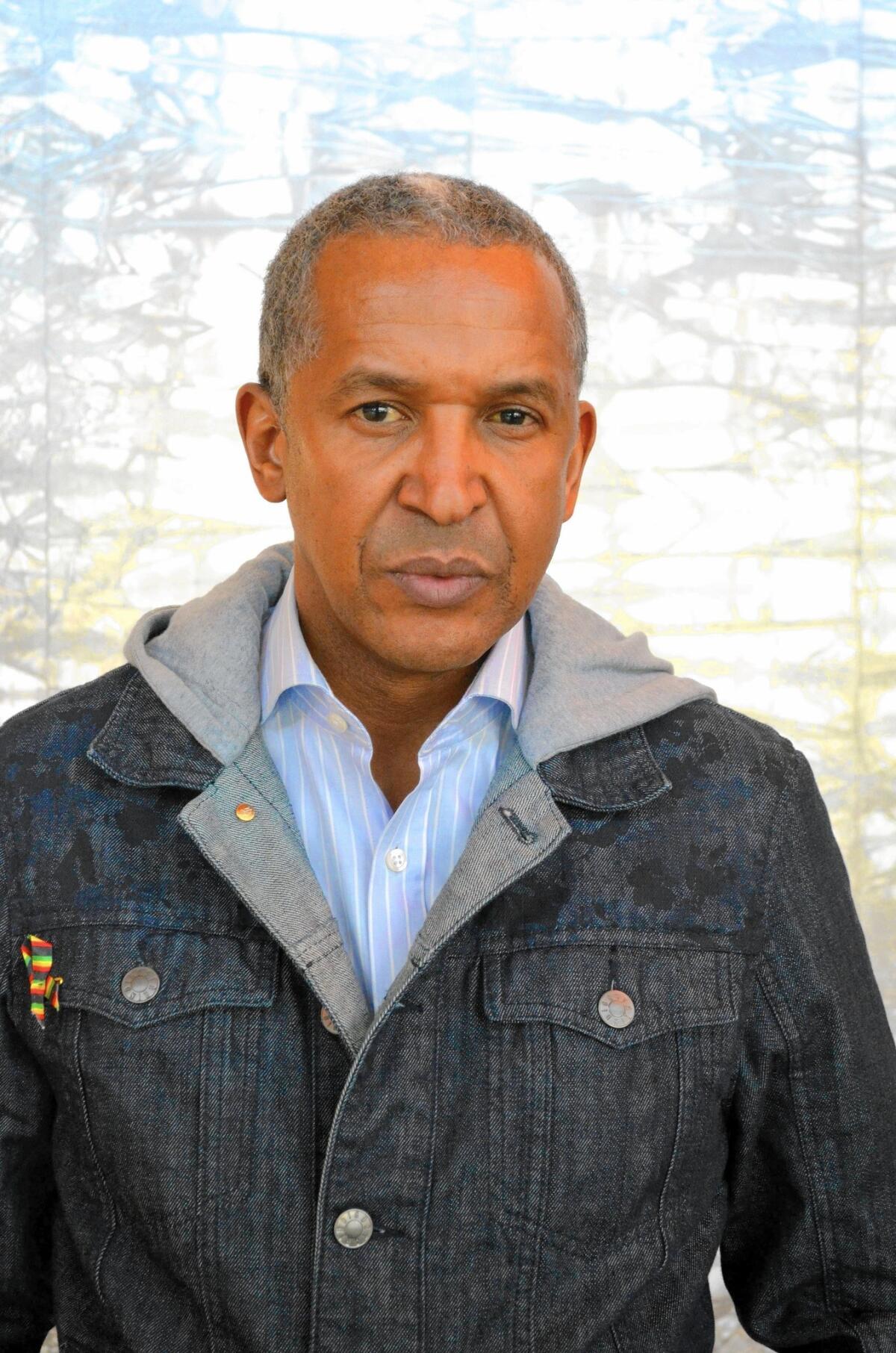

‘Timbuktu’ director Abderrahmane Sissako shines a light on extremism

- Share via

Filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako admits he was naive to think he could shoot his award-winning drama “Timbuktu” in the ancient Mali city so soon after the French military had driven out Islamic extremists.

“I first went to Timbuktu to prepare and work on my script,” said the Mauritanian-French filmmaker, 53, by phone from Paris last week.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

“Timbuktu”: A Feb. 2 Calendar section profile of “Timbuktu” director Abderrahmane Sissako misidentified the location of Oualata. The town is in Mauritania, not Mali. —

------------

A month after his first visit, Sissako returned to Timbuktu with his team and a few crew members to start prepping.

“On our way, there was a suicide bombing on the road,” said Sissako through an interpreter. “There were victims. Looking back, it was a bit adventurous of me to think that so shortly after the city was liberated, it was peaceful enough to go there and shoot.”

“Timbuktu,” which opened in Los Angeles on Friday, is an Oscar-nominated foreign language film, representing the African country of Mauritania. Last May, it won both the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury and the François Chalais Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and last week it earned eight nominations for César Awards, France’s equivalent of Academy Awards.

Times film critic Betsy Sharkey found the film “intriguingly unorthodox” and “a provocative, sometimes satiric drama about the sort of Islamic extremists who make life, especially in the outer reaches, so treacherous these days.”

The impetus for making “Timbuktu,” co-written by Sissako and Kessen Tall, was not the occupation that began in 2012 in the city but a short article Sissako read about an unmarried couple — parents of two small children — who were stoned to death that year in the small occupied Mali city of Aguelhok.

“When I read it in the press, it was just a few words about the event,” said Sissako, born in Mauritania but raised primarily in Mali, the birthplace of his father. “There was a form of indifference toward this news.”

The reason, he believes, is that “people seem to need to identify with the victim in order to make relevant news.” Unfortunately, he added, Western mainstream media couldn’t identify with the death of this couple from a small African village.

“As a filmmaker, my role is to witness such facts and talk about what touches me in that way,” noted Sissako, whose previous films include 2002’s “Waiting for Happiness.”

He feels it’s very important that this movie is “presented in front of American audiences so that audiences can talk about it and learn about it.”

The extremists in “Timbuktu” are thugs much in the vein of the vicious bandits in Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 classic “The Seven Samurai.” In the film, their edicts in the name of Islam become more threatening and suffocating. Women must wear gloves. Soccer is outlawed, as is music. Young women are kidnapped, raped and forced into marriage. Citizens who disobey risk being lashed, shot or stoned to death.

The horrors of the town are contrasted with the world of a gentle cattleman, who lives a nomadic life in a tent in the desert with his wife, young daughter and a young herder. Though they are spared from the violence and oppression of the city, their lives are tragically changed by a twist of fate.

Timbuktu held great symbolic importance for the rebels who later occupied two other Mali cities, noted Sissako. “It was important for them to take Timbuktu first because it is an open, culturally peaceful city representing the religious values of peace and love.”

Not only were citizens’ rights and liberties destroyed during the yearlong occupation, so were the city’s ancient artifacts including manuscripts.

Sissako initially went to Timbuktu shortly after the city was liberated to talk to as “many people as possible to make sure my script was as faithful to the truth as possible.”

During that visit, he met with many young women who had been forced into marriage. “The worst of it was they had been raped,” he said. “They were very young. I wanted to be very respectful and listen and show them I cared.”

After the suicide bombing in Timbuktu, Sissako moved production to Oualata in Mauritania. “It’s sort of a twin city of Timbuktu,” he said. “They are both from the 12th century. We shot there with the help of the military.”

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Feb. 2, 12:26 p.m.: An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to Oualata as a city in Mali. It is in Mauritania.

------------

But it was still dangerous.

“Though there was not a real possibility of any kidnapping, there was still a possibility of suicide bombings,” he said. “It was at times difficult to think about that.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.