Cannes 2013: Chile’s onetime cult king still the wizard of weird

- Share via

CANNES, France — The Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky has made only seven features in his nearly half-century career, but his legendary midnight movie “El Topo,” a wigged-out peyote western that played to New York audiences for months in 1970, sealed his place in the annals of cult cinema.

Jodorowsky last made a comeback in 1989 with the Oedipal melodrama “Santa Sangre,” about a serial killer operating under the spell of his armless mother. When that project was announced at the Cannes Film Festival, a journalist wondered if a decade-long break from filmmaking had left Jodorowsky rusty. He responded: “A rusty knife is twice as deadly.”

CHEAT SHEET: Cannes Film Festival 2013

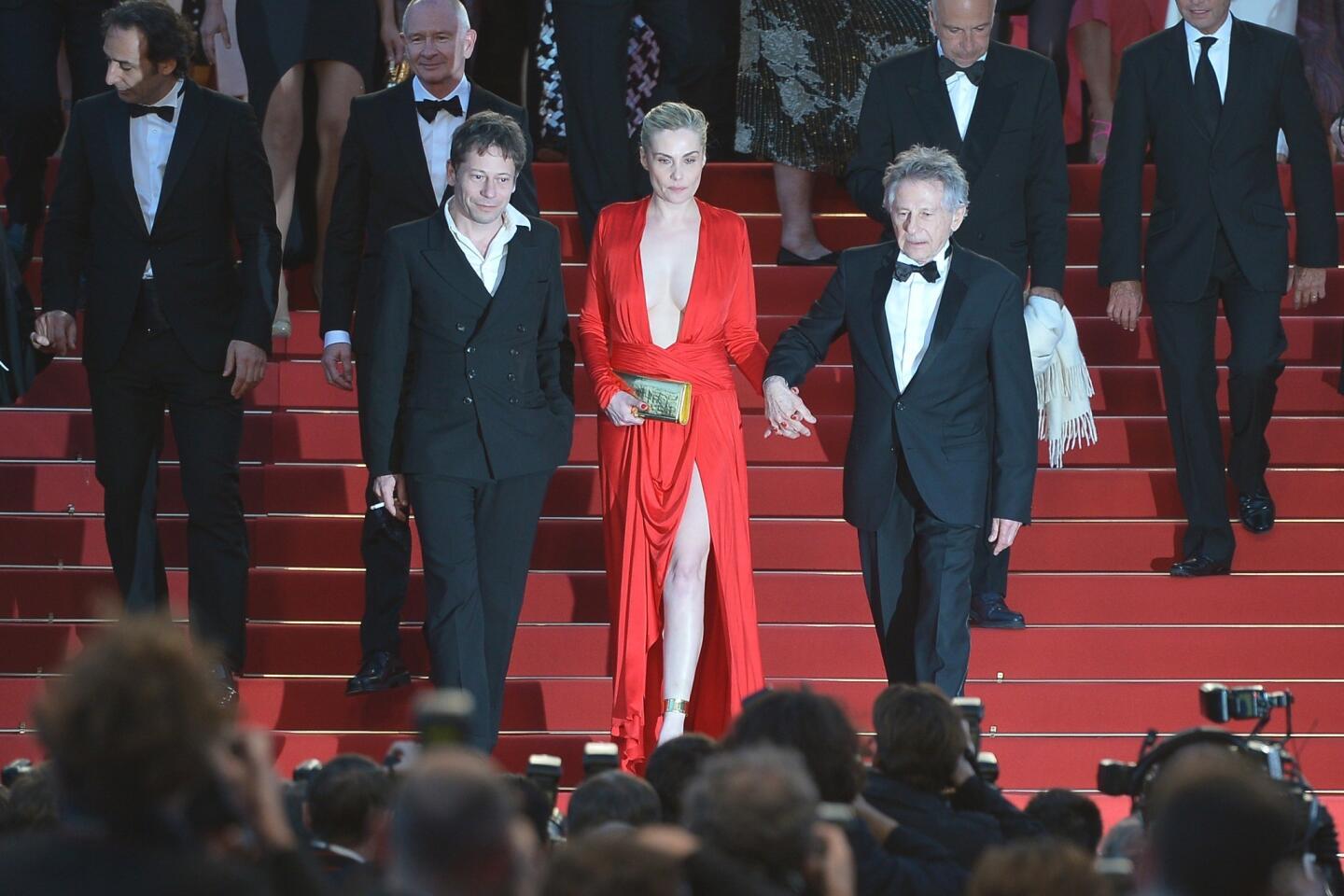

Deadlier than ever, presumably, after an even longer absence, Jodorowsky, 84, has returned to directing with “The Dance of Reality,” his first movie since 1990’s “The Rainbow Thief” (a work-for-hire with Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif that he has since disowned). Billed as a work of “imaginary autobiography,” “The Dance of Reality” is among the most eagerly anticipated titles in this year’s Director’s Fortnight section at Cannes, which is also screening “Jodorowsky’s Dune,” a documentary by Frank Pavich about Jodorowksy’s fabled, doomed attempt in the mid-1970s to turn Frank Herbert’s classic science-fiction novel into a big-screen space opera.

“Every one of my pictures is different — I die and I’m reborn with each one,” Jodorowsky said last week by Skype from Nice, where he was on vacation, preparing for the Cannes maelstrom. Even over a spotty connection, the bearded Jodorowsky, with his shock of white hair and gleaming row of improbably perfect teeth, registered as larger than life. An expansive if rambling conversationalist, he apologized several times for his faltering English and his penchant for digressive rants. After one vigorous diatribe — on the evils of money — he said, with a smile: “You know, you are speaking with a crazy person.”

On the subject of his new film, which will have its first screening May 18 (along with Pavich’s documentary), Jodorowsky declined to get into specifics. “I am like a mother with a son in my belly,” he said. “I don’t want to think about it before the baby is born.”

Jodorowsky described “The Dance of Reality,” which he shot in his hometown of Tocopilla in the Chilean desert, as “psychological time travel,” an attempt to give poetic yet concrete form to the first chapters of his colorful life.

Born to Russian Jewish émigrés in 1929, Jodorowsky studied theater and worked as a circus clown and puppeteer in Santiago. In postwar Paris he performed mime with Marcel Marceau and fell in with the surrealists. He then moved to Mexico, where he mounted dozens of plays inspired by Antonin Artaud’s theater of cruelty. Back in Paris, where he has lived since the 1980s, he cultivated multiple sidelines: writing comic books, studying the tarot and developing a therapeutic method known as psychomagic, rooted in both psychoanalysis and shamanism.

Psychomagic is the guiding philosophy of “The Dance of Reality,” a kind of home movie writ large. Jodorowsky’s wife, Pascale Montandon, was the costume designer, and three of his sons appear in it, including Brontis (who in “El Topo” portrayed the son of the title character, a gunslinger known as “the mole” and played by Alejandro Jodorowsky). In the new film, Brontis, now 50, plays Jodorowsky’s Stalin-lookalike father, whom the director described as “a very terrible father, a very hard man, but he had his reasons.”

“Before we started, I said to the crew, ‘I am trying to heal my soul,’” Jodorowsky said. “But it’s not an egocentric, narcissistic picture. Poetry doesn’t speak about history. It speaks about interior life, universal problems.”

“The Dance of Reality” came about when Jodorowsky reconnected with the producer Michel Seydoux through Pavich’s film on “Dune.” They had not spoken in years, each nursing his wounds from the abortive project, which was to have starred Orson Welles and Mick Jagger and featured a Pink Floyd score. David Lynch eventually brought Herbert’s book to the screen in 1984, but Jodorowsky’s unmade version has exerted its own influence — not least thanks to his would-be collaborators, who included artist H.R. Giger, cartoonist Jean “Moebius” Giraud and screenwriter Dan O’Bannon, all of whom worked on Ridley Scott’s “Alien.”

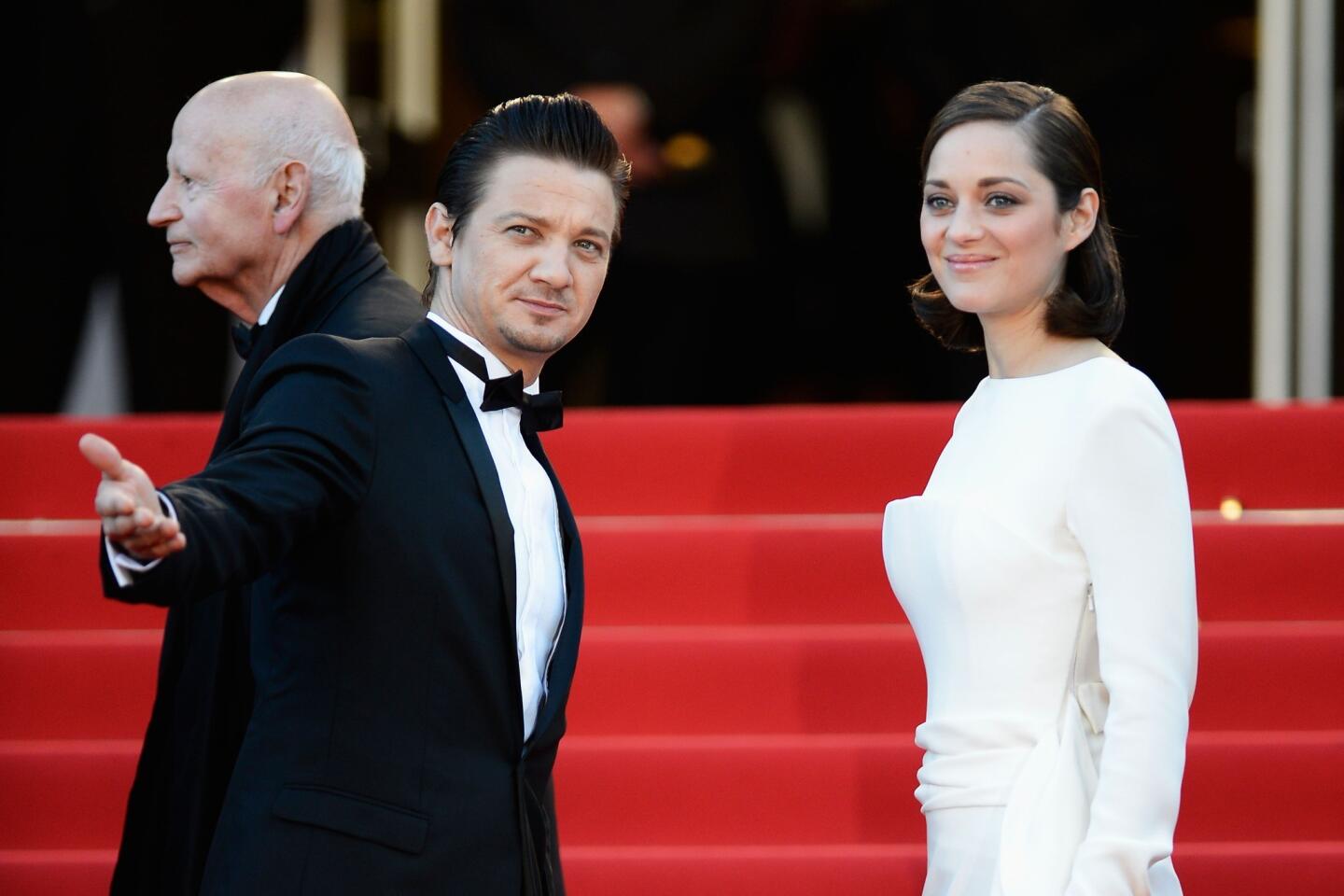

Nicolas Winding Refn, a fan of Jodorowsky’s who dedicated “Drive” to him (and is back in Cannes this year with “Only God Forgives”), appears in the documentary to make the provocative suggestion that had Jodorowsky’s “Dune” been made — and been a hit instead of “Star Wars” — it could have changed the course of mainstream cinema.

Unrealized projects loom over Jodorowsky’s career, among them an “El Topo” sequel and a gangster film, “King Shot,” that was to have starred Nick Nolte and Marilyn Manson. The money men inevitably pulled out for the same reasons, Jodorowsky said: “They’re afraid, they think it’s too surrealist, too weird.”

Jodorowsky, by his admission, is not his own best salesman. For “The Dance of Reality,” he said, “I told the producer, ‘I want to make a picture to lose money.’ I am tired of all that money. Movies are an art, not a business.”

Jodorowsky once argued that “head” movies should not merely simulate psychedelic visions — they should supplant the need for drugs. These days his musings on the power of cinema have a more spiritual bent. “I ask to movies everything I can ask to a sacred book: Bible, Koran, Torah,” he said.

“Movies were the hope of human culture. The Surrealists thought it was the real new art of the century, but now it’s the worst. The first illness is the producer, and the second illness is stars. They kill the art, the big, big egos who believe in nothing.” He’s also no fan of digital technology, which creates “scientific images, very clear, with color like a painting,” he said. “You see a tiger in a film and you have no emotion because you know it is not real. You admire the technique but you don’t believe there is any danger.”

In the Jodorowsky universe, to make art is to risk something, whether it be safety, sanity or ridicule. He shot “Santa Sangre” in actual slums and red-light districts, working with real-life criminals. On the new film, the production had to contend with extreme pollution from the local copper mines. “Everything is poison there,” he said. “After two months we were all ill.”

A onetime emblem of the counterculture, Jodorowsky is now, in his way, an elder statesman. “Fando y Lis” (1967), his violent first film, prompted a riot at its Acapulco premiere, but “El Topo” and the even more outrageous “Holy Mountain” (1973), both newly restored, have found appreciative younger audiences; the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented a retrospective of his work two years ago.

To hear him tell it, though, Jodorowsky’s troublemaking days may not be behind him. “Wait until you see my new picture — maybe that will destroy everything,” he said with a laugh. “I believe 100% in what I did, but this film is not similar to the past. It’s a step into nothingness.”

An autobiographical work by an octogenarian, “The Dance of Reality” begs to be read as a culminating work, but Jodorowksy refuses to think of it as a swan song. “People are prejudiced about my age,” he said. “They think you become an idiot. But to have more years is to become more wise. They say I am old, but to me 84 is young. I think I can make four or five more pictures. I am not in a hurry.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.