Book review: ‘I Curse the River of Time’ by Per Petterson

- Share via

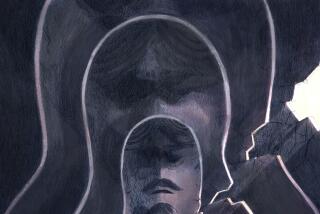

In “I Curse the River of Time,” a quiet Pietà of a novel, a mother and son try to fill in the gaps left after a life of rare communication: Plenty of love, the tough unspoken kind, but too little communication.

The mother has been married 40 years. Three sons are grown and one has died. She and her husband come and go, no longer close but full of mutual respect. She has worked in a factory for much of her adult life; has paid for the narrator of this novel, her son Arvid, to go to college. When he drops out, clutching communism as his philosophy, espousing the nobility of the factory worker, she is furious. It is a breach.

As the novel opens, Arvid is mid-divorce. His mother has just been diagnosed with stomach cancer and is going home to Denmark for further medical treatment. He follows her there, intending, what? To help her. Soon it becomes clear that he has followed her because of his own needs. He has never really grown up. He wants to tell her about his divorce.

Per Petterson is a master at writing the spaces between people. It is true, we expect this of Scandinavian literature — a report from the lands of the midnight sun, the terse but heavily-laden phrase, the decades of silence, the sorrow and regret. But Petterson, in this and other novels (“Out Stealing Horses,” “To Siberia”) shatters the caricature into a million smaller, more fascinating pieces.

This boy-man can barely reconstruct his childhood much less figure out what went wrong in his marriage. He boards a ferry in childhood, falls asleep, his life passes, and he disembarks in adulthood, not knowing where he is or how he got there. Like many children, he feels his mother did not know him: “She saw me go out and didn’t know where I was going, how adrift I was, how sixteen I was without her, how seventeen, how eighteen, how desperately walking along Trondhjemsveien I was.” This feeling of not being known, of needing to be known to know oneself is so hard to capture. Petterson does, and he’s not alone. It takes a wise translator to leave a phrase like that alone: “how desperately walking along Trondhjemsveien I was,” in spite of all the idiotic responses that are bound to follow.

Petterson assumes we will follow as he leaps from mood to mood, childhood to adulthood, innocence to crisis. Who am I? Who was I? this man wonders: “I closed my eyes and buried my hands in the sand, and I just wanted to sit here and then I suddenly knew that familiar scent, and I felt the air on my skin …but never like when I was seven years old, even though everything was different then, the season was different, the whole beach was different, no reeds or scrub back then, everything more horizontal, one line behind another, again and again, right out to the last line, where the clouds tumbled like smoke.”

Here’s the best part about Petterson’s writing: Can you feel the sea in that last passage? The rocking, unstable, predictable and unpredictable ocean? It is everywhere in the shape and movement of the novel, in the son’s doubt, in the relationship of mother and son. The author can hardly help it: It’s in every chapter, every sentence. In this watery state, this cadence, Petterson’s characters feel weather and changes in their lives — the “divorce that came closer with each day, quietly swooping like an owl through the night.” The son hopes against hope that his words could “build a bridge from my heart to hers.”

Petterson holds his characters back; they cannot triumph, certainly not with mere language. “I was searching for something very important, a very special thing, but no matter how hard I tried, I could not find it. I pulled some straws from a cluster of marram grass, stuffed them in my mouth and started chewing. They were hard and they cut my tongue, and I took more, a fistful almost, and put them in my mouth and chewed them while I sat there, waiting for my mother to stand up and come to me.”

Salter Reynolds is a writer in Los Angeles.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.