Review: It takes a striptease to enliven ‘Stories of Almost Everyone’ at the Hammer Museum

- Share via

Wall labels, catalog essays, audio guides, critical reviews, gallery docents, press releases — the interpretive apparatus that grows up around Conceptually-based art in museums can be a dreadful subject for an exhibition. Organized navel gazing is usually an unattractive sight.

And so it turns out to be in “Stories of Almost Everyone,” an extravaganza of excessive self-contemplation newly opened at the UCLA Hammer Museum. The show assembles art objects that reside within a context of heavy institutional mediation, given the nature of the work.

A ring whose stone is said to be made from the compressed ashes of a deceased architect of international stature; a tall, canary-yellow plank leaning against the wall and virtually reproducing sculpture by a famous (also deceased) artist; an ordinary 12-tier postcard holder, the same kind you’d find in a tourist shop, here empty of cards — these are among the objects scattered like so many tumbleweeds throughout the Hammer’s wide-open rooms.

With the visually dull little ring, you wouldn’t know about artist Jill Magid’s otherwise fascinating obsession with the architect (Luis Barragán) just by looking at it. Some text is necessary to reveal to an unwitting viewer the morbid material claimed to be embedded in the jewelry’s dark blue-gray stone.

Unless you are knowledgeable about 20th century art, you may not identify the celebrated sculpture of John McCracken as source material for Darren Bader’s bright yellow plank. (Undated, it approximates a 1980 McCracken in the Baltimore Museum of Art.) Nor would you catch the historical reference to the skeletal shape of Marcel Duchamp’s 1914 readymade sculpture, “Bottle Rack,” in Ceal Floyer’s readymade postcard rack, “Wish You Were Here.”

But help — of a sort — is on the way.

Each of 62 objects by 40 international artists (plus one other that is a performance, not an object) is accompanied by a prominent wall text, either flatly explanatory or interpretive. All of the texts are reprinted in the handbook-sized catalog.

Meanwhile, audio guides and headphones are available to take with you while perusing the art. They are accompanied by a printed transcript for those who prefer to read rather than listen, or to read along with while the institutional voice whispers into your ear.

According to Hammer curators Aram Moshayedi and Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, the premise of “Stories of Almost Everyone” is that we have a “tendency to project stories onto inanimate objects, including works of contemporary art we encounter in museums.” These objects demand a suspension of disbelief.

An introductory wall text explains, “Contemporary art museums are tasked with facilitating access to the hidden truths embedded within works of art.” The show means to tease out the way those stories emerge in an institutional setting.

It is focused on art of a particular kind. All but four of the artists are under 50, which means they (like the curators) were born into a world where Conceptual art was already on its way to becoming the widespread cultural reference point that it is today. Once radical, it’s now establishment.

Two types of Conceptually based works are featured.

One is found objects placed into a new context — such as Floyer’s ordinary postcard rack, a structure recalling the genre’s original souvenir in Duchamp’s bottle rack. Others include Michael Queenland’s broom, standing upright as a monolith to some unseen sorcerer’s apprentice; the big library globe once owned by Robert McNamara, the Vietnam War-era secretary of Defense, repurposed as an ironic, socio-cultural collectible by Vietnamese artist Danh Vo; and, yesterday’s newspaper, which is refreshed daily on a low, doormat-like pedestal by Dave McKenzie, ostensibly to offer insight into sluggish analog communication in a lightning-fast digital era.

The other Conceptual trope consists of found objects slightly altered. Fayçal Baghriche apparently tinkered with a vintage mantle clock to speed it up, warping time. Cian Dayrit merged an upholstered prayer bench with a decorative boudoir vanity, topped by a carved imperial eagle.

In the most dramatic example, the mechanized lid of a white baby-grand piano periodically lifts and then crashes down with a thundering bang! chased by the clatter of shaken and vibrating strings. Martin Creed reimagines a player piano as a disruptive rather than soothing noise machine.

Few of these works really require the explanatory textual interventions that the curators assume they do. However, with viewers feeling obliged by the show’s premise to read the labels and peruse the audio guide, an unhappily coercive element creeps into to their undertaking. Perhaps because the Hammer is a university museum, therefore heightening the pedagogical concerns of its exhibitions, specific institutional imperatives are made to be of outsized interest.

Here, the museum and its issues get in the way of art’s encounter with an audience.

“Now more than ever,” the catalog imprudently instructs, “it is clear that embedded within the desire for meaning in art is a latent desire for narrative, for some semblance of stories to give shape to an otherwise indeterminate experience.”

Note the unfounded assumption: Whose “desire for meaning”? The desire of the audience? The artists? The museum?

This anxiety-laden emphasis on the supposed necessity of interpretive explanation — of storytelling — is what Susan Sontag once called “a subtle or not so subtle form of philistinism.” Art is being required to justify its existence with “meaning.” It’s legitimacy will apparently be assessed by the seriousness and significance of the story line.

“Stories of Almost Everyone” is a tale of institutional anxiety. The condition surfaces most clearly in the 63rd work in the show, choreographed by the 41st artist. It is not an object. Instead, it’s a situational action.

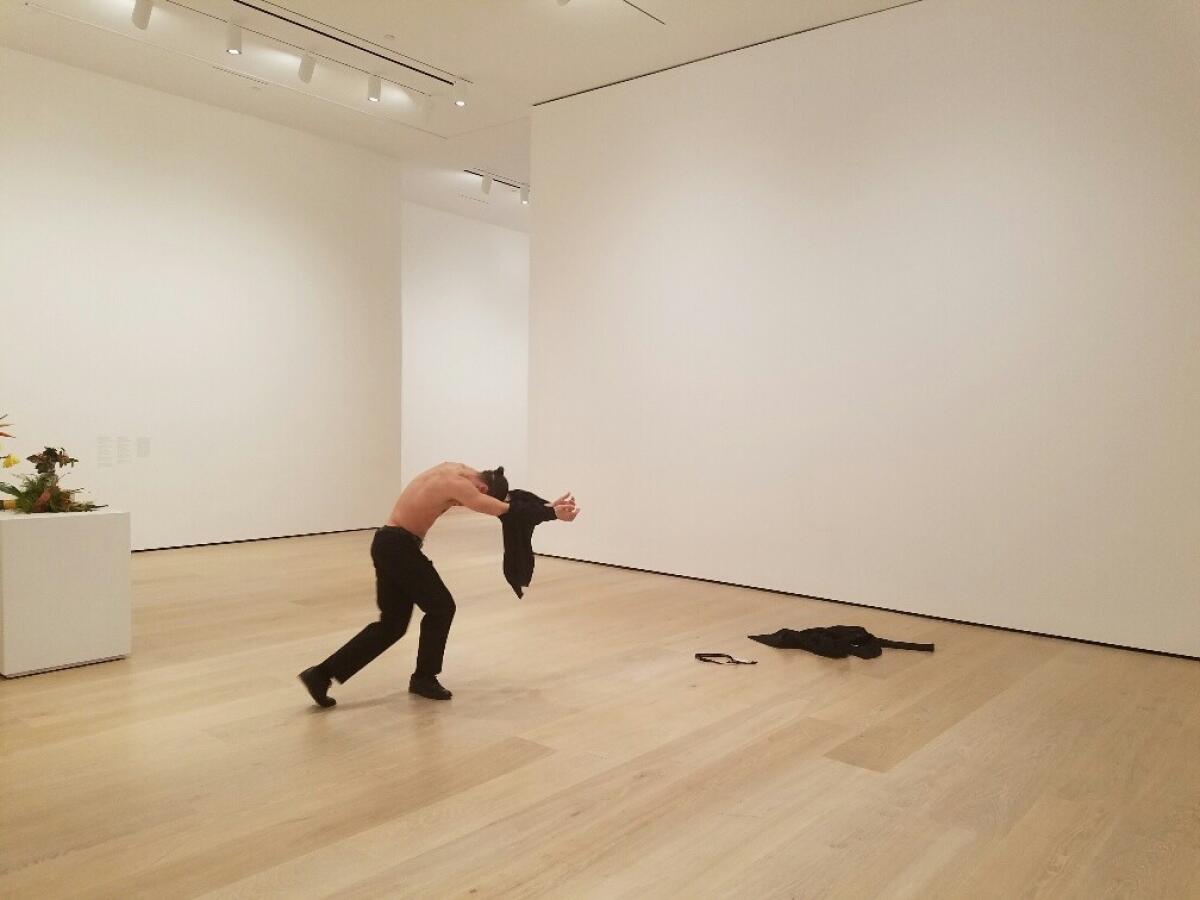

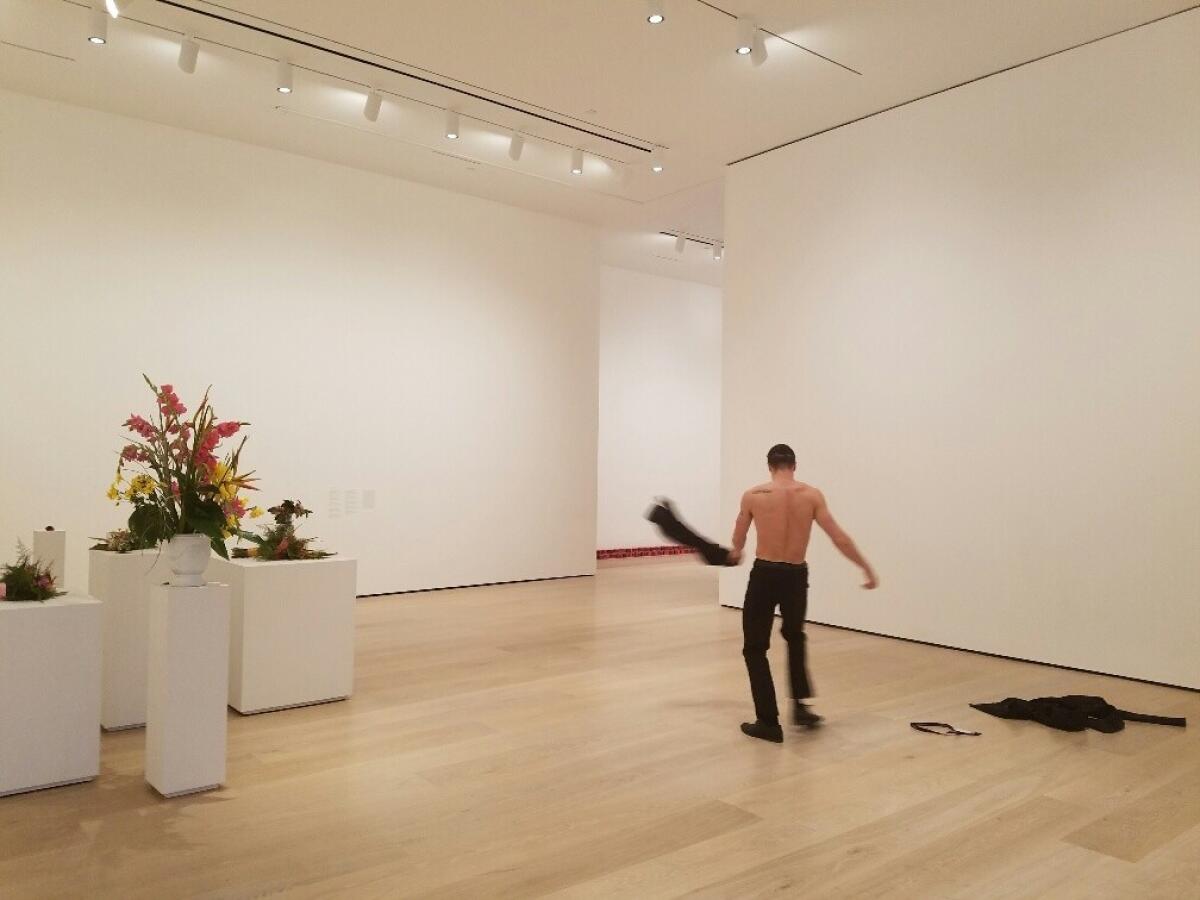

The brief performance is also the one real bright spot in the exhibition. Enter the show’s final gallery and, suddenly, a uniformed guard standing nearby begins to writhe, twirl and dance.

Soon the clothing begins to come off. The dance becomes a silent, wholly unexpected strip-tease.

The ecdysiast’s disrobing ends just before the underpants — given a couple of teasing tugs as the stripper looks you squarely in the eye — would typically get discarded in the climatic moments of a commercial bump and grind.

Like the cliché cop who in fact is a secretly hired stripper arriving at a noisy bachelorette party, the museum guard is a figure of institutional authority who’s not what he appears to be. In artist Tino Sehgal’s wryly seductive work, coyly titled “selling out,” surface layers get peeled back from this institutionalized work of art to reveal what lies beneath — in this case supple skin.

Yet the process stops just short of exposing the ultimate creative apparatus. That part is private.

On the day I saw the show, a funny moment came when I realized that, as the stripper enticingly unfurled a Scheherazade story on one side of a gallery wall, on the other side a docent was droning on about one of the mute sculptural objects. The docent spoke to a crowd of a couple dozen visitors who had gathered on neatly arranged folding stools to hear the dutiful explanations. The stripper played to virtually no one in a mostly empty room.

You certainly feel uneasy in a gallery encounter with a guard getting naked. That’s salutary. The mediation of gallery docents, wall labels, audio guides and the rest mostly exists to lessen the anxiety that an audience naturally feels — and frankly ought to feel — when faced with a powerful work of art.

I couldn’t help but wonder what it would be like to come across Sehgal’s action not in this pedantic show but over in the Hammer’s ordinary permanent collection galleries. Imagine if an attractive guard suddenly began undressing in the vicinity of Gustave Moreau’s 1876 masterpiece of erotic sensory experience, “Salomé Dancing before Herod.”

Now that would really be something — no label needed.

Twitter: @KnightLAT

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Stories of Almost Everyone’

Where: Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., L.A.

When: Through May 6; closed Mondays

Admission: Free

Infomation: (310) 443-7000, hammer.ucla.edu

MORE ART:

What's next for Pacific Standard Time? Here’s one idea

MOCA’s gala and questions of a straight-white-man problem

The late Dora De Larios melded Mexican, Japanese and Modern

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.