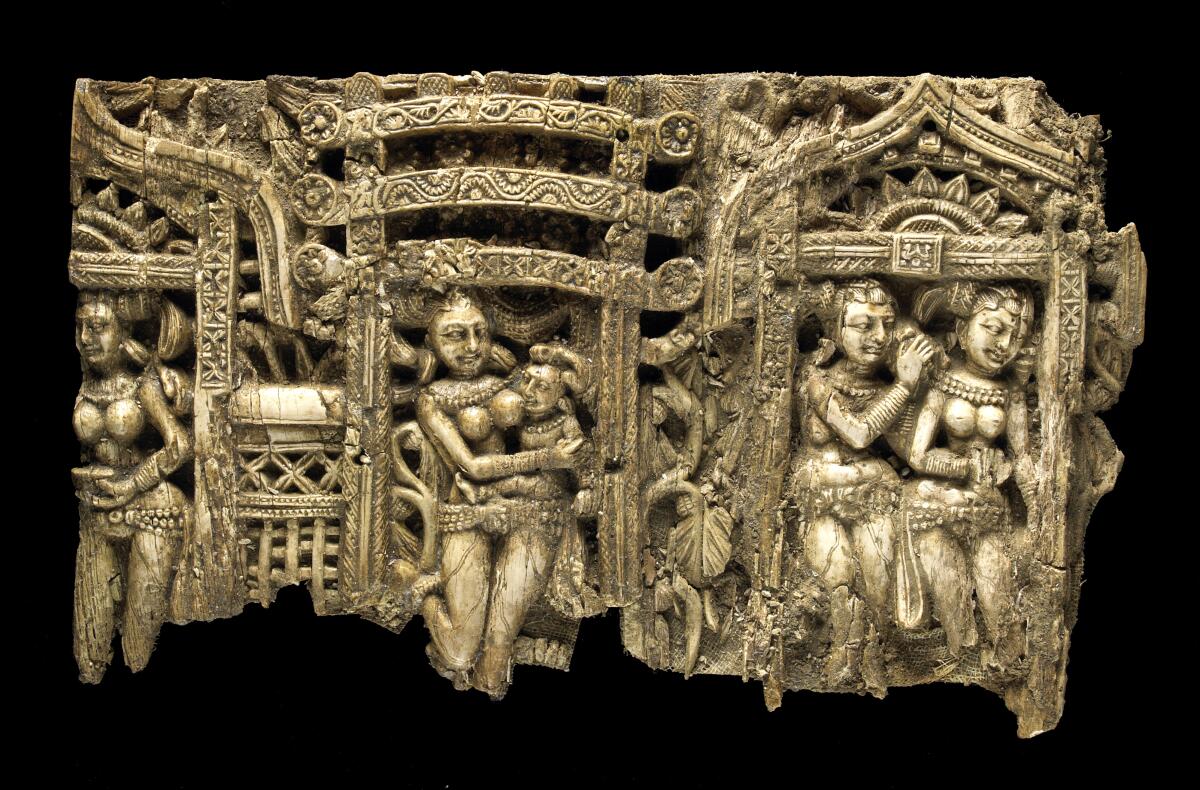

The biggest exhibition of Afghan art to be held in U.S. was perhaps the traveling show “Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures From the National Museum, Kabul,” which landed at various institutions in 2008 and 2009, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. It featured an estimated 200 ancient objects from the pre-Islamic era that illustrated the region’s strategic position as a Silk Road hub, a place where Persian, Greek, Mesopotamian and Indian cultures met and mingled.

Not only had these artifacts survived the centuries, they had made it through a particularly turbulent period of invasion and war at the end of the 20th century — stashed away by prescient curators around the time of the Soviet invasion in 1979 and unearthed in 2004 after the Taliban’s fall. Roberta Smith in the New York Times described these pieces as “triumphant” — a reminder that “every survivor saves much more than just itself: long strands of culture and identity and history waiting to be woven back together.”

More contemporary visions of Afghanistan by Afghan artists, however, have been harder to come by. Often, exhibitions staged in connection with Afghanistan feature photography by Western artists and journalists. There also appears to be a preoccupation with skateboarding girls. (The soft power of shredding.)

In the world of contemporary art, in fact, Afghanistan is generally registered through the eyes of Western artists — mostly famously, Italian artist Alighiero e Boetti, who in the 1970s became enamored of Kabul and opened the One Hotel, a guesthouse that became a gathering spot for itinerant artists and critics. It was there that he conceived his “Mappa” series, maps that question the subjectivity of maps and were presented in the form of an embroidered Afghan rug. Boetti would commission Afghan weavers to make the works, which would often takes years to complete. (One of these resides in the permanent collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.)

When documenta, the quinquennial organized out of Kassel, Germany, chose Kabul as a satellite location for the 13th edition of the show in 2012, Mexican artist Mario García Torres highlighted Boetti’s legacy in his own installation. Torres, who has a long-running dialogue with Boetti’s work, went to Kabul to find the location of the famous hotel and staged an imagined fax correspondence with the long-dead Boetti about the film he wanted to make about it.

Afghanistan’s rich cultural legacies are under siege. It’s time for Western arts organizations to step up to support them.

It’s a charming rabbit hole. It also provides a limited view of art in Afghanistan.

“Everyone [in the West] who thinks of Kabul thinks of Boetti and his hotel,” says Esmat. “They trace his history back, but they couldn’t trace it back to the artists who are already there at the time that Boetti was traveling to Afghanistan.”

Boetti has received copious institutional treatment; the representation of work by contemporary and 20th century Afghan artists, not so much.

A show of video art from Afghanistan and Iran titled “Sight Unseen,” featuring work by artist and educator Rahraw Omarzad, appeared at New York’s Asia Society in 2009. In 2016, the Hammer Museum hosted Afghan street artist Shamsia Hassani for a residency. Last year, artist Mariam Ghani (who happens to be the daughter of deposed Afghan President Ashraf Ghani) presented work from her project “What We Left Unfinished” at the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston. Among other works, it included a documentary of the same name that looks at the stories of five films from Afghanistan’s communist era that were left unfinished. (It was released in the U.S. last month.)

Lida Abdul is one of the better known Afghan artists to emerge in the Western art scene. Born in Kabul, she and her family fled Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion. She ultimately relocated to Los Angeles, where she received a pair of bachelor’s degrees from Cal State Fullerton (in philosophy and political science) and a master’s in fine art from UC Irvine.

The last U.S. forces flew out of Kabul’s airport in Afghanistan, the Pentagon said Monday, bringing down the curtain on America’s longest war.

She has had solo exhibitions at the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2008 and the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois in 2010. And she represented Afghanistan at the 51st Venice Biennale in 2005 — the one and only time the country has had a national pavilion in the exhibition. On that occasion, she presented the video work “White House,” which shows the artist painting the rubble of the former presidential palace in Kabul a bright shade of white. The piece was later acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Late next month, her work will be featured alongside that of high-profile U.S. artists such as Joan Jonas and Lawrence Weiner in the inaugural exhibition of ZACentrale, a new three-year project space in Palermo, Italy, run by the Fondazione Merz.

Despite living in the U.S., Abdul’s CV shows that she has exhibited more extensively abroad than she has here. And while she has appeared in various Los Angeles group shows, including several exhibitions at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions early on in her career, she has yet to land a solo museum exhibition in L.A. Not even a project space.

“No one has taken any interest,” says independent curator Sara Raza, who has worked extensively with Abdul for almost two decades, most recently featuring her work in a group exhibition at New York’s Rubin Museum titled “Clapping With Stones: Art and Acts of Resistance.” “They take interest only once there is a disaster.”

And when institutions do take an interest, the narratives presented can reinforce preexisting notions about Afghanistan — often dwelling on gender and conflict at the expense of everything else.

Gazelle Samizay is an artist who was born in Afghanistan and now is based in San Francisco. Her video work “Upon My Daughter,” from 2010, can be found in the permanent collection at LACMA. In 2019, she co-curated, with Helena Zeweri, the group exhibition “Fragmented Futures: Afghanistan 100 Years Later,” held at the Brand Library in Glendale — one of the rare group shows in the U.S. devoted exclusively to the Afghan experience.

“I think [institutions] should be self-reflective about what kinds of narratives they are accustomed to, the Orientalist narratives of the oppressed Afghan woman who is both submissive and exotic,” she says. “Those kinds of images and artworks sell really well in the West, but they are really harmful because they portray Afghan women in a really simplistic way that doesn’t acknowledge their agency.”

Esmat concurs. “There are different narratives and the art world needs to be supportive of that,” he says. “We need to take a wider look at the whole place.”

Afghanistan, says Raza, “has a very unique cultural topography, both in terms of climate and environment, but also its politics. It’s diverse. It’s multiethnic. It’s important to say that.”

Khadim Ali is an Afghan artist of Hazara origin who is now based in Australia. The Hazara have been persecuted by the Taliban and Ali was therefore born in Pakistan. His work draws from classical traditions (the painting of miniatures and epic poetry) but also more conceptual forms (he has created sound installations employing Taliban propaganda CDs). His paintings were shown as part of documenta 13’s presentation in Kabul and are held in the permanent collection of the Guggenheim Museum. Last year, he had an exhibition at New York’s Aicon Gallery.

You can help Afghan refugees by donating money to or volunteering with organizations in California.

Ali’s story is more complicated than the picture generally presented in the West, and his art represents that. This spring, in an interview with Ocula Magazine, he noted that the Taliban “are children of the West.”

“The were created by Westerners in Afghanistan to fight the Soviets at that time. And then after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, these terrorist organizations were left with no exit plan.”

For two decades, the U.S. and Afghanistan have been inextricably linked. But, in so many ways, our museums have failed to examine that. The withdrawal marks a moment in which to take a look.

“Tell the complicated story,” says Samizay. It’s the least we can do.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.