From the Archives: James Horner on creating a ‘sound world’

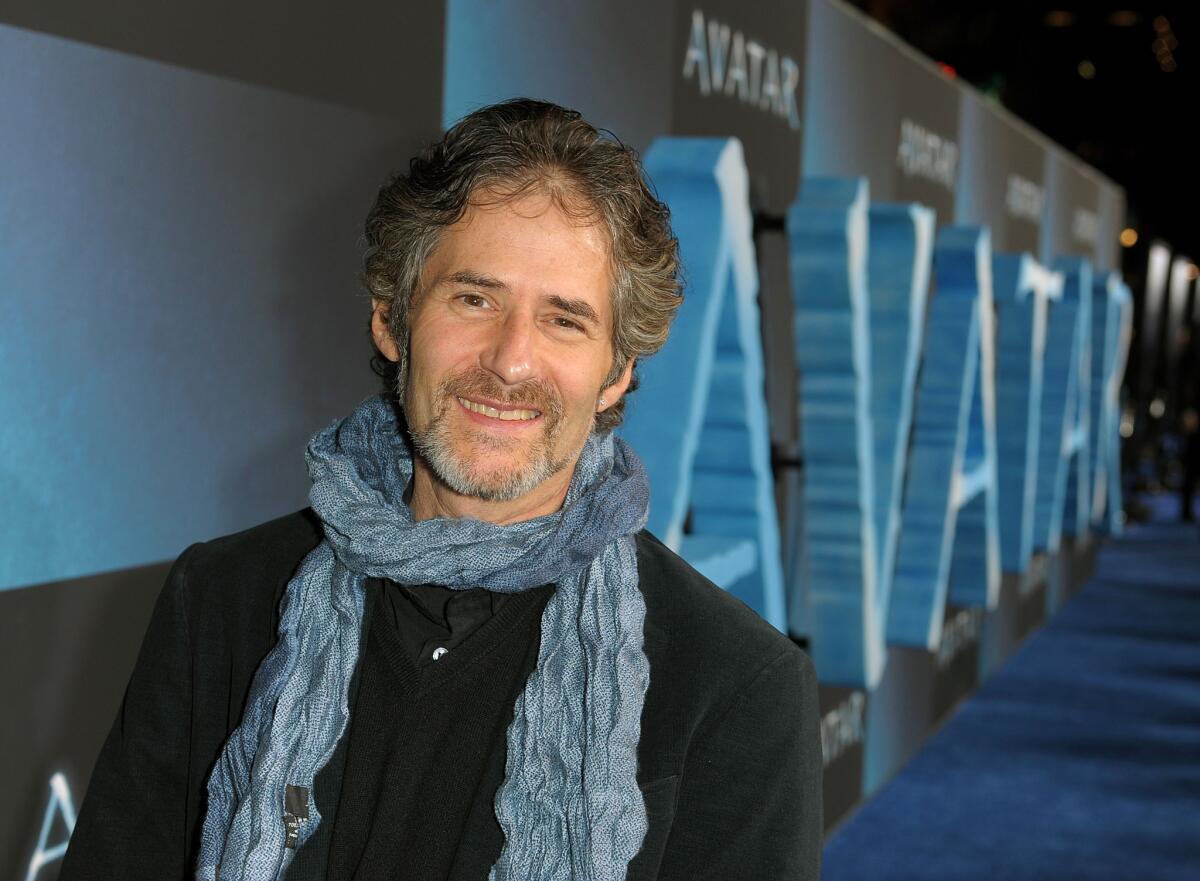

Composer James Horner at the “Avatar” premiere in Hollywood on Dec. 16, 2009.

- Share via

In 2009 we were ramping up for the elaborate and all-consuming spectacle and abstract world building that was the premiere of James Cameron’s “Avatar.” As part of our long journey toward Pandora, Hero Complex editor Geoff Boucher spoke with Oscar-winning composer James Horner, hoping to get a glimpse into his “world of sound.”

This week, Horner died when his small plane crashed in Los Padres National Forest near the border of Ventura and Santa Barbara counties. In his memory, we’re revisiting the 2009 interview that explored his work on “Avatar,” which reunited him with “Titanic” director-writer James Cameron:

As we close the door on November, our countdown coverage to the Dec. 18 release of “Avatar” continues, and it’s fascinating to see the opinions, gossip and expectations that are already putting the film front and center in the marketplace of ideas. The most expensive film ever made? Sure, probably. The most over-hyped? Possibly. Easy to ignore? Absolutely not. The game-changer? We shall see. Today we bring you the first part of our conversation with Oscar-winning composer James Horner, who famously collaborated with “Avatar” director-writer James Cameron on “Titanic.”

This film takes place on another world, a distant, troubled moon covered with lush jungles and dotted with floating mountains. That must have made for an interesting set of decisions when you began work on the score.

This film is so radically different from any other movie and, really, from any other movie ever made, both on a technical level — how it was made — and just the look of it. The usual sort of rules and the ways I would approach the project don’t apply. What was asked of me was to create a score that was grounded for a conventional audience — being that it would play in Oklahoma — yet at the same time was very adventurous in terms of the sounds I would use and the approaches I took cinematically.

There’s also the epic sweep to the film; you’ve had experience with that, certainly, with “Titanic” and films such as “Braveheart,” “Apocalypto” and “Troy,” but in each of those you had an earth-bound historical backdrop to use as a reference.

Yes, correct. The sound world that I created for “Avatar” had to be very different, really, than anything I ever created before. There is also three hours of music. I had to find a sound world that covered so much territory; it had to cover both the human side of the story and the indigenous side of the story and the tremendous, epic battles that take place as well as the love story that is at the core of the film.

How do you create a “sound world,” as you put it?

I had to create a sound world that was really quite different than anything I had used before. It wasn’t simply a matter of using instruments from New Zealand or Iceland or Lapland; I had to create new instruments, too, a whole library of instruments and sounds. I also found indigenous instruments and digitized them and changed them slightly. I used a lot of voice and digitized that to create a sound world for myself, a palette of colors so that I was able to create worlds that satisfied [James Cameron] and his need for this new world to sound appropriate as a place that you had never been to. It had to be different and alien yet at same time to have a very warm quality and an organic quality. The score needed to be very grounded, too, as I said. The score is very thematic even though the colors are very exotic.

That’s interesting about the created or altered instruments. Could you be more specific?

There were a lot of vocal sounds I took from various places. These were odd vocal sounds that I would manipulate digitally and there were interesting flutes, for instance, from South America and Finland that I wanted to be more abstract. I also have instruments invented from scratch. They were programmed. There were a lot of instruments that sound like flutes of different sorts, but they were combined with gamelan-sounding instruments. The gamelan is Balinese. The word itself means “orchestra.” The individual gamelan instruments are these bell-like sounds. A lot of the percussion for “Avatar” is gamelan-based or sounds gamelan-based. So this has this sort of quality of ringing bells, like Indonesian music. It’s a very pretty fusion of different worlds that gives the place itself a quality that is magical. Using it for percussion, rather than drums or other things, gives a sort of magical glow to everything. And as I said there were a lot of instruments that I invented and worked on with my programs. I was very particular.

That sounds like a pretty fascinating expedition for a composer. I can’t imagine there are many Hollywood projects that entail the invention of new musical instruments.

But the most important thing that came before anything was creating a sound world that would convey Pandora and the world Jim was trying to invent. It had to be foreign yet not avant-garde and not art film; it needed to support melodic writing so I could write thematically. I had to stay grounded in that way. I couldn’t go off into some weird world and present a whole new scale system or a whole new theme system; I had to try to glue everything together. The film — as radical as it looks and with the “new look” of all the information coming as you visually — required music that was grounded and emotional. No matter how dense it is on the screen or how alien it might be, there is a thread in the music that keeps it grounded for the audience so they know what is going on and how to feel.

You mentioned a magical glow to the music. One of the most striking things about Cameron’s alien setting is the iridescence and bioluminescence. Tell me how that fit into your creation of a sound world.

With how beautiful all of that looks, that has to be reflected in the music. I can’t use common instruments when I paint that; I can’t use common words to describe it. You have to make an audience experience with the ears as well as their eyes.

On the screen, Jim Cameron’s movie aspires to create a whole new world and do it with next-level visual effects and filmmaking techniques, but on the page, really, this is a very old-fashioned adventure tale. You can see flashes of “The Man Who Would be King” or “Heart of Darkness” in it and Jim Cameron has acknowledged “Dances With Wolves” and “At Play in the Fields of the Lord” as influences. It seems to me the approach you’re talking about with the score — present the fantastic but make sure that it’s grounded in classic structure — is the same approach taken with the script.

Yes, you’re right, the story is basically an ex-Marine in a wheelchair whose epic journey takes him from that point all the way to leading a nation. That whole journey has to be covered with music. There’s a tremendous amount of emotional weight that journey carries.

Part 2 of the interview was originally published on Dec. 2, 2009:

Moviegoers will finally reach the moon called Pandora on Dec. 18 when writer-director James Cameron’s “Avatar” completes its long journey to the screen. The most expensive movie ever made will make history — but what will its legacy be? Today we continue our 30-day countdown with Part 2 of our interview with Oscar-winning composer James Horner.

Do you think moviegoers will have a hard time wrapping their heads around the sci-fi elements of “Avatar”? Are you concerned that the film won’t be as accessible as, say, “Titanic,” which you worked on with James Cameron so memorably?

Within this movie, of course, importantly to me, there’s a love story. To me a love story works as a counter to all the fanboy stuff. Without it, the film is just an unbelievable visual treat and at the end of it you don’t have an emotional feeling or connection. You’ve seen epic gun battles you’ve never seen before but, in your heart, if you’re a 17-year-old girl, why would you ever go see that? My job — and it’s something I discuss with Jim all the time — is to make sure at every turn of the film it’s something the audience can feel with their heart. When we lose a character, when somebody wins, when somebody loses, when someone disappears — at all times I’m keeping track, constantly, of what the heart is supposed to be feeling. That is my primary role. I have to color all the rest, and be on top of all the details and part of all the action and paint everything with my weird colors and weird orchestra and all that, but my primary job is knowing what the heart is feeling. It’s very important that this film — although far from being a romance — doesn’t lose sight of the love story in the middle.

It’s interesting, too, that small moments become so key when a movie gets as big as this one. The machinery of the movie is so big that without successful small moments and human emotion, it could turn into a video game.

Absolutely. Yes, that’s right. And, not to mention names, but if it was Michael Bay making this movie we wouldn’t be having this conversation. These things wouldn’t matter or they certainly wouldn’t matter as much. Jim knows the importance of it not just becoming mecha. Jim knows that a movie can become swamped in just unbelievable imagery and that it becomes hollow. Jim won’t allow that and my job is to make sure it doesn’t happen.

Tell me about your working relationship with Cameron. Do you start from similar places or is it a collaboration that begins with opposing sensibilities?

He and I get into tussles sometimes when I think something should be a little bit more human or heartfelt and he thinks it’s not necessary. I’ll write a cue two different ways just to cover myself. Sometimes he will use the drier way and then, a month later, he’ll swap out the cue for the version I proposed in the first place. It’s interesting. You can’t tell what the balance is until the whole thing comes together.

I would imagine that you want to be in front of the beat or behind it, emotionally speaking, and that in some sequences the emotion is obvious but that in other instances you need to signal something to bring the scene to its fullest impact.

Exactly. That’s exactly right. And with a movie like this you don’t get the sense of it until it starts to accumulate. You see two hours of it strung together, you get a sense of the scale of the epic and scale of the relationships and the scale of the fanboyism versus the emotionalism of the film. That’s when you are able to make better decisions. That’s when you modify and reconsider things. .. there’s been a lot of fine-tuning in the last month, putting things back and adjusting things. It’s such a long film. No one can be perfect at this the first pass; there’s no hole-in-one with this sort of thing. This is a thing where certain things are easy but on the whole you need a couple of tries at it, both in editing and scoring. Some things work great right away and you know it’s perfect but a lot of it requires you to revisit.

Was there a particular segment of the film that was especially challenging or is the real labor this sharpening throughout that you’re describing?

It’s more sharpening throughout. My instincts are pretty good. I’ve done quite a lot of films now. With this one, I know the story and I know Jim. At certain times, when Jim is telling me something and what he wants, I can project that four months from that moment we will be revisiting the matter with a different result.

Does he find that charming or maddening?

He finds that intriguing. The way we handle it is I will do it his way but then I will do a second version my way. I do it because I just have this feeling that, in the overall scheme of things, that if we run it the way he is asking me to run it, it will be fanboy style. The way he is working, though, he has to be so localized in the film so that each section is perfect locally. That’s the way you have to approach a film of this scale. When you think locally, you’re not thinking globally. My approach though is thinking globally — about the whole movie, not just sections — and watching things in the long run. So there are times when I know we will revisit these things. After the local problems are long solved then we come back to the conversation about the global emotion. We’ll be back to “What are Jake and Neytiri feeling now?” “What should the heart be feeling?” “What should an audience be feeling the next morning after Jake and Neytiri spend the night together?” Those are the kind of things that are difficult to tell at the time when you are solving local problems. And you can’t project for Jim. He’s very dogmatic. But you can find an answer and put it away and then show it to him four months later.

It’s interesting, your job sounds more like sculpting than painting…

It is. It is both, really. To me, writing and composing are much more like painting, about colors and brushes; I don’t use a computer when I write and I don’t use a piano. I’m at a desk writing and it’s very broad strokes and notes as colors on a palette. I think very abstractly when I’m writing. Then as the project moves on it becomes more like sculpting.

It’s interesting to consider the fact that this is Jim Cameron’s first feature film since “Titanic.” It’s been a dozen years since we’ve had a Cameron movie premiere and that’s a surprising thing — even to distanced observers like me. Is it surprising for you as well?

Yeah, it is. He had other projects, I know, but it is surprising. He was thinking about this movie for quite a while and getting it staged and ready to go took four or five years. It is interesting but then if you think about it, it would have been really difficult, no matter how much bravura one has, to jump right from “Titanic” into another massive project. I suppose he could have done something like a small love story but Jim’s not like that. He wanted to top the previous output. And that took some time.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.