Review: ‘The Gildless Age’: A different tale of the ‘1 percent’ at the Torrance Art Museum

- Share via

When some of the gilding gets stripped away from our New Gilded Age, defined by the concentration of income and wealth that fueled the incredible rise of the “1 percent,” what is left behind? A new show at the Torrance Art Museum has some thoughts.

For “The Gildless Age,” an apt if rather clumsy title, guest curator Denise Johnson brings together work by a dozen West Coast painters, sculptors and photographers. A bit uneven and ultimately somewhat sparse, the show is nonetheless a welcome attempt to parse deep connections between art and society at large.

Some discoveries are not unexpected.

Rosa Hernandez, the cleaning lady, is artist Claudia Cano’s alter ego, a character who performed at the exhibition’s opening earlier this month. Hernandez, typically invisible as a behind-the-scenes worker who keeps things in order, turns up again in the galleries as an art object: a documentary photograph paired with a sculptural still life composed of a broom and dust pan.

That artistic gesture is slight. But art is always a prime Gilded Age adornment — a generic sign of status and symbol of civilized discernment, even when unwarranted. So Cano/Hernandez is not merely engaged in sweeping the floor; as a work of art, she’s also busy sprucing up rapacious reputations.

A similar motif undergirds a quiet, multi-channel video by the duo Jeff & Gordon (artists Jeff Foye and Gordon Winiemko). Their flat-screen triptych “Temporarily Embarrassed,” made in the grim aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, shows three Inland Empire houses at various price points, each being spruced up for reentry into the real estate market. Two upscale fellows in tennis whites pull weeds and trim a dead lawn, wash a dirty Toyota parked in the driveway and set up a Halloween decoration in the front yard.

Notably, the fright-night embellishment is a giant pumpkin that repeatedly pops its top to release a cheerful ghost trapped inside. Like something from a Charles M. Schulz “Peanuts” comic strip, it’s a playful specter of suburban anxiety.

“There are three things I have learned never to discuss with people,” Schulz’s Linus famously said. “Religion, politics and the Great Pumpkin.”

The videos are structurally odd, which is constructive. The left image appears to be static, like a screen-grab. The others are mostly static, until you look closely.

Water dribbles out of a garden hose and a breeze ruffles leaves in the central car-wash work. Over to the right, that jack-in-a-box ghost keeps reemerging from the big fat pumpkin, as if on a loop.

Forced to look closely and scrutinize the pictures, a viewer begins to wonder who these two men in white are. Helpful brokers? A gay couple gentrifying a ravaged neighborhood? Exploitative real estate investors?

Reading from left to right, the sequence moves from static and stuck to getting back to normal — which is where the great pumpkin lurks. Jeff & Gordon infuse the scenes with a subtle, churning sense of cyclical inevitability and frail response.

There are three things I have learned never to discuss with people: Religion, politics and the Great Pumpkin.

— Linus, from Charles M. Schulz’s "Peanuts"

Two groups of Realist paintings by Marc Trujillo are standouts.

Five small oils on panel, each about 8 inches on a side, frame fast-food workers in visual prisons defined by drive-up windows. The quick but intimate encounter between buyer and seller is frozen in time, but the faces are obscured. The workers are for once subjected to a close scrutiny that the compositions finally thwart.

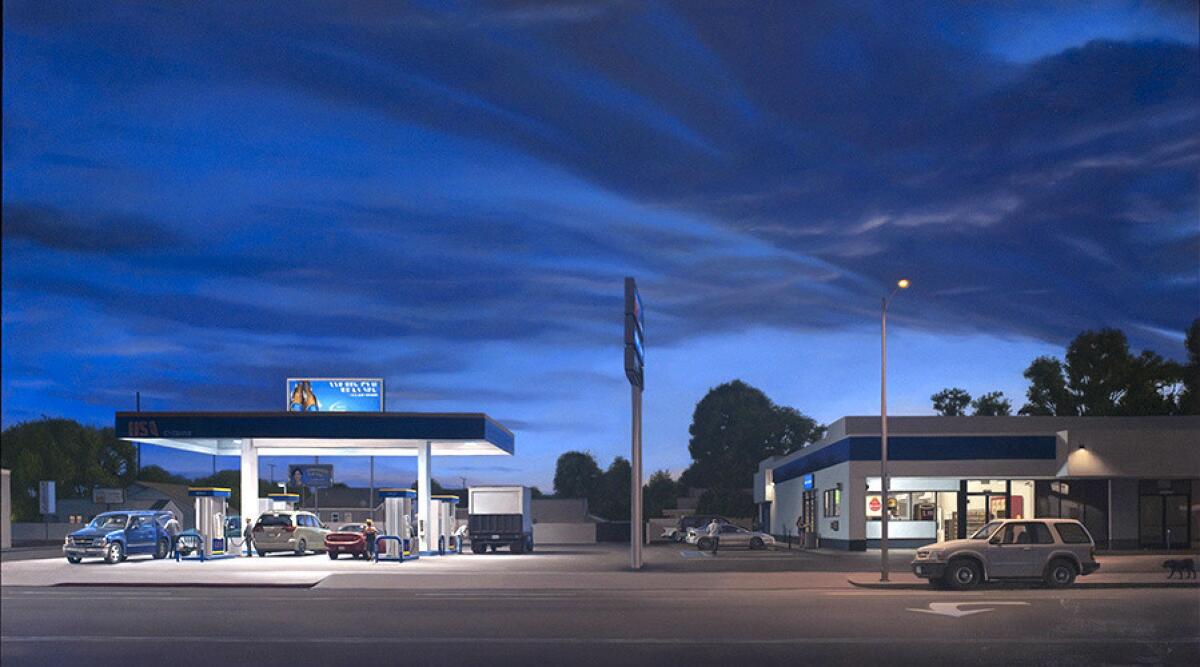

Elsewhere, two large paintings are from Trujillo’s extensive series of suburban landscapes. (The largest is roughly the width of a John Constable “six-footer” extolling the bucolic pleasures of the early 19th-century English countryside.) One shows a gas station infused with the artificial light of fluorescent tubes and signage beneath a dusky sky, the other a car wash featuring an artificial waterfall cascading down a lava-rock wall. Both are viewed frontally from the middle of the street.

Like the fast-food windows, these landscapes are views of ordinary places seen not in passing — which is what they were designed to accommodate — but from a steady vantage one rarely if ever assumes. Try it on Ventura Boulevard or Vanowen Street, and you’d be roadkill.

“14114 Vanowen Blvd.” is painted with slick oils on a polyester scrim stretched taut over an aluminum panel, which results in an almost brushless, visually unnerving surface. The precision technique effectively renders the commonplace alien. Similar subjects have been conventional in American Photorealist paintings since the 1960s, but Trujillo lavishes such extreme care and attention on his epic yet unsightly vistas that they seem somehow excruciating.

Precisely how these affecting paintings elucidate the underpinnings of a specifically Gilded Age theme is unclear. The same goes for Bijan Yashar’s photographs of overhead power lines, which are like sky-drawings that split the aerial image into equal halves; the light-sucking, deathly black-glass casts of tools and obsolete appliances — touch-tone telephone, hand drill, cassette player — by Jane Mulfinger; Colin Chillag’s charmingly cartoonish landscape painting of a desert city built from commercial logos and automobile traffic; Jeff Cain’s alarming video of a children’s science-fair weather balloon that grabs the attention of a private weapons manufacturer’s drones; and others.

Resource usage, the corporate economy and gratuitous commodity consumption are certainly integral to the shape of American social functioning. They have been at least since Mark Twain wrote his satirical novel “The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today” with Charles Dudley Warner in 1873. But that “today” and this today are not the same; the more rigorous the art, the better in elucidating where we are now.

An eclectic range of work by Andrea Bowers, Sean Duffy, Ramiro Gomez, Justin John Greene, Elana Mann, Julie Shafer and Dee Williams completes the show. Of them, the most compelling piece to evoke a distinctly contemporary brand of soulessness is Duffy’s sculpture, “Steelcase.”

A putty-colored pair of back-to-back filing cabinets is cut out in the center to form a square doughnut shape. The exposed interior is composed from continuous redwood slats; their meticulous hand-fabrication would do Donald Judd proud.

Duffy’s fusion of Pop and Minimalism visually squares a circle, an insoluble problem proposed by ancient mathematicians. Its emptiness resonates.

------------

‘The Gildless Age’

Where: Torrance Art Museum, 3320 Civic Center Drive, Torrance

When: Through Oct. 29

Information: (310) 618-6388, www.torranceartmuseum.com

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

'Doug Aitken: Electric Earth': Why MOCA's big new show has too few sparks

11 don't-miss art exhibitions for fall: Quaytman, McLaughlin and a 'Shimmer of Gold'

What this MacArthur winner, an expert in African American art history, plans to do with her grant

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.