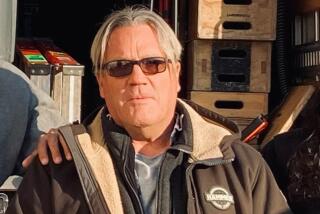

‘Midnight Rider’ director Randall Miller pleads guilty in train death

- Share via

Reporting from Jesup, Ga. — In a case that has become a rallying cry for movie set workers demanding safer conditions, Hollywood director Randall Miller pleaded guilty Monday to involuntary manslaughter in the film-set death last year of an assistant camera operator killed in a train accident.

The plea marked a seminal moment in Hollywood film history. Entertainment industry attorneys said they could not recall another case in which a filmmaker had pleaded guilty to criminal charges over an accident on set.

Assistant camera operator Sarah Jones, 27, was killed Feb. 20, 2014, when a train crashed into a set on a trestle during the first day of filming of “Midnight Rider,” a biopic about Southern rocker Gregg Allman. At least six other crew members were injured.

“It sends a message, frankly, that if you do not respect those that you’re in charge of, you may end up behind bars,” said Richard Jones, Sarah Jones’ father, as he stood outside the courthouse. “I think that will get attention.”

Miller’s lawyer said the director’s plea was intended to spare Miller’s wife and business partner, Jody Savin, from prosecution. Involuntary manslaughter and criminal trespass charges against Savin were dropped.

Miller, who also pleaded guilty to a charge of criminal trespass, will serve up to two years in the Wayne County Detention Center in Jesup, followed by eight years’ probation. He was fined $20,000 and ordered to perform 360 hours of community service.

The resolution of the most prominent Hollywood film-set death case since 1982 — when actor Vic Morrow and two child actors were killed in an on-set helicopter accident — sent shock waves through the industry.

Many “below the line” crew members, who include technical and craft workers, have long complained about a perceived cavalier attitude toward set safety by directors focused on costs and deadlines.

Though many in the industry were disappointed Miller did not get a harsher sentence, the case could have lasting repercussions for Hollywood and the way it does business. It could discourage filmmakers from skirting rules and prompt greater scrutiny of safety issues, industry experts said.

“Sometimes in the frenzy of making movies, basic common sense and rational decision-making get shunted aside. That is wrong and in this case ended up with a very tragic consequence that sadly could have been avoided,” said Joe Pichirallo, chair of the undergraduate film and television department at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, and a former studio executive.

Laurie Levenson, a professor at Loyola Law School, said, “Sometimes the only way to get people to pay attention to safety is to show them the consequences will be grave if they don’t.

“It’s almost like you have to remind every generation of filmmakers you don’t get to take this risk with people’s lives.”

The accident occurred on the historic Doctortown Railroad Trestle over the Altamaha River. The crew had placed a metal-frame bed on the tracks that actor William Hurt, playing Allman, was supposed to lie on for a dream sequence.

Lawyers for Miller had said that the company had received permission to film on the trestle from Rayonier Inc., a paper company that owns the land. Rayonier had told the film company that only two trains would be using the track that day, the lawyers said. After two trains, the crew set up for filming.

“Randall Miller at the time this happened believed there were not any more trains that would come down that track,” said Miller’s lawyer, Edward T.M. Garland.

But prosecutors had said the filmmakers knew that CSX, which owns the track, had denied them permission in writing to film on it.

The third train came hurtling toward the crew at 55 mph, scattering them as they scrambled to get off the trestle. The train struck the metal bed, sending fragments toward Jones.

Jones’ parents said they hoped that Miller’s prison sentence would send a strong message to Hollywood about film-set safety.

“We do call for the movie and television industry to examine themselves and examine the myth of this bubble of cinematic immunity they may think they have,” Richard Jones said.

In a separate interview with The Times, he added: “We were never seeking revenge. We were always seeking accountability.”

Elizabeth Jones, Sarah Jones’ mother, said, “Her death will not be in vain.”

Since their daughter’s death, the couple have worked with unions and Jones’ film industry colleagues to promote greater awareness of film-set safety and spur industry changes. Both appeared in court Monday to read statements about their daughter’s death.

Though fatal accidents have a long history in Hollywood going back to the earliest days of cinema, criminal charges against filmmakers are extremely rare because of the difficulty of proving that they acted with intent to cause harm.

The case is the first in more than 30 years in which film executives have been criminally charged with manslaughter in connection with a film-set death.

In 1982, Morrow and the two children were killed when a helicopter crashed during late-night filming of “Twilight Zone: The Movie,” near Santa Clarita. After a 10-month trial, director John Landis and four associates were acquitted in 1987 of involuntary manslaughter.

Under Miller’s plea arrangement, he is prohibited for the next 10 years from serving as a director, assistant director or in any other role with responsibility for the safety of film-set employees. He was escorted from court by a deputy and taken to the county jail to begin serving his sentence.

Garland, Miller’s lawyer, said Miller decided to plead guilty primarily because it was part of a deal to drop charges against his wife. The couple have two children, 12 and 14. “He did not want to put his wife at risk,” Garland said.

Garland added that he expected Miller to serve only a year of his sentence, followed by nine years’ probation.

Although Miller accepts full responsibility for Jones’ death, Garland said, the director was convinced the set was safe.

Garland said sending Hollywood a message about accountability and safety “has been the goal of the Jones family — and, unfortunately, our client became the vehicle for that process.”

A third defendant, executive producer Jay Sedrish, was sentenced to 10 years’ probation, to be served in California. Sedrish is also prohibited during his probation from performing film-set work in which he would have responsibility for the safety of employees.

A fourth defendant, assistant director Hillary Schwartz, was to be tried separately and had been expected to testify against the other defendants. A member of the defense team said Schwartz was expected to agree to a plea deal.

Judge Anthony L. Harrison, who said he accepted Miller’s plea deal “with some reluctance,” told Jones’ family that her death could have been prevented.

“I hope this day will in some way contribute to your goal of sending a message to the film industry regarding safety and responsibility,” the judge said.

Steven Poster, president of the International Cinematographers Guild, said he hoped the case would persuade the industry “that safety measures must be followed at all times.”

“We want all workers to exercise their rights to safety on sets,” he added.

The union already has launched an app to communicate with crews about safety issues and has worked with officials from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to improve training in states such as Georgia.

Zucchino reported from Jesup, Ga., and Verrier from Los Angeles. Times staff writers Saba Hamedy and Ryan Faughnder in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.