At Regen Projects, Abraham Cruzvillegas breaks the rules, including his own

- Share via

A guy walks into a bar.

No, a guy walks into a gallery, carrying a bar — a wooden dowel painted in bright stripes of color. Throughout the 1970s, Romanian artist André Cadere stalked parties, openings and the streets of Paris with his Barres des bois rond (round wooden bars), often placing them in other artists’ exhibitions, a louche gesture of interference but also one of expansion, keeping the work suspended between object and performance.

“The segments had patterns,” artist Abraham Cruzvillegas explained at the opening of his latest exhibition, “Tres Sonetos,” at Regen Projects. “Let’s say, red yellow blue purple, red yellow blue purple — green — red yellow blue purple. He was intentionally breaking his own rule. That was the system.”

Peripatetic by dint of exhibitions and residencies throughout Europe and South America — he has taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris since 2018 — Cruzvillegas is anchored to Mexico City as a site of familial roots and the birth of his artistic guideposts. Since 2007, he has been associated with a system of his own making called autoconstrucción, inspired by the communal, ad hoc methods of construction in the Ajusco area south of Mexico City, where his parents live and where the homes often are built in response to the material and social conditions of local families.

The newly expanded Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego is a revelation, with an impressive permanent collection and a sharp Niki de Saint Phalle show.

A new baby means a new room is added to the back. Neighbors pool resources and expertise to literally build one another up. Sections of rebar or exposed pipe extend from the sides of buildings, signifying readiness for expansion. Nimbleness, improvisation and working with materials at hand are cardinal features of this concept that Cruzvillegas carries with him in the spiritual home of his practice.

Visitors may come to “Tres Sonetos” with a reductive version of autoconstrucción, knowing that Cruzvillegas constructs most of his works on site, making the act of creation and installation one and the same, and creating an expectation for architectural elements from around Los Angeles. But the works are simply nothing like Cruzvillegas has made before.

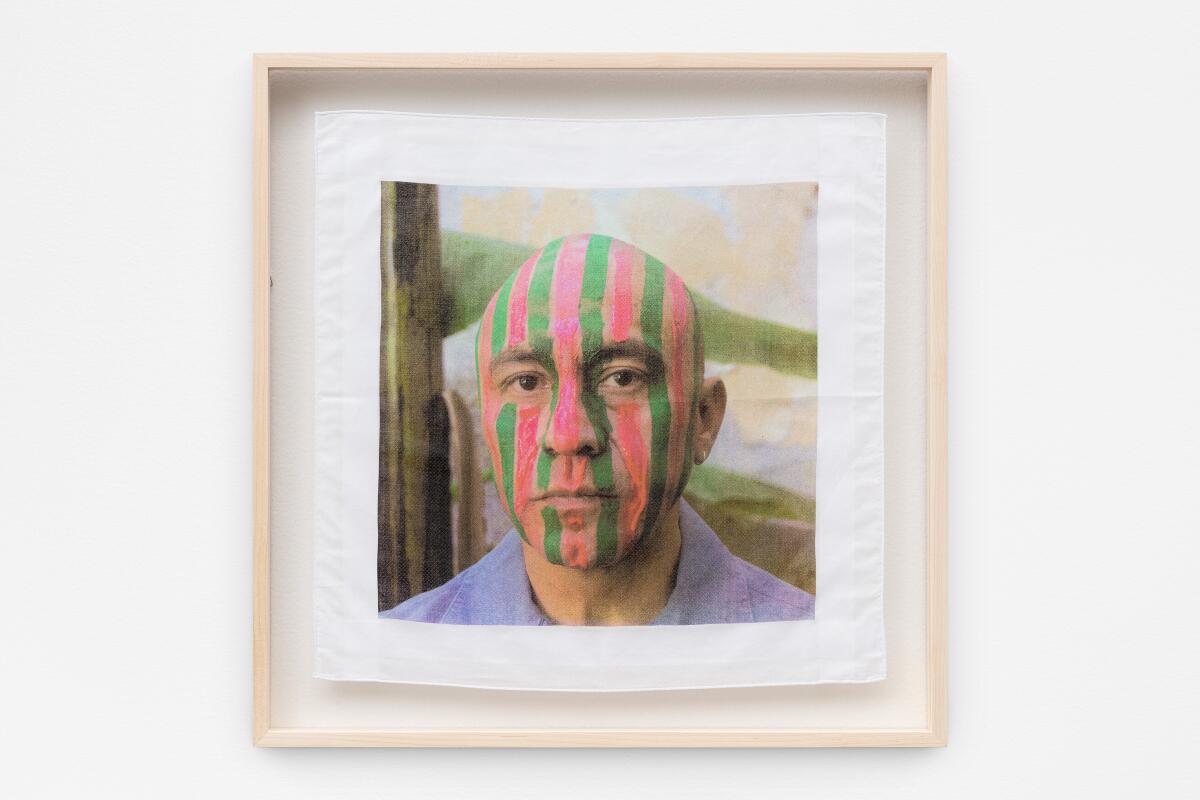

There are three major elements — large abstract paintings, small photo-based works and bright geometric sculptures — and each type of work is made up of threes. Three primary colors, three abstract shapes melded into one. The paintings and sculptures, with their gestural strokes and sleek geometry, respectively, have the look of more straightforward modernist works. But there is a game happening, and the more acquainted you get with the work, the more the game starts to complicate, or fail, or collapse on itself.

“The idea gravitates around the rhythm and the structure of a poem by Concha Urquiza titled ‘Tres Sonetos,’” Cruzvillegas said. “I wanted to do something completely different but still anchored in my previous practice, and in language. I’ve been dealing with the idea of autoconstrucción as evidence of the instability of identity — the construction of the self.”

Like Cadere’s bars, the sculptures are bright and geometric at first glance, but close up they are more rough and inviting. Visitors are welcome to sit and stand on them, turning them into plinths, or sites of performance. Each sculpture also has a hole on one side, to be played as a percussive instrument.

During the opening night performance, Cruzvillegas stalked the gallery space, playing rhythms on a painted turtle shell hung around his neck, using antlers as drumsticks, and ending with a reading of Urquiza’s “Tres Sonetos” aloud, his shoes scuffing the sculptures, almost as a mark of invitation.

Play is the substrate of autoconstrucción and its driving force, even as Cruzvillegas alternately breaks up and buttresses the idea with a catholic range of historical and artistic touchpoints, interests and memories.

“It’s trying to create some sort of game,” he said. “Rules for making a new project. The rules can lead me to new places, new things to research, and in the end they take some sort of shape in space. This new project is following rules that I created for myself, a game of producing questions. At some point, something from within breaks the rule of the game.” We do love an exception.

In 1986, Cruzvillegas attended a talk by the writer Carlos Monsiváis and learned about the Mexican Modernist group Los Contemporáneos, who published a literary magazine of the same name. In the wake of the Mexican revolution they resisted the politics of homogenous national identity.

“I prefer dealing with unstable identity,” Cruzvillegas said, “and in that way, in that moment, I identified with them.” Eager to know more, he asked Monsiváis who his favorite writer from the group is. “He said, Forget about all the rest, you have to read Concha Urquiza.’ It was a beautiful discovery for me because she was different even from the whole group.”

Urquiza was a Catholic and communist, eventually breaking with the latter. She wrote structured, classical verse at a time when her contemporaries were uniformly breaking form. “I’ve been in love with her poetry since 1986. I’ve been wondering for so long, how to materialize her poetry in my work,” Cruzvillegas said. “I’m trying.”

Cruzvillegas ended the performance at Regen by nailing the turtle shell to a section of unfinished drywall that is also part of the exhibition — a nod to the material origins of autoconstrucción, though Cruzvillegas noted, “Literally, I’m trying to give flesh to her poetry. I’m talking about language, not this” — he waves his hand over the exhibition — “it’s language.”

Somewhere between the object and the idea, word did indeed become flesh, and it became briefly clear that the object of Cruzvillegas’ game, the paradox of artists making rules, is in service of expansion.

“It’s very important for me to face myself in a political way that is not literal or didactic or even narrative. To construct something that can produce questions,” he said. “In a society like ours, that is so unequal, unfair, violent, et cetera. What is my thing in this, if not producing questions that help us, as humans, to see reality in a different way?”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.