Artist and curator Hideo Sakata, a force in the Los Angeles arts community, dies at 87

- Share via

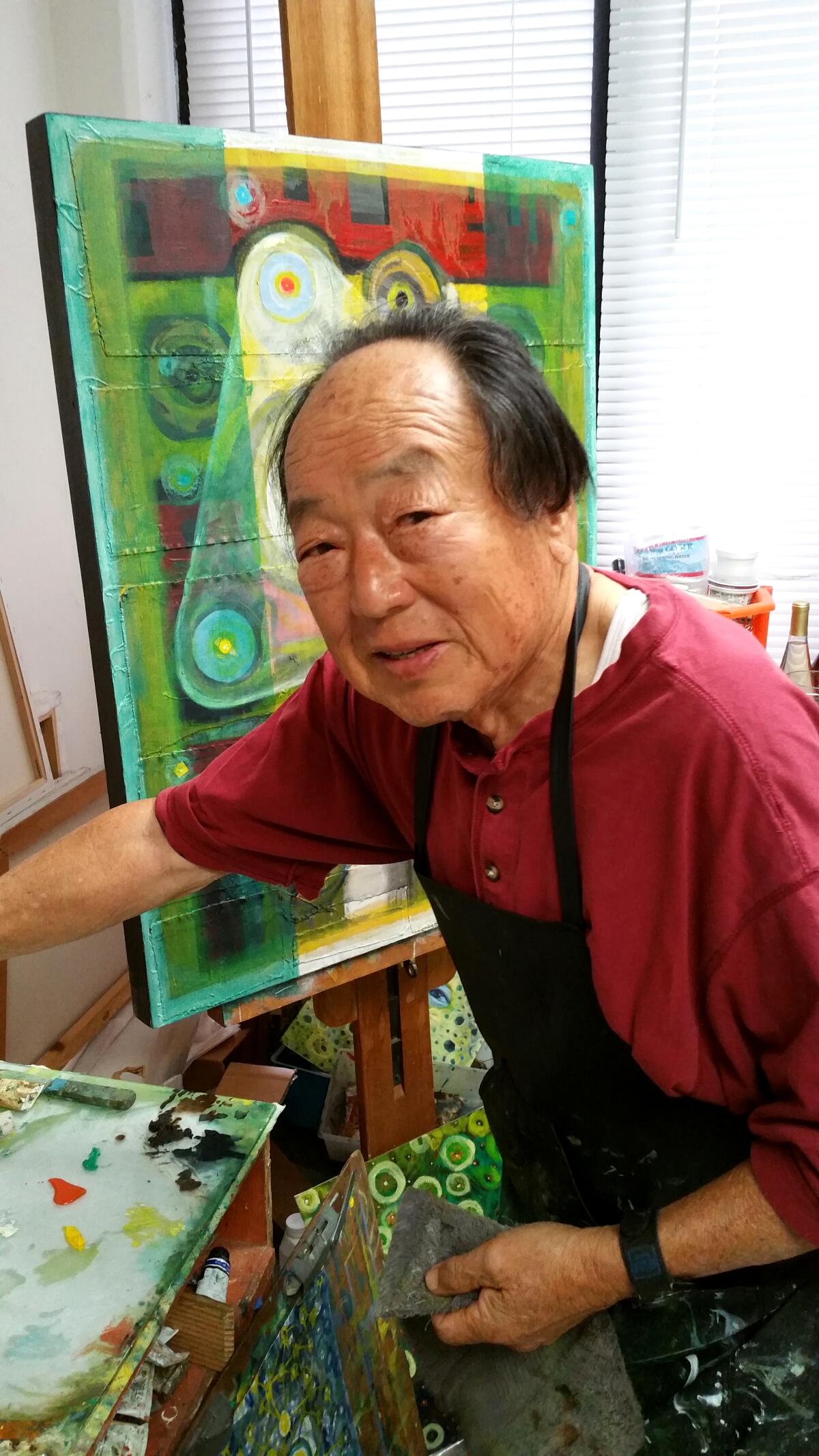

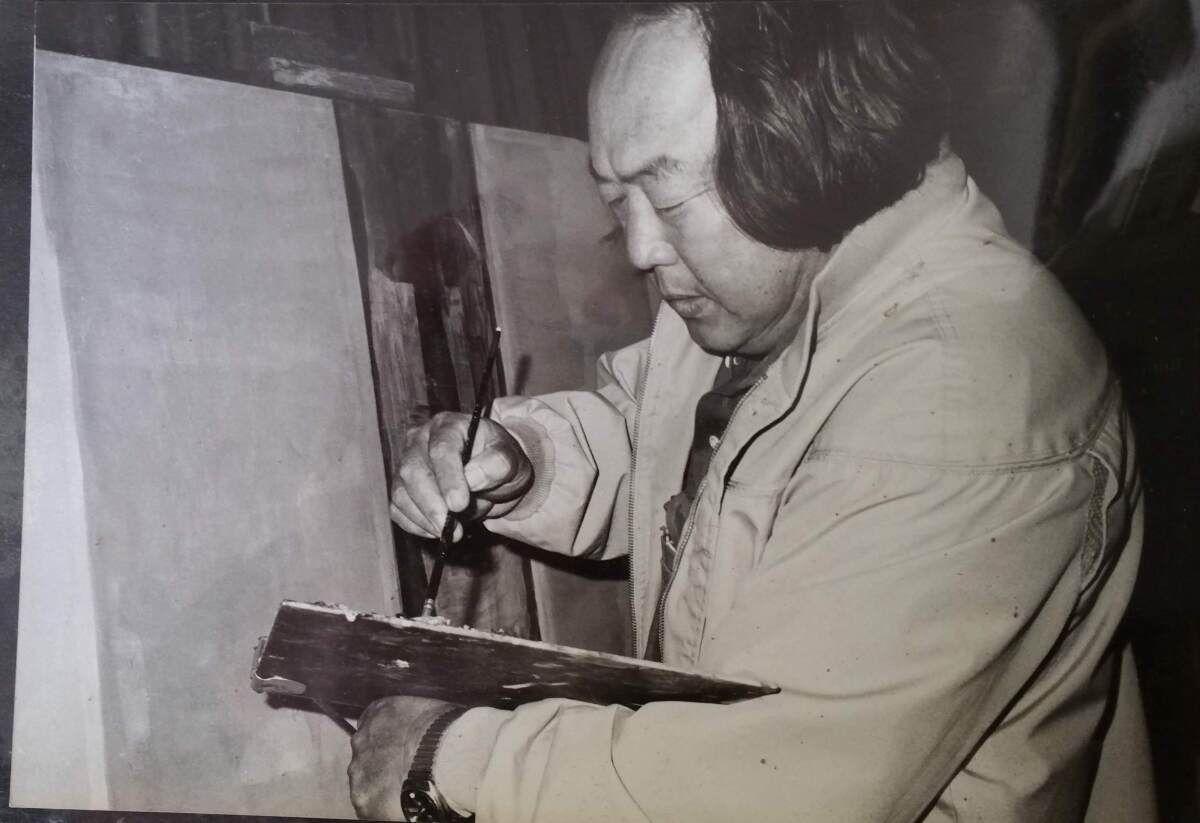

Hideo Sakata, the Nagasaki-born, Los Angeles-based artist and curator, died July 30 after a lengthy battle with cancer. He was 87 years old.

A hibakusha, or atomic bomb survivor, Sakata was a not quite 10-year-old child playing in his family’s garden when the United States bombed his hometown on Aug. 9, 1945, three days after the bombing of Hiroshima. This childhood experience of the horrors of war would fuel his lifelong commitment to fostering intercultural understanding through art. Though sick for the last five years, Sakata-san, as he was affectionately called by his friends and collaborators, continued to paint daily and organize exhibitions.

Last week, the Nagasaki Prefectural Museum opened its 44th annual exhibition held on the anniversary of the bombing. For over four decades, Sakata collaborated with the museum to bring together artists from his intersecting networks of diasporic artists in Los Angeles and beyond. The exhibition, “A Bridge for Peace,” exemplifies Sakata’s unwavering conviction that art can reflect the best of our shared humanity and thus act as a potent counterpoint to the worst, which he witnessed firsthand. In his own words: “Peace is at the essence of everything I do.”

Sakata arrived in Los Angeles in 1970 from Mexico, where he first intended to live and work after leaving Japan in 1967. Artists from the so-called Pacific Rim were among the many immigrants to Los Angeles in the late 20th century, at once mingling with and distinct from both the longstanding Asian diasporic communities and mainstream art scene. Sakata was among the many artists of color who struggled to find footing in the city’s white, male-dominated, commercial art scene but gradually formed their own networks, meeting through art schools, self-organized exhibitions and other social events.

Gregarious and energetic, Sakata would prove to be a sustaining force for many of these networks. One such group would meet to discuss their practices and careers, often at the Koreatown studio of Japanese American artist Matsumi “Mike” Kanemitsu. These meetings eventually lead to Sakata’s founding of Lantern of the East Los Angeles in the late 1980s, with artists Lee Kye Song, P. Khemraj and Yoko Kamijyo, who saw Eastern aesthetic sensibilities as an important counterforce to the Western-dominated tendencies of contemporary art. LELA sought to create opportunities for encounters with art practices that reflected the diversity of Los Angeles and flows of culture in a globalizing world.

In 1996, LELA organized its first international art exhibit in Pyeongtaek, South Korea. There were 46 artists representing South Korea, Japan, the United States, India and China. These art festivals continued yearly, with the 2002 iteration in Los Angeles at the Angels Gate Cultural Center, the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center, and Cal State Los Angeles bringing together 126 artists from 46 countries. With his tenacious ingenuity, Sakata was the driving force behind these endeavors and the only one of the original four artists to continue with the organization, which eventually became a 501(c)(3) nonprofit.

Another lasting initiative was the “art camps” that brought artists to various countries for extended periods to collaborate with local artists, culminating in an exhibition. The first was hosted by the Hong Kong-born artist Diana Shui-lu Wong on her property in the Santa Monica Mountains and others took place in Thailand, Japan and elsewhere. These self-organized residencies were first supported by members of his community and later by both government and private entities.

Sakata’s decades of making art and community were fueled by his unwavering belief that art can play a vital role in fostering peace. His friend and LELA artist Nancy Uyemura said, “Art was the bridge that would bring people together and Sakata did so much to facilitate that dream. We will miss his energy and passion for life, art and community. We remember his creativity, his strength and his endless search for ways to bring peace to the world.”

In his abstract paintings, he often returned to the image of the atomic bomb, through a recurring motif of an orb hovering in a vertical band of color. The art critic and curator Peter Frank, a longtime supporter, analyzed these evocative compositions through Sakata’s capacity to transform trauma into enduring creative energy. He described the vast spaces surrounding the orb and bands as “regions of metaphysical portent … the realm of gross human experience, and that infernal concussion only a single event.” Sakata was included in the 2022 exhibition “Abstract Los Angeles: Four Generations” at the Brand Library and Art Center, alongside Peter Alexander, Billy Al Bengston, Ed Moses, Andy Moses and Margaret Nielsen, among others.

However, like so many artists of color of his generation, Sakata did not experience the mainstream success of his white contemporaries, like Sam Francis, a friend, not even late in life. (That was the case for artist Kenzi Shiokava, who participated in many LELA events.) Sakata’s exhibition history is peppered with titles such as “West Meets East,” “Multi-Cultural Exhibit of Los Angeles” and “Exhibition of Asian Pacific American Artists.” Though he lived for more than half a century in Los Angeles, his institutional exhibits — as an artist or curator — largely took place in Asia.

The estate of Kenzi Shiokava, who died in 2021, is being represented by Hollywood gallery Nonaka-Hill. A new retrospective on view now celebrates his monumental work.

Still, his exhibits at L.A. Artcore and the JACCC in Little Tokyo, or the M.M. Shinno Gallery in Mid-City, are glimpses of an Asian American L.A. art history. In tracing his movements across the city, to Korea, the Philippines and back, we can find ways in which Asian and other diasporic artists in Los Angeles created their own spaces, platforms and systems of support. Wong recalled their “great friendship” and his gift for initiating gatherings that brought pleasure to the struggle of being artists. Frank remembers Sakata as “very special, indomitable, generous to a fault.”

In a video interview conducted during the last months of his life, Sakata said, “The time of my death is determined without my knowledge, so if I paint diligently until then, I can say ‘thank you’ when the time comes.”

In addition to his community, Sakata is survived by his wife, daughter and three sons. According to LELA, a memorial will take place in September in Los Angeles.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.