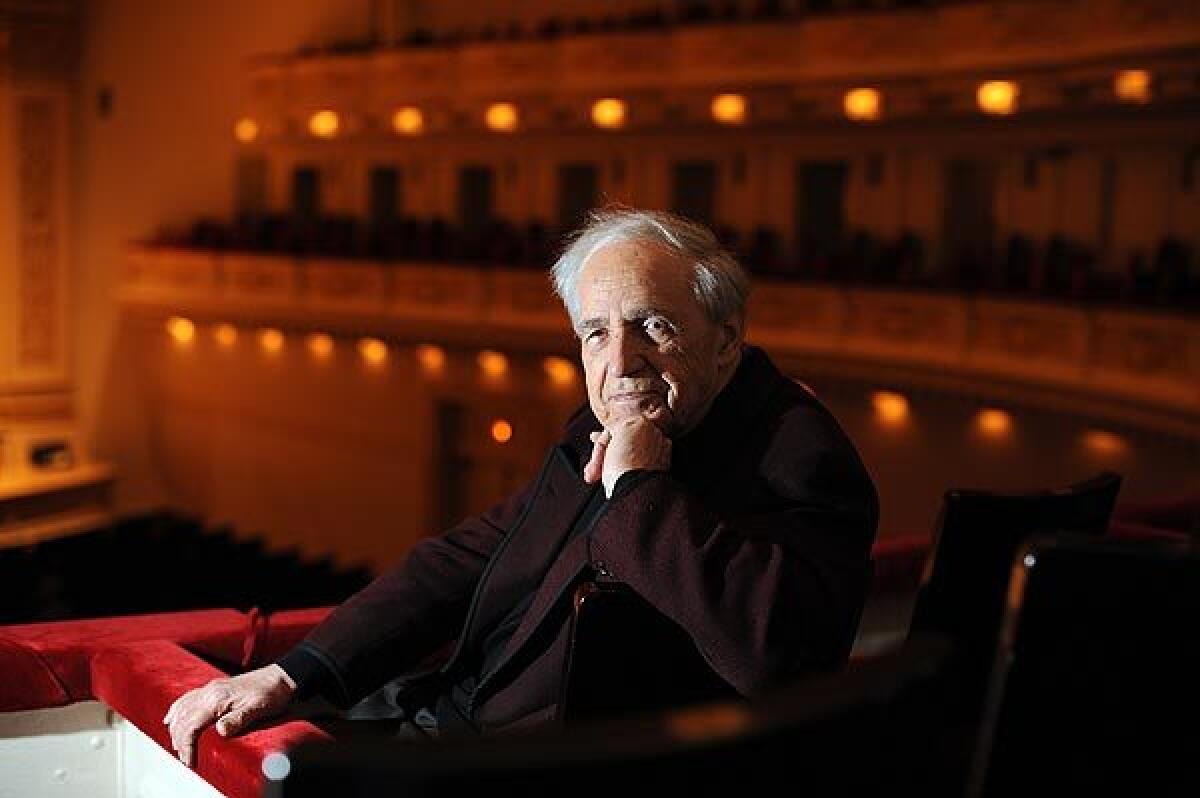

Pierre Boulez a work in progress at 85

- Share via

Reporting from New York — Pierre Boulez, everyone says, has mellowed. A half-century ago, he was famed as a maestro with a frighteningly formidable ear, a French composer of frightfully formidable music and a polarizing polemicist.

In the ‘50s, heaccused the old tonal composers of being irrelevant. In the ‘60s, he proposed blowing up old-fashioned German opera houses as an elegant solution to their hostility toward producing modern work.

FOR THE RECORD:

Pierre Boulez: An article in Arts & Books on March 21 about composer-conductor Pierre Boulez said his April 22 appearance would be at UC San Diego. It will be at the University of San Diego. —

But now Boulez is widely, warmly embraced. Having just turned 85 on Friday, he is no longer feared but feted as one of the great men of music, present and past, in a town that knows what that means. Boulez celebrated his birthday by conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in its ornate, historic home, the Austrian capital’s Musikverein. Future musicologists will no doubt mark the splendid occasion.

I met with Boulez in his hotel room in New York on a bright but freezing Sunday morning in late January. He was gracious, agreeable, witty, smart, quick, charming, self-assured, without airs. He was in good spirits and opened the blinds to let the sunshine pour in. But that hardly means he has gone soft. He has not lost his sardonic laugh. His standards are as demanding as ever. His calls for change have not changed. Boulez the progressive is still at it.

In town to conduct two concerts with the Chicago Symphony at Carnegie Hall, Boulez had also given a public talk at the Barnes & Noble store across from Lincoln Center the afternoon before I met with him. He didn’t say anything there about blowing up opera houses, although he did suggest burning libraries to the ground. But like his incendiary opera house quote (which is often repeated out of context), he also advocated rebuilding. Plus, he tends to speak in metaphors.

“History should be absorbed and rejected,” he told a motley audience, some of whom looked as though they had wandered into the bookstore to get out of the bitter cold. “If you are drowned in a library, you never have your own personality,” he continued. “Be yourself first. But that’s not easy.”

When I asked Boulez about the remark the next morning, he emphasized that going in new directions often requires building from the past. “You know, I say follow your path -- provided it goes up. That’s my definition of activity.”

Boulez, as always, remains many steps ahead of established music thinking, but some institutions are finally beginning to follow his path, and in no place is that more significant than New York. In 1971, he succeeded Leonard Bernstein at the New York Philharmonic, and his six years as music director proved as controversial as they were innovative. He built programs and seasons around themes that connected 18th and 19th century music with the 20th. He expanded his audience by holding avant-garde “rug” concerts in informal settings downtown to attract the young and unstuffy. He did what the New York Philharmonic now, nearly four decades later, is beginning to do again, if with somewhat more caution.

Boulez has had little contact with the New York Philharmonic since he left in 1977. But given the direction its new music director, Alan Gilbert, is taking the orchestra, I wondered whether Boulez might feel in some way vindicated.

“I feel that I was 40 years too early,” he answered. Back then, every time he tried to enliven the concert experience, he had a fight on his hands. “I had to confront the main critic of the New York Times, who was systematically against everything that was new,” Boulez complains. Still, he didn’t let Harold C. Schonberg, or anyone else, stop him.

Plenty of new ideas

He actively engaged the young and the hip. Understanding that Avery Fisher Hall was acoustically alienating, he wanted to bring the stage closer to the audience there to produce greater contact between musicians, which the summertime Mostly Mozart Festival has lately proved works great.

Boulez liked mixing up repertory with works that are greatly contrasted -- say, Mozart and Ligeti. And he looked for stimulating programming links around which he could build a season, pairing, for instance, Liszt and Berg or Haydn and Stravinsky. All of that sounds like it comes straight out of today’s orchestra management brainstorming sessions.

Boulez, of course, has moved on, and he has plenty of new ideas about how to make musical life matter much more than it does. He is, for instance, sick and tired of concert halls that keep what he describes as restaurant hours. You arrive in the evening at 8 and leave at 10. He wants the halls open well before concerts and well after.

And they should house media centers, where audiences can listen and learn about the music they will hear or have heard, especially when the concert involves new work. “That,” he says, “is absolutely necessary. You have to make the space interactive, where you have tools, where you can maneuver yourself, like in a science museum.”

For decades Boulez has hoped to have just such a hall in Paris -- where he makes his home -- and now one is on the way. It was designed by French architect Jean Nouvel. Yasuhisa Toyota of Walt Disney Concert Hall fame is the acoustician. “Now that President Sarkozy has said, ‘Yes, we must do that,’ the project is safe from a budget point of view,” Boulez says. But the battle isn’t over. Boulez, who estimates the hall will be open in 2014, is still taking on a Parisian musical community that opposes anything that isn’t traditional or in the center of the city.

Their arguments sound like what Boulez heard 40 years ago in New York. And with Cité de la Musique he has shown that they are as wrong today as they were then. This versatile and experimental music center for which Boulez advocated is home to new music, old music, experimental music, world music and much else. It opened in 1995 in La Villette, on the outskirts of Paris, and its opponents said no one would come. They came. It quickly became one of Paris’ liveliest venues. The new hall will be its neighbor.

If Boulez has to fight the same battles over and over, at least he is well suited for it. In fact, I can’t think of a more persistent artist ever than this composer. In 1978, shortly after returning to Paris from New York to found the high-tech IRCAM music research institute at the Centre Pompidou and the Ensemble Intercontemporain, Boulez began making orchestral expansions of some tiny piano pieces, “Notations,” he wrote in 1945 when he was 20. He is still working on them.

“It’s really an obsession now,” Boulez says. “I have composed most of ‘Notation 8,’ but I cannot finish it because of all the conducting I am doing, and you can’t bring all the paper and materials with you. I am not a slow writer, I am an interrupted writer, which is much worse.”

A robust style

Boulez’s conducting career has always interfered with his composing, and his schedule for this season would be impressive for a man half his age. On the podium Boulez appears as robust as ever. He has always liked quick tempos, and he hasn’t slowed them down. “On the contrary,” he says, “when I see lento” -- slow -- “in a score, I now realize that it is too easy to slow down in such a way that you lose continuity.” What experience has taught him is to always think ahead. “I pay attention to that more now than even before.”

But thinking ahead for Boulez also means he must, once and for all, substantially reduce his conducting schedule if he ever hopes to finish his many uncompleted works let alone fulfill new commissions. Of a violin piece, “Anthèmes 3,” he says, “poor Anne-Sophie Mutter has been waiting for five years.”

The Los Angeles Philharmonic has been after him for years to write something as well, but that is a commission he is unlikely to ever fulfill. Boulez now says he doesn’t expect to return to Los Angeles, a town with which he has a long and important history, going back to his involvement with the Monday Evening Concerts in the ‘50s, where Boulez’s most famous score, “Le Marteau Sans Maître” (The Hammer Without a Master), had its U.S. premiere. He has served repeatedly as music director of the Ojai Festival. And the L.A. Philharmonic was the first orchestra to welcome him back to the States after his New York Philharmonic years.

But given his age and schedule, Boulez finds L.A. too far to travel these days. He has a long-standing relationship with the Chicago Symphony, where he is conductor emeritus, and with Cleveland Orchestra, which was the first orchestra in America he worked with, and his future U.S. dates will be limited to those two Midwestern cities.

He does, though, have one last fling in Southern California. Boulez was awarded the Kyoto Prize last year. A Japanese version of the nobel prize given in the arts, philosophy, science and technology, it includes participation in a seminar in La Jolla. On April 22 at UC San Diego, he will speak about and conduct his chamber piece “Sur Incises” with the performers who played it with him at the Ojai Festival five years ago.

That’s another transformation of a small piano piece. In this case, “Incises” became a glittery and spectacular 37-minute work for three pianos, three harps and three percussion instruments in 1998. The process, Boulez claims, transformed his thinking about new ways to give performers freedom.

His obsession with sketches has taken him in other interesting directions as well. Recently, Boulez was asked to guest curate an exhibition at the Louvre, and he chose to examine how visual artists treat sketches.

“When you see a watercolor of Cézanne you are absolutely flabbergasted by the quality,” Boulez explains. “He did not want to show them, but he kept them.” Boulez thinks of them as perfectly finished, and he says that he is fascinated by how our perspective is influenced if you call them sketches.

Is that a rationale for why, after 65 years, Boulez still has not finished his “Notations”? Those piano miniatures are gems that no one but he would see as incomplete. But for Boulez the path must always be up, and the climb never ends.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.