‘The Unnamed’ by Joshua Ferris

- Share via

The Unnamed

A Novel

Joshua Ferris

Reagan Arthur/Little, Brown:

314 pp., $24.99

Everyone dies of something dreadful. This knowledge has wormed into every part of our lives -- most strikingly in our marriage ceremonies, in which we vow to love one another through sickness and health and then, later, when we make private vows about just how much illness we really want to live through. It is into this breach that Joshua Ferris takes us in his second novel, “The Unnamed.”

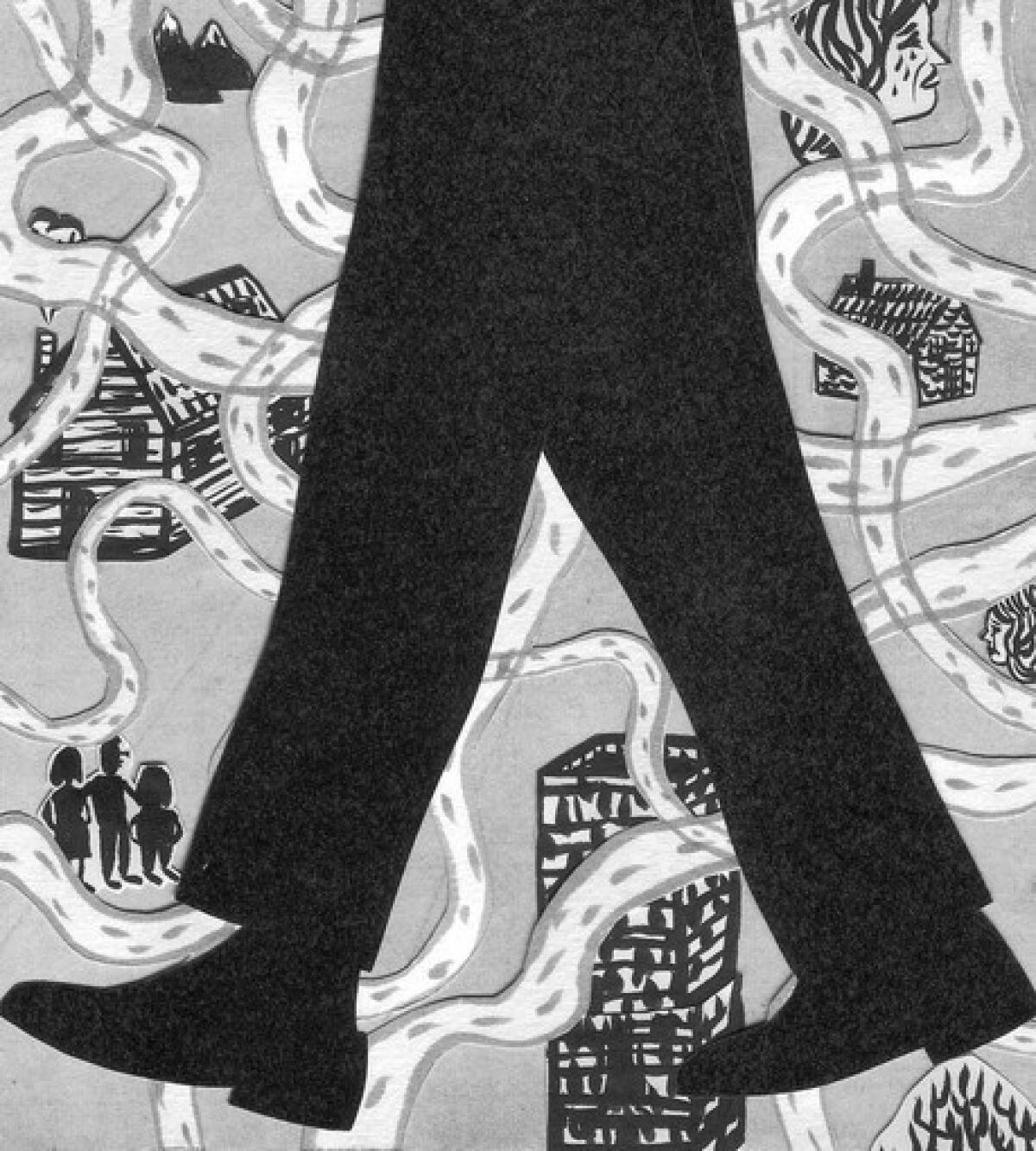

For those expecting the biting satire of “Then We Came to the End,” Ferris’ debut, this book will certainly come as a surprise. Ferris puts his notable wit and observational ability aside in favor of a far more psychological (and ultimately physical) examination of the self. Tim Farnsworth is a wildly successful partner in a high-profile legal firm in New York, the kind of firm that in a John Grisham novel might be run by the mob: In the real world, it is simply run by sharks, and Tim is more than content to spend his life sniffing for blood in the water. At home is wife Jane, a cancer survivor, and daughter Becka, your average teen. A nuclear family, in essence, except that lurking in this family is another unnamed member: the mystifying illness that has twice struck Tim with an uncontrollable need to walk until his body gives out. He then sleeps wherever he falls -- be it a ditch or a manicured lawn.

Gone for four years at the novel’s opening, the illness returns suddenly with a simple proclamation from Tim: “It’s back.” But this time, the illness is far more severe. He walks much longer distances, and the bouts recur with frightening frequency, to the point where it quickly becomes clear that Tim’s life -- and the lives of those vowing to stick with him -- is in serious jeopardy. “The health professionals suggested clinical delusion, hallucinations, even multiple personality disorder,” but Tim’s belief is far more spiritual than clinical: “Not an occult possession but a hijacking of some obscure order of the body, the frightened soul inside the runaway train of mindless matter, peering out from the conductor’s car in horror. That was him.”

All manner of attempts are made to stop Tim from walking -- chaining him to a wall, strapping him to a bed, drugging him silly -- but at some point one has to own one’s illness, or at least reckon with it and decide whether it can or will beat you. It’s madness to try to rationalize with a disorder, a sentiment Tim Farnsworth would understand acutely, since his entire life has been devoted to the letter of the law and to the idea of billable time. But time takes on a different bent when it is spent constantly in motion.

Unlike Forrest Gump, who went running, or Neddy Merrill, who went swimming in a Cheever story, the walking turns from a physical malady into a mental one as Tim finds himself “riven in two.” One-half of Tim remains the man he was, the other half is given over to the walking and decides to let this dominant self take over (though it’s not as if he has any real option). This is a key in understanding the issue of valiance that exists within this story: How much are we willing to fight if, in the end, it ruins us and those around us? In Tim’s case, his walking is destroying his wife and daughter and, of course, himself, and so the choice to let go and descend into the darkness of the illness comes to feel like altruism.

Still, it’s also certainly a psychotic break that Tim experiences, and one could argue that the walking itself is a form of schizophrenic movement disorder. But this is fiction, and Ferris has wisely made the narrative unreliable, allowing that illnesses of all stripes can be defined, but rarely does that matter since you cannot cure emotional trauma.

It’s precisely the emotional toll of Tim’s issue that reverberates throughout the novel, especially as it relates to Jane and Becka, and it also occasionally may lead to some weariness on the reader’s part as the story circles over the same basic territory several times. The odd thing, however, is that this bit of redundancy feels unremittingly true: When you’re sick, many days are precisely the same, and when you care for someone who is sick, that constancy can make you come unglued too.

“The path itself,” Ferris writes, “was one of peaks and valleys, hot and cold in equal measure, rock, sedge and rush, the coil of barbed wire around a fence post, the wind boom of passing semis, the scantness and the drift.”

“The Unnamed” is an accomplished and daring work by a writer just now realizing what he is capable of creating. Where “Then We Came to the End” chewed and gnawed at corporate life, “The Unnamed” lays bare the fabric of families, the lengths people will go for the ones they love and the lack of value we place on the simple ability to pause, to stop and to reconsider all the steps we’ve made.

Goldberg is the author of several books, including “Simplify” and, most recently, the story collection “Other Resort Cities.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.