Frank Gehry and others imagine a Grand Avenue that is a destination for everyone

- Share via

Frank Gehry

Frank Gehry is the architect of the Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Grand, a mixed-use development — with a hotel, residences and shops — scheduled to open across the street from the hall in 2021.

Can you talk about the significance of Grand Avenue?

I think that what has been missing on Grand Avenue is nightlife. When many people drive halfway across the city to get to a concert or museum, they would like to maybe have dinner or stay late.

The hope for the Grand is that it will be kind of the grease on the wheels of culture, that it will bring about all that activity. It may also provide the possibility of projecting concerts on Disney Hall [which was part of the original plans for the building], since that could be a major attraction for the new restaurants, where people could watch. I think that will happen.

What about the future?

What’s interesting is that the new halls [Gehry is designing] for the Colburn [School] are going to be down the hill on 2nd Street. The connections now are going east rather than south, and that makes more sense to me. If you look at what’s available east, you’ve got Chinatown, Little Tokyo, Olvera Street. And with this, you’ve got the beginnings of a population that we all hope we can connect to.

FULL COVERAGE: Grand Avenue project »

[Going east] leads you right to the Geffen Contemporary, which is about to have a renaissance, and then to the Los Angeles River [the full length of which is Gehry’s major urban renewal project], where we’re proposing a big water park. It would be like an Indian step well in reverse, a place to store water — one month wet, 11 months dry. Man, if we can pull that off, it would change the whole city.

— Mark Swed

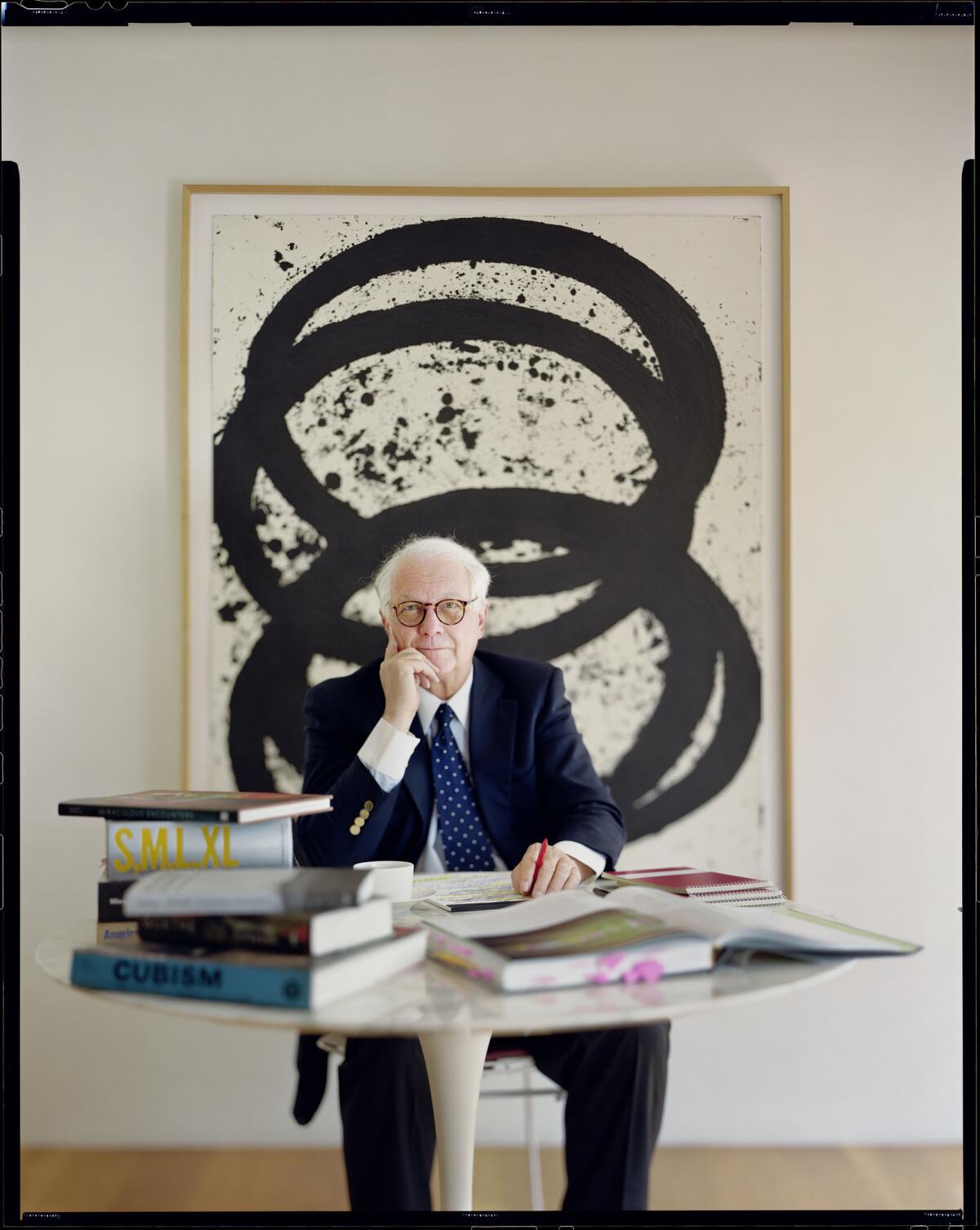

Richard Koshalek

Richard Koshalek was chief curator and deputy director of MOCA from 1980-82 and museum director from 1982-99.

Can you talk about the significance of Grand Avenue?

When we built MOCA, there was nothing around it. And since there was commitment for some kind of art function to California Plaza, we first started a “guerrilla” museum, with the idea of art as guerrilla warfare. We closed Grand Avenue for [L.A. choreographer] Rudy Perez, invited [L.A. performance artist] Rachel Rosenthal to create a work on the parking lot of the Water and Power building and had performances on the loading dock of the Mark Taper Forum. The idea was to bring a certain kind of creative energy to Grand Avenue even before the museum was built.

What about the future?

When I chaired the competition for an architect for Walt Disney Concert Hall, initially we wanted to remake all of Grand [Avenue], and Frank Gehry’s hall and his designs for the Grand across the street — which were always to be part of the project — have helped do that for sure. But nobody has thought seriously about what Grand Avenue should be as a major public space. We use the wrong examples when we look to European models. Los Angeles is not Paris. We need to come up with our own ideas, be aspirational.

The reason Gehry won the Disney Hall competition is because he understood both L.A. the city and the L.A. Phil. Now we need to do the same for the street, which we’ve forgotten. What if [L.A. Mayor] Eric Garcetti became our Napoleon III and sponsored a competition to find the brightest minds who could design a public space appropriate to our climate, transportation needs and culture? We could commission landscape artists and use “lower Grand” for new kinds of art installations. In thinking about the future L.A., has to have a continuous confidence to come up with designs not modeled on any other city, and then build them.

— Mark Swed

Catherine Opie

Fine-art photographer Catherine Opie is a member of the board of the Museum of Contemporary Art.

What role does Grand Avenue play in the cultural landscape of Los Angeles?

I’ve been living in L.A. since ’85, and I’ve watched downtown go through moments of: “Yes!” And then, “Crash.” But I think that the most interesting thing, in terms of the cultural corridor now, is they actually have a population to support the arts, which is very different than how [it was].

With L.A. [so spread out], there was always the question of: “How do you get the Westside downtown?” And now, it comes downtown because of everything that has been built in relationship to the cultural corridor. And that even includes Staples Center in my mind. That allows another demographic to come downtown where they go, “Oh, I wanna be down here.”

What could, or should, the Grand Avenue culture corridor be going forward?

I would like to see it grow in relationship to affordability, to a certain extent. My biggest concern about allowing a city to truly grow is that it can’t only grow for a certain economic [demographic] in relationship to art and culture. We have to allow for [the development of] more affordable housing.

I think it would be interesting, as art institutions build these fantastic buildings, that there somehow be a component of it that [involves] affordable housing, [to allow for] 20% of a building to be occupied by low-income renters or even purchasers. I was an artist who moved to L.A. because it was more affordable than San Francisco or New York, [but] we are now losing a younger group of artists. Can the corridor and the arts initiative also support the artists who want to live here within this community? I’m talking about housing. It’s a real problem within our city.

— Deborah Vankin

Christopher Hawthorne

Christopher Hawthorne, chief design officer for the city of Los Angeles, was the architecture critic at the Los Angeles Times from 2004-18.

What role does Grand Avenue play in the cultural landscape of Los Angeles?

For a long time I’ve been of two minds about the larger cultural significance of Grand Avenue. Seen from a certain angle it would be almost impossible to overstate its importance for American architecture and urbanism. It's not just that there are prominent buildings by Arata Isozaki, Elizabeth Diller, Frank Gehry, Welton Becket, Wolf Prix and Rafael Moneo lined up in a tidy row.

In a broader sense, Bunker Hill has been a petri dish for urban-planning theory for more than a century, a place where early suburbanization gave way to an aggressive urban-renewal campaign and more recently to investments in transit, green space and infill development, and a big bet on the power of celebrity architecture. That complicated history, though, has made Grand Avenue something of a sinkhole for the attention of city officials, arts patrons and newspaper editors. Relative to other parts of the city, we’ve given it more public subsidy and private largess than seems equitable. We’ve also written and argued about it endlessly, thanks in part to close connections between Times leadership and Bunker Hill that go back to the days of “Buff” Chandler and the birth of the Music Center.

What role can it play ... what role should it play ... in the future?

The experiments in urban planning and evolving models of patronage that have shaped Grand Avenue street have left us with a peculiar artifact with plenty of 21st-century potential. Precisely because it is more Frankenstein's monster than traditional neighborhood, Grand Avenue is a place where forward-looking architecture and urban design might continue to take root. And so even as we try to steer clear of the hubris that marked the city planning theories of the postwar decades, it would be a mistake to seal Grand Avenue as it exists now in amber in the name of penance or newfound caution. That would have the effect of enshrining the very mistakes — top-down, car-oriented planning and the displacement of residents, to name the biggest — that urban renewal wrought.

A new tower planned at the base of the Angels Flight funicular, Frank Gehry's expansion of the Colburn School and the redesign of the Music Center plaza by Rios Clementi Hale Studios will continue the long process of filling in and activating the giant gaps opened by those 1950s planning decisions.

Looking ahead, our focus should be twofold: finding sites on Bunker Hill for a significant new supply of affordable housing (near or above the forthcoming Metro Regional Connector station on Hope Street would be one place to consider) and rethinking the pedestrian and mobility experience from the sidewalk up, so that the space between the famous buildings becomes as compelling as the buildings themselves.

— Alice Short

Paul Schimmel

Paul Schimmel was chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art from 1990-2012.

What's the cultural significance of the Grand Avenue corridor? What does it add to the city?

The Grand Avenue corridor, like the Wilshire corridor, began with really large institutional anchors: LACMA [on Wilshire] and the Music Center [downtown]. They represented a kind of ’60s vision of an area.

It’s now a destination, both for the community and it’s a destination for tourism. And the more elements that are there, the greater the critical mass is. Big, institutional, not-for-profits — libraries, music halls, museums on an institutional scale — this is what they’ve done very well. But it’s in some ways the random things that you don’t plan for that make the whole community of Grand Avenue come to life. I think what has happened in the gallery world over in Chinatown, and downtown, and now the Arts District, all of the smaller and medium-sized not-for-profits and commercial ventures, have brought a far richer, far more diverse program [to the area].

How could the Grand Avenue area be more fully realized?

I think MOCA has tried over the years, and I know the city has talked about over the years, different ways of trying to connect Grand Avenue, which still feels in some ways corporate, a little isolated on top of the hill, a little hard to get to. It doesn’t have the kind of walking community the Arts District has. And thinking about trying to connect these two very different-in-feeling but geographically-so-close communities would be something that would be a good mix. I think public transportation. I think parking, I think shuttle buses, and I think art that literally connects those two communities — we need far more public art. Compared to so many other cities, Los Angeles doesn’t connect the dots and art in the best way.

So what might that look like on Grand Avenue in the future?

I’d like to see smaller and medium-sized places up on the hill – galleries, not-for-profits, cultural institutions, music. I think trying to connect the arts district from 7th all the way over to Little Tokyo, up through Grand Park and up to Grand Avenue, this would be a great accomplishment.

— Deborah Vankin

Klaus Biesenbach

Klaus Biesenbach is the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art.

What role does Grand Avenue play in the cultural landscape of Los Angeles?

I think, in a beautiful way, it embodies and materializes the center of a very huge urban environment. There’s this incredible density with all these institutions — you have Disney Hall, the Music Center, the Broad, MOCA, the cathedral, the soon-to-be new Grand. It’s a beacon of culture. And you can see the density — this is the unique opportunity Grand Avenue has.

What does it mean for MOCA to be on Grand Avenue, as opposed to elsewhere in the city?

I’d turn the sentence around: “What does it mean for Grand Avenue that MOCA is here?” … it’s very important that MOCA is one of the points of origin on the cultural corridor. It’s meant a lot for Grand Avenue that MOCA is here — as an idea and as a building. And we’re [relighting the MOCA building’s] pyramids, and the whole building will become more and more visible in its role as one of the points of origin of this cultural corridor.

What role should Grand Avenue play in L.A. in the future?

I would say it should be collaborative, because the synergies that could be between all of these cultural institutions is immense. The tide is raising all ships. And I think a concerted effort with all the Grand Avenue institutions really working together is extraordinary and is internationally attractive. It’s just unique.

— Deborah Vankin

Hernan Diaz Alonso

Hernan Diaz Alonso is director and chief executive of the Southern California Institute of Architecture.

What role do you see Grand Avenue playing in the cultural landscape of Los Angeles?

It has been an evolution. I moved here in 2001. Disney Hall was still under construction; the cathedral was still under construction. Today, you have almost all aspects of the city here, from religion to education to leisure to art. It has become a hub of culture, and you have it all compressed into three or four blocks, all world-class institutions, with programming that is very open-minded and progressive.

Design-wise, what has been key to having this area play a more significant role in the city’s life?

All of these institutions, they’ve all done a good job of making many things available to the public — the Broad with the garden outside, and MOCA with the plaza. But I consider Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall a masterpiece — and not just because of the design, but the attitude. As a building, Disney said, “We need to engage the city. We need to engage people. We don’t need fortresses anymore.” Gehry prioritized the pedestrian in an era in which the typical L.A. building still privileged the car.

How would you like to see Grand Avenue evolve in the future?

Grand Avenue is a dream of Modernism. It is elevated, it is still car-centric. L.A. needs more density, and the area needs a little more messiness, more hybrids, more life. It will need to mutate and evolve. So, hopefully, the Grand Avenue project they are doing in front of Disney Hall is the first step. My aspiration is that these institutions become a part of everyday life. But in order to do that, the city needs to grow up around it.

— Carolina A. Miranda

Chad Smith

Chad Smith is chief operating officer of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Can you talk about Grand Avenue in the present?

With all the new venues along Grand Avenue, from the performing arts high school to the Broad and the Colburn School additions and rethinking Grand Park, the number of performance-seat nights is set to almost double from what it was just a few years ago. In addition, we’ll see what happens when the Grand opens. This aggregation of resources has gotten us to think more about programming for new spaces apart from our venues, to ask what is the best space in which to hear these works or this piece. This can be seen in the way that the L.A. Phil has begun doing things on the outside of and around Walt Disney Concert Hall. It also suggests that Grand Avenue is finally starting to have cultural weight the people who built the Music Center always hoped for.

What about the future?

Now the big question is: What does it mean? Is it just that we have a collection of companies and institutions along this boulevard that are producing work for our audiences, or is there something bigger? Is there a reason that we’re beside each other? What does proximity matter beyond ease of access and related activities?

The example that I use is whether we could at last produce Robert Wilson’s “the CIVIL warS” [the daylong opera/theater/visual-art extravaganza commissioned for the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984, created with partners around the world but ultimately abandoned for lack of resources]. That’s the kind of thing that could only happen if all the arts institutions along Grand Avenue work together. And we’re all beginning to test out new collaborations.

— Mark Swed

Helen Leung

Helen Leung is co-executive director of LA-Más, a nonprofit urban design organization that focuses on lower-income and underserved communities.

What role does Grand Avenue play in the cultural landscape of Los Angeles?

Grand Avenue has this amazing role to play in terms of serving as a civic spine to downtown Los Angeles. What I appreciate most about Grand Avenue and its civic institutions is its diversity in programming, especially its level of inclusivity and price points.

What role should Grand Avenue play in the future?

It would be wonderful to have a first-class civic street that is, in its broadest sense, inclusive. That is the issue for Los Angeles: How can you channel these projects and institutions into a space where everyone feels welcome, so everyone feels art and culture is something for them and not just for someone who has money?

California recently decriminalized street vending. Los Angeles is still working on a system for street vendors. Will Grand Avenue welcome street vendors in the future? And what about affordable housing? As someone who is a child of working-class immigrants and co-runs an organization that is trying to explore affordable housing, [it] should definitely be included on Grand, especially when there is public money or public land is involved.

— Alice Short

Kiki Ramos Gindler

Kiki Ramos Gindler is president of the board of directors of the Center Theatre Group.

What role does Grand Avenue play in the cultural landscape of Los Angeles?

With the explosive development and growth of businesses and residences in the downtown area, the organizations along Grand Avenue are being activated to reflect the diversity of our communities. Grand Avenue is becoming informed by the various cultures and arts practices throughout our community. It is becoming a focal point for everyone. There’s an inter-connectivity and dialogue among the arts organizations on Grand Avenue that is unparalleled elsewhere in the country.

What role should Grand Avenue play in L.A. in the future?

I would like to see it become more of a destination. If you live in L.A., it should be at the front of your mind to go there because you don’t know what exciting things are happening, but you know that something exciting will be there. I think the organizations need to think more about an open-door policy and how we can better communicate that we’re open to everyone and not just to be enjoyed by a segment of the population.

— Jessica Gelt

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.