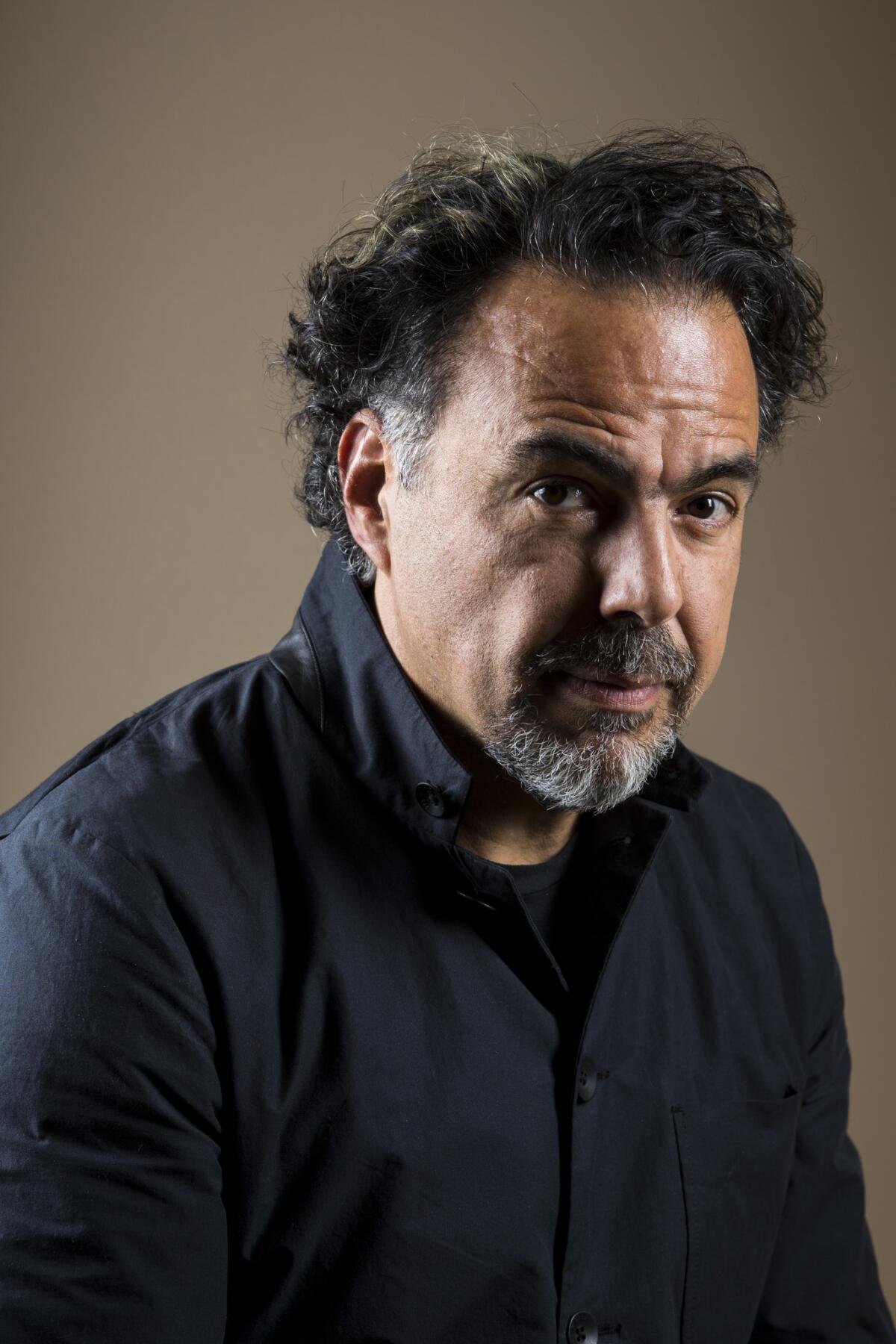

Q&A: How a migrant woman’s death influenced Alejandro Iñárritu’s Oscar-winning VR project ‘Carne y Arena’

- Share via

Six months after giving birth to an unusual project — the virtual reality exhibition “Carne y Arena (Virtually Present, Physically Invisible),” which won a special Oscar on Nov. 11 at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Governors Awards — director Alejandro G. Iñárritu remains impassioned by the artistic and social issues it raises.

The piece is part three-dimensional art installation (occupying three different room-sized environments) and part 360-degree virtual reality film. It takes as its story the perilous desert crossing regularly made by Latin American migrants from Mexico into the U.S. — harrowing journeys that can end in death or in a Border Patrol detention cell.

The VR film’s narrative involving a surreal confrontation with Border Patrol agents was inspired by the experiences of actual immigrants the filmmaker located through Casa Libre, a not-for-profit shelter in downtown Los Angeles. “Carne y Arena” includes filmed portraits of each migrant (and one Border Patrol agent) at the end of the installation, all rendered by Oscar-winning cinematographer and frequent Iñárritu collaborator Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki.

It was to these immigrants — and those from "all corners of the world" — that Iñárritu dedicated the new statuette in his acceptance at the Governors Awards gala.

Sitting over coffee in a sunny meeting room at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where “Carne y Arena” has been on view since July, Iñárritu said winning the special Oscar was in some ways more meaningful than his previous four wins for “Birdman” and “The Revenant.”

In part, that’s because the special Oscar isn’t a competitive category. It’s a discretionary award given by the academy’s Board of Governors only when there is a “deserving recipient.” The last time one of these awards was issued was more than two decades ago, in 1995, when Pixar’s “Toy Story,” the first feature-length computer-animated film, was presented with an award for special achievement.

“It was an acknowledgment more than an award,” Iñárritu said. “And it was an acknowledgment that was not about me. It was something bigger than any of us — and that was the most beautiful feeling.”

“Carne y Arena,” which debuted at Cannes in May and is also currently on view in Milan and Mexico City, has pushed the boundaries of technology and form, bringing together new and old art forms. As academy President John Bailey put it, the VR installation opened “new doors of cinematic perception” and viscerally connected viewers to the “hot-button political and social realities of the U.S.-Mexico border.”

On Thursday, Iñárritu will join LACMA director Michael Govan for a public discussion about the project at the museum. Ahead of the talk, Iñárritu — whose deep, accented English would make him a great voice-over artist if he weren’t so busy directing films — took time to discuss why “Carne y Arena” has been so important to him.

“There is so much blah, blah, blah and so much tweets and nobody is interested in going to the root of why these people are leaving their homelands, their families, their culture — putting themselves at risk, putting their lives at risk, their kids’ lives at risk,” he said.

In this lightly edited conversation, Iñárritu discusses how “Carne y Arena” might get members of the public to consider complex issues in ways that are more profound and more personal.

What inspired you to make “Carne y Arena”?

When I did “Babel,” there was one thing that was happening on the radio at that time in Tijuana, where they were relaying the story of some immigrants. I could never forget that story.

There were like 20 immigrants; they were crossing. A woman broke her ankle and she was with her son of 11 years. [The group] had to abandon her. She stayed behind, under a mesquite with the son. She was very worried about the son. She said, “You have to run.” The kid leaves half a bottle of water with his mother. And I always remember this: He left a little towel with yellow squares on the face of the mother. And she had these white shoes. These people are so unprepared, that they are crossing with wedding shoes.

Anyway, the boy went to find help and he was captured by policemen. He said, “My mom is there!” And they said, “Where?” “She is under a mesquite.” They laughed at him and they sent him back to Oaxaca.

His grandfather — the father of the mother — was working in the United States. He had a visa. The father came down. Nobody listened to him. Three days later, a radio station has mercy on him and they tell his story. The authorities began to move. And they found the woman — they found the bones of the woman. And they bring the bones, the towel and the shoes and that’s how they recognize her.

I heard the story on the radio and the father is saying, “I’m thankful that I could at least bring back my daughter to have a burial with her.” The guy was still thankful about it. It just broke my heart.

That story really stuck with me. At the end of “Carne y Arena,” when the police point at you and everything goes down, you see a yellow towel with squares hanging in the mesquite and there’s some white shoes. That’s my little homage to that woman.

A lot of the coverage of “Carne y Arena” has focused on the seven minutes of virtual reality. But the film occupies a series of environments — including one that evokes the chilly short-term holding cells employed by the Border Patrol, and another that looks like the desert border. Why was creating that setting important to you?

I discovered that VR, even at this level, it was not enough. Knowledge can be an obstacle for wisdom. The way we know things is an intellectual process. But I found that the sensorial part of the piece was essential in giving people an understanding. The breeze and the sand in your feet. Your body doesn’t lie. There is no process. It’s an immediate sensation.

When you feel the cold in the first room, when you see the actual shoes of these [immigrants], you are touching reality. You are touching the life of a person through an object, not through an idea. And I think that is a crucial thing. Then I take you into the virtual reality. But, still, I’m touching you with things: with the sand, with the air.

Then at the end, there is the more status quo piece, [the testimonials], and that is where you go into the intellectual process.

And by that, you mean the immigrant testimonials that are featured in the final room of the installation.

That was so difficult. We shot that the day after Trump won. I said to them, “Don’t tell me with words, but tell me with your eyes what you are feeling.” There are so many things going on inside of it. Then I said, “Now tell me with words.” None of them insulted the president. They are just saying things like, “We are very sorry that they think we are bad people.” They said, “We hope God will change the heart of this man.” They were very noble.

You told Vanity Fair that working in VR was like working in a “completely new grammatical language.” How so?

It doesn’t belong actually to any of the conventional mediums. It has a little bit of theater. It has a little bit of physical installation. It has a documentary element. It has an animation element. It has a film element. It has a pictorial element. It is fed by many media or expressions but it doesn’t belong to any of those.

The language of film gives you a partial reality, a fragmented reality and you have to interpret it. If I shoot two guys in a restaurant talking, you have to imagine the other 360 degrees. I put in audio of people eating and you can feel the room, even if it’s just two people on a set. Your brain fills in the rest.

In virtual reality, I have to give you a multidimensional thing. I have to build the whole thing. It ends the dictatorship of the frame. And [the viewer] is not passive. You are absolutely actively deciding where to go. I can try to manipulate you, but I will have no control. In cinema, I have the control.

Doing virtual reality for me was a big question philosophically. How many great journalists and documentaries have been talking about this problem? But if I would have done a small documentary, nobody would have cared. We are insensitive to reality. Sometimes we have to create a virtual reality to talk about reality.

What are some of the ways in which you have seen people engage with the piece?

It’s incredible. We have everything from people trying to hide behind a bush to people, when the helicopter comes, they start running. There are people who dive into the sand and start yelling, people who start trying to protect the kid. Most people go on their knees when the police point at them. There are people who stay behind the policemen. There are other people who try to help the people. The piece says a lot about who you are.

You’ve written op-eds critical of Mexican President Ernesto Peña Nieto and you’ve made statements in support of the 43 missing Ayotzinapa students. Why is it important to you not to shy away from politics?

One of the things that I didn’t want for this piece is to become political. Politics and politicians have kidnapped our reality. They have degraded our reality. Everything is black or white. This is about talking about humanism. I’m trying to say, “This is not about right or left. It’s more complex.”

People have ideologies and ideas. Their reality is narrow. It becomes very dead. It becomes a box. So I want people to see, to feel with their skin, to walk a mile in somebody’s shoes.

The Director’s Series: Michael Govan and Alejandro G. Iñárritu

Where: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Bing Theater, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles

When: 7:30 p.m. Thursday

Admission: Free; tickets required

Info: lacma.org

‘Carne y Arena’

Where: Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM) at LACMA, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles

When: ongoing

Admission: $30 ($25 for LACMA members) plus $15 general admission. Tickets sold out through Feb. 11

Info: lacma.org

ALSO

Alejandro Iñárritu's virtual reality installation, 'Carne y Arena,' wins a special Oscar

Inside Alejandro Iñárritu's VR border drama at LACMA: What you will see and why you might cry

Cannes 2017: Alejandro Iñárritu's virtual reality project takes film to new frontiers—and questions

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.