Review: Robert Wilson finds the poetry in ‘Lecture on Nothing’

- Share via

“Lecture on Nothing,” which is published in John Cage’s “Silence,” is a classic, studied and often recited. One of its much-quoted lines is “I have nothing to say and I am saying and that is poetry as I need it.” The conductor Robert Spano read the lecture at the 2006 Ojai Festival, as the director Peter Sellars once did at the Salzburg Festival, slowly savoring every instant.

But what Cage called a composed lecture didn’t always go down so easily. The composer first delivered the 40-minute lecture — which is structured like a piece of music, with pauses and repetitions — at the painter Robert Motherwell’s 8th St. Artist’s Club in Manhattan in 1950. After hearing the line “if anyone is sleepy, let him go to sleep” repeated more than a dozen times, a member of the club stood up and screamed as she walked out, “John, I dearly love you, but I can’t bear another minute.”

Robert Wilson, in his theatrical production of “Lecture on Nothing” — which was commissioned for a German celebration of the Cage centenary last summer and given its U.S. premiere Tuesday night in Royce Hall by the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA — goes far further. Wilson’s once revolutionary 1976 operatic collaboration with Philip Glass, “Einstein on the Beach” — just concluded at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion — is itself now a classic, and the director in this new Cage production reminds of where he came from and why.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

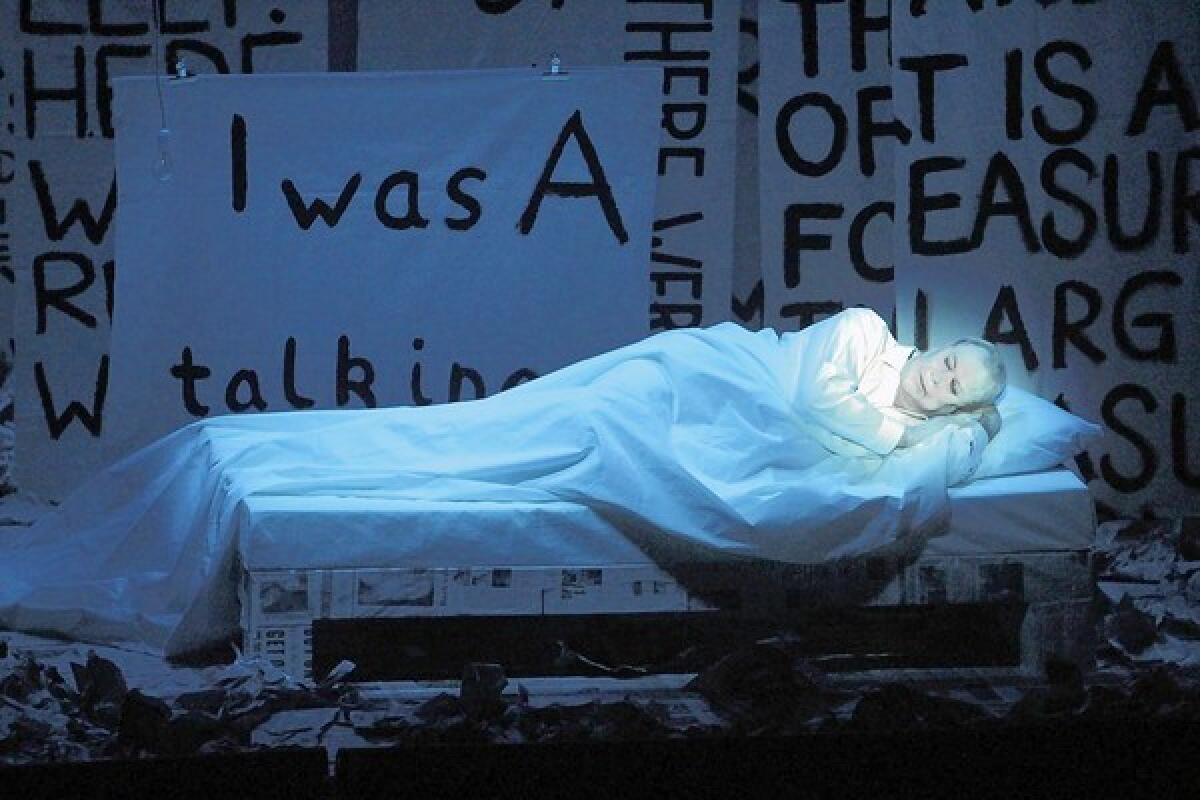

A one-man show, this “Lecture” began with Wilson, dressed in white and covered in white body paint, seated at a table and motionless as a statue. The stage was littered with crumpled newsprint and backed with banners that have collage-like fragments of Cage’s text. A piercingly loud, complex electronic sound blared for an unbearable seven minutes, as if attempting to re-create in the audience the response Cage got at the Artist’s Club. It was a sound not unlike what you experience when you are given an MRI. It may be awful, but it can also be enjoyable if, deep down, you know it’s for your own good.

Then came blissful silence. “What we require is silence; but what silence requires is that I go on talking,” Wilson read, as he began Cage’s text while moving his fingers across sheets of paper. After that theater-of-cruelty electronic blast, we were now in the right place. As is typical of Wilson, his movements were very slow, his painterly touch was seen on every inch of the stage and the lighting was so exquisite that it created a magnificent world of its own.

Cage’s text is charming, often amusing, often quotable, equally often intentionally infuriating and profoundly thought provoking. The composer was in a period of transition, moving away from somewhat traditional composition to the making of music that incorporated chance elements and that treated silence with devout respect.

CHEATSHEET: Fall arts preview 2013

The subject matter is the meaning of structure, form, method and material. Cage called it a composed talk and likened it to a glass of milk. “We need the glass and we need the milk.” But really it is the pouring that interested Cage the most, the process.

Regularly throughout, Cage tells his listeners where he is structurally in the lecture, which is made up of large and small sections in mathematical proportions. He makes observations about society and music but undercuts himself, repeating, “Slowly, as the talk goes on, we are getting nowhere and that is a pleasure.”

Wilson is the nowhere man. At the point where Cage writes that it is OK to go to sleep if you are sleepy, Wilson got up from his chair and deliberately walked to a bed at the other side of the stage, got under the sheets and closed his eyes. We then heard a recording of Cage reading from the lecture, while, for whatever reason, a photo of the avant-garde Soviet poet and playwright Vladimir Mayakovsky was projected.

Wilson read Cage mostly deadpan, honoring the pauses but giving words his own stresses (partly that seems for theatrical effect and partly simply the result of remnants of his Texas accent). He was more emphatic and less gentle than Cage. But what proved extraordinarily is that, for all his severe posturing, Wilson looked very vulnerable on stage, as if confronting the most essential reason for his theatrical being.

The deep meaning of “Lecture on Nothing” is that by reducing everything to nothing you begin to understand that art is the experience of the moment, that all that matters is now. You can never possess art.

Wilson makes exceptionally beautiful things. His stage props belong in museums. Yet his theater is non-narrative, only understood by experiencing it, living it.

“All I know about method,” Cage writes at the end of “Lecture on Nothing,” is that when I am not working I sometimes think I know something, but when I am working, it is quite clear that I know nothing.” Others might call that enlightenment. Wilson, sublimely, showed why

At that point Wilson lifted his hand for a microsecond and then the stage went black.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.