Reel China: Land of cinematic opportunity

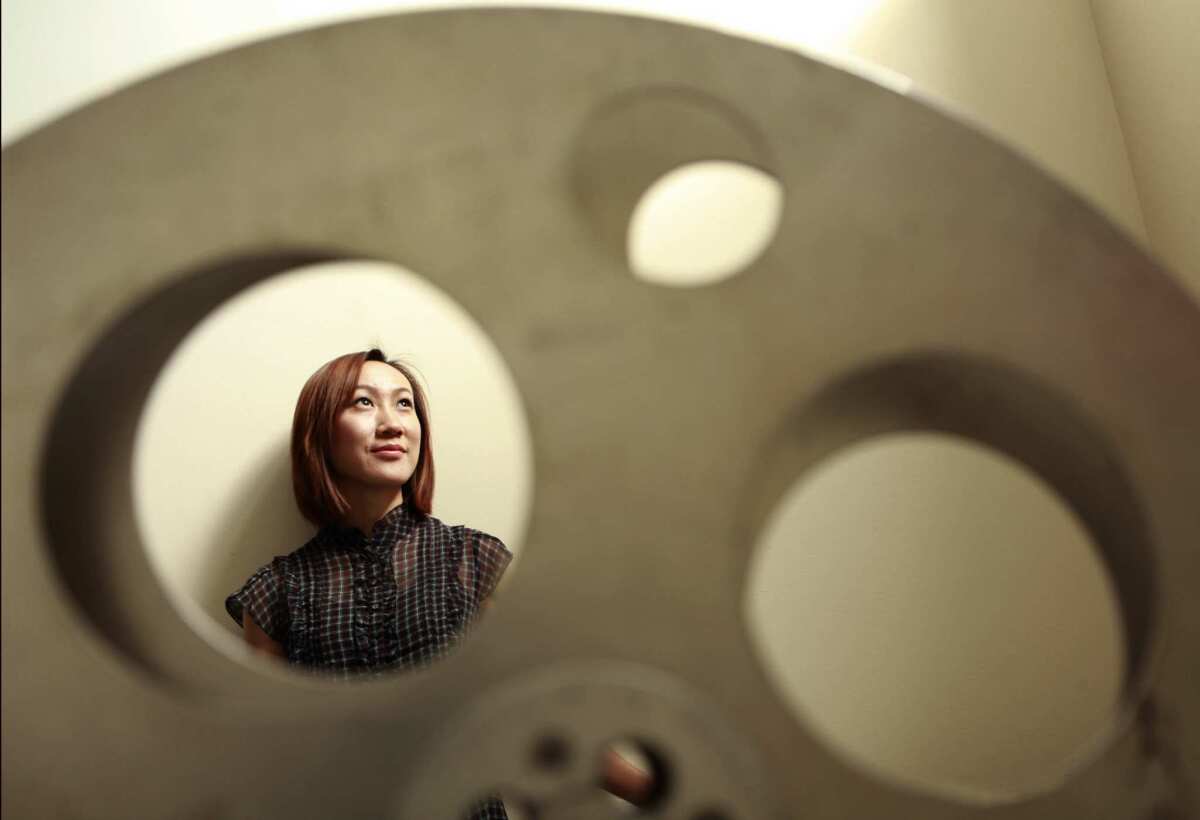

STUDENT: Sally Liu came from Beijing to get her MFA at

- Share via

Born in northern China and raised in Beijing, Sally Liu came of age in the 1990s and dreamed of becoming a filmmaker. With the world’s most populous nation swelling with thousands of new cinemas, big-budget productions proliferating and box-office grosses multiplying, the movies in China aren’t just glamorous, they’re a serious growth industry.

When it came time to apply to film school, though, Liu didn’t look to China’s most prominent institution, the Beijing Film Academy. The competition is fierce — the academy accepts only 500 students each year from among 100,000 applicants, making it about 140 times harder to attend than Harvard University.

“If I applied to a film school in China, I probably wouldn’t have gotten in,” said Liu, 28, who just completed her masters in fine art at Columbia University. “It’s super-competitive.”

Yet it isn’t just ease of admission that’s luring Liu and an increasing number of Chinese writers, directors and producers to study filmmaking at some of America’s most elite campuses. It’s also the practical curricula, creative environment and the freedom of speech.

Even if they might struggle with English, Chinese film students enrolled in U.S. institutions find that they can develop a new creative voice here, freed from government censorship and storytelling strictures that favor period epics over modern character dramas. When one film student at USC traveled back to her homeland to make a short film about her family’s emigration from China over freedom of expression concerns, Communist authorities seized her equipment, shut the production down and asked her to leave the country.

Although China has come a long way from the days when film was seen almost exclusively as a medium for propaganda, the nation’s film schools still tend to emphasize theory and history. Their American counterparts, in contrast, offer more hands-on and practical training.

“You don’t really have much of a chance to make movies in China,” said Lingxia Song, a 2006 MFA graduate in Northwestern University’s play and screenwriting program who is from Shanghai. Even if you get a shot to direct, she said, cameras, lights and editing bays are hard to come by. “You’re competing for equipment — it’s too many people in one class.”

Xue Yin, a 24-year-old from Qingdao working toward an MFA degree at the American Film Institute, said she came to the Los Angeles campus “because I wanted to learn more about how to tell stories.” Her next AFI production, a drama about Palestinian-Israeli relations, would be unthinkable where she was born. “I could never tell that story in China,” she said. “It’s very difficult for young filmmakers in China to make political films.”

Although precise numbers are hard to come by, Chinese enrollment in American film schools is clearly booming, with women making up a significant portion of the students.

For the fall class at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film and Television, graduate applications from mainland China were up about 59% from the previous year. At USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, 23 of the current graduate students are from China, and Chinese enrollment at the School of Film/Video at the California Institute of the Arts doubled from four a year ago to eight in the current academic year. Film schools at Northwestern University, Columbia University and Chapman University as well as AFI also report a steady growth in Chinese students.

“They are extremely passionate — among our most creative and hard-working students,” said Steve Anker, dean of CalArts’ film and video school.

“They bring an earnestness and wide-eyed wonder,” added Mark Harris, the head of USC’s documentary production course. “These are some of the brightest students in all of China — they have an incredible work ethic.”

The trend in U.S. film school enrollment mirrors what is happening across American higher education.

U.S. graduate schools saw applications from China grow 21% from a year ago, according to an August report by the Council of Graduate Schools. The Institute of International Education, which tracks undergraduate, graduate and non-degree programs, said last November that 127,628 Chinese students were studying in the United States, an increase of nearly 30% from 2009, as China passed India as the source of most foreign-born American college students.

Although the IIE does not break down film school attendance, it did find that overall foreign interest in fine and applied arts grew 14% last year, with nearly 3% of all Chinese students selecting that area of study (business and engineering each account for more than 20% of the fields of study chosen by Chinese students).

The steady growth of applicants presents American film schools with both opportunities — such as expanding global perspectives within their campuses, while opening doors for reciprocal visits from U.S. students to China — and practical problems, chiefly language comprehension. Chinese students wanting to study at Columbia’s film school must be interviewed over the phone to test their fluency. “We don’t take people if they don’t speak English — it’s that simple,” said Ira Deutchman, the school’s film chairman.

But the real language issue is learning Western narrative structure.

American movies are wildly popular in China; even though pirated DVDs and downloads of most Hollywood films are readily available in China, audiences still swarm multiplexes showing U.S. studio blockbusters. “Avatar” grossed more in China — in excess of $200 million — than in any other territory outside of North America.

Yet Chinese film students say that instruction about flawed heroes, fantasy settings and computerized visual effects — the very elements that pushed “Avatar” into the stratosphere — does not anchor film curricula in their country’s film schools. Professors in China, furthermore, need to be members of the Communist party “and have to watch what they say,” said Liu, the Columbia graduate. “Here, you can do whatever you want.”

That creative freedom can be intoxicating for visiting students, who typically must return to China when their student visas expire (although some, like Liu, do at least stay for internships). The disparity between the two filmmaking cultures was dramatized by what happened to Yu Gu, 27 — who was born in Chongqing but emigrated to Canada when she was 7 — who just completed her MFA at USC.

As part of a student film project, she traveled back to China to direct a story about her family’s leaving the country when she was 7, not long after the crackdown at Tiananmen Square. On the second day of production, government officials appeared out of nowhere and shut her down.

“I knew there were censors, but I didn’t know the level of government restraint that permeated all levels of society,” she said. Rather than abandon the movie entirely, Yu returned to the United States and turned the project into the documentary, “A Moth in Spring,” about her experiences with Chinese censors and the ambition of the film she wasn’t allowed to make. It has played at several film festivals.

Even as they welcome more and more Chinese students onto their campuses, American educators recognize China as a burgeoning opportunity and are trying to dispatch more U.S. students and faculty to Shanghai and Beijing.

CalArts hopes to start a joint project with the Beijing Film Academy, and has been sending current students, recent graduates and professors to work with film students on other Chinese campuses. USC’s Harris pairs seven American students with seven Chinese students to make documentary shorts together. “It’s not a colonial approach,” Harris said. “Each person has something to contribute.”

Bob Bassett, dean of Chapman’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts, said the school is hosting 10 Chinese students and is working on a program in which students would split their studies between the two countries. “The aim of the program is to do international co-productions,” Bassett said.

And Jordan Kerner, dean of the filmmaking school at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, says students in his producing program will soon start studying Mandarin because he is convinced that China is “where much of the funding for film is going to come from.”

Though U.S. films are popular in China, Chinese movies have yet to make the same kind of inroads in America. Some of the Chinese filmmakers studying here suggest that the more the two countries share in film education, the more likely it will be that Chinese movies can be made in a way that will attract American interest.

Bai Yu, who is from Beijing and earned an MFA from CalArts in 2006, said one of the best features of her American campus was the independence to craft an interdisciplinary set of courses. “You have opportunities to do self-discovery, to find out what you really like,” she said. Her instruction included copyright law and budgeting, “things that are not taught in China.”

Yu, who is also an actress and singer, is now working in Beijing, trying to bring her education to bear on potential Chinese-American co-productions. “I want to make Hollywood-style action films for the Chinese market,” the 33-year-old says. “Very few Chinese filmmakers have been trained in the United States, so they don’t know how to make those kind of movies.”

Chloe Zhao, an MFA candidate at NYU, said she’s optimistic that Chinese students returning to the mainland will help shape the future of Chinese cinema. “There’s a new generation of filmmakers — independent filmmaking is really happening,” she said. “Students who go back to China will make a huge difference. We just have more human stories to tell — a bigger sky.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.