Appreciation: Remembering John Mason, the L.A. artist who helped to lead a revolution in clay

- Share via

The first thing I learned about John Mason, who died Sunday at 91, was that he made big things out of clay. Very big things. Rough, abstract sculptures and walls that had to be fired inside a walk-in kiln. Artworks that required the strength of more than one man to move.

That was the basic art-world truth about Mason in the early 1960s, and I got the message long before I met the man. Although I saw his early, breakthrough work, we lived in different parts of the country for about 20 years, including his decade in New York from 1974 to 1984. But my interest in his art never waned, and I eventually made up for lost time conducting interviews, making studio visits, reviewing his exhibitions and writing an essay on him for a book.

For the record:

3:45 p.m. Jan. 23, 2019An earlier version of this article misstated John Mason’s age at the time of his death. He was 91, not 92.

The wait was worth it. This, after all, was the guy who joined forces with Peter Voulkos and other adventurous artists at the Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design) in the mid-1950s and helped to lead a revolution in clay.

Suddenly, it seemed in those days, clay was hot — and cool. No longer restricted to utilitarian objects and fussy decoration, clay could be pushed to its physical and expressive limits. Best of all, it didn’t have to be craft; it could be art. And that made clay irresistible to a variety of artists, most notably men who had resisted craft-rooted media as the stuff of hobbyists but were drawn to the idea of breaking boundaries and ripping up rules.

Mason credited Voulkos, who has a god-like presence in the history of ceramics, and Susan Peterson, who taught ceramics at Chouinard Art Institute, just a few blocks from Otis, with pushing him to make art his own way.

“I had a studio, and I had access to the materials and the equipment,” he told me in a series of interviews at his downtown L.A. studio in 2002. “It was like, here’s the challenge: Mix up a ton of clay and go to work. To make it happen, for me, was to make sculptural pieces and to make big walls. There were no prescriptions for any of this that I knew about. It was, do it and see if it works. And if it doesn’t work, change it and make it work.”

Among the results were walls that stand 7 or 8 feet tall and stretch out 14 or 15 feet. Composed of rugged tiles or overlapping strips of clay, they can feel like stately barriers, masses of natural forms or the imprint of an artist with energy to burn.

Although Voulkos would always be revered as the catalyst of the revolution, Mason became known for transforming clay into expressive art on a grand scale. In Los Angeles, he came into public view in 1966, when his work filled the plaza of the year-old Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Wilshire Boulevard. The critically acclaimed, star attraction was “Red X,” a red-glazed sculpture measuring nearly 5 feet square and 17 inches thick, which landed in the museum’s permanent collection.

A few years later, Mason revealed remarkable versatility by building modular installations of firebrick. “Hudson River Series,” an exhibition of firebrick works individually designed for museums nationwide, introduced him to a broader audience in the 1970s. Then, in the mid-1980s, he returned to clay and developed ideas for hard-edge, twisted forms made of smooth slabs.

The breadth and volume of Mason’s art and the huge industrial space where he worked and lived with his wife, Vernita, and their children, created an image of an independent tough guy, which he was. But as those who knew him well understood, Mason was much more than that.

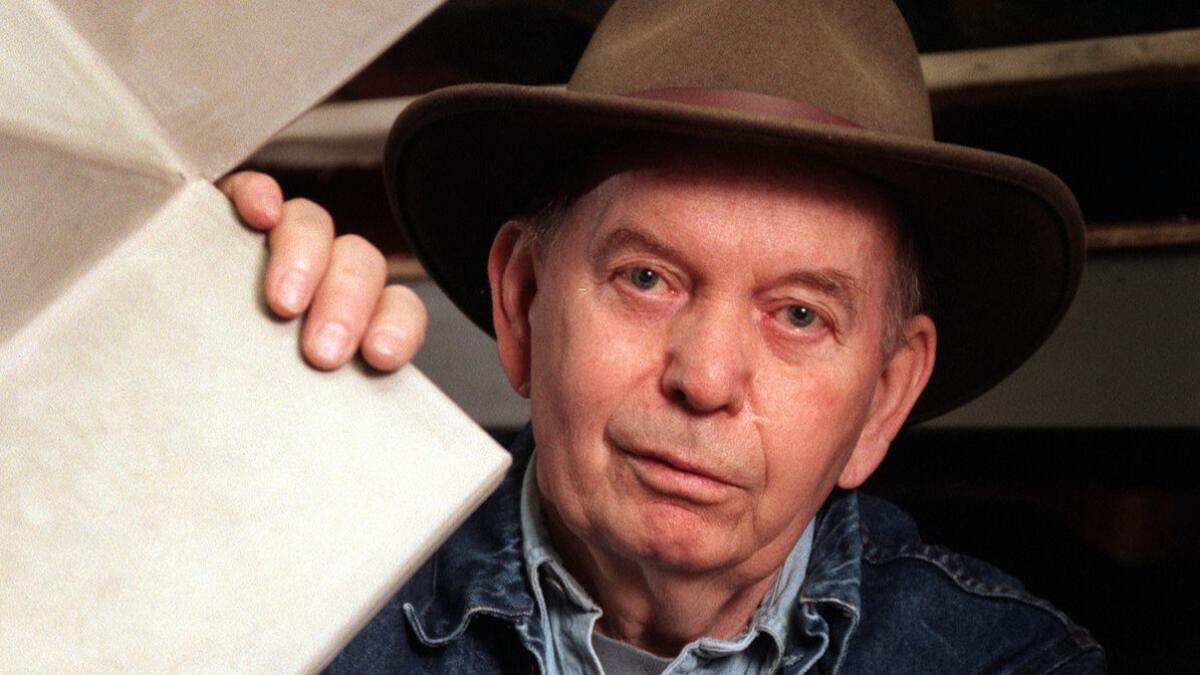

When I met him, I was shocked that he was not a giant hulk of a man. He was compact — just as tall and stocky and muscular as he needed to be. He was also unusually contained, like the chunky cross shapes and “Spears” from the 1960s. Somehow he seemed to embody the quiet, purely natural force that resonates from his work.

If it doesn’t work, change it and make it work.

— Artist John Mason

His interior being was far more complex. Soft-spoken, thoughtful and well-read, he could seem incomprehensibly taciturn to his students at Pomona College in Claremont, at UC Irvine and at Hunter College in New York.

“Often language gets in the way of understanding form and space or pattern, but the challenge for me as a teacher was to use both,” he told me. “I always liked teaching, just for that simple reason.”

Stories about Mason’s long pauses, followed by thought-provoking remarks, abound among his former students. But many — including James Turrell and the late Chris Burden, internationally renowned artists who studied with Mason at Pomona — admired him as a man of few words who taught by simply being “a real artist” and letting them learn from their own mistakes.

As I plied Mason with questions over the years, I got to know a man who was born in Madrid, Neb., spent his late childhood and teenage years on a farm in western Nevada and headed for Los Angeles in 1949. “I had a great desire to learn about art but not much opportunity to discover or explore,” he said. “There were no artists or galleries or art museums. Still, I had great curiosity about what potential that field might have for me. I knew there was another world out there.”

The last time I saw him, on Sept. 15, 2018, he was in his element, seated in a wheelchair at the opening of “Meditation on Material: John Mason’s Firebrick Installations,” his final exhibition, at Scripps College in Claremont. His assessment: “It’s good.”

Support our coverage of local artists and the local arts scene by becoming a digital subscriber.

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.