Critic’s Notebook: An appreciation: Cinematographer Gordon Willis

- Share via

When I think of cinematographer Gordon Willis, I think of “Manhattan,” one of his signature efforts. Working with director Woody Allen, as he would do so many times, they drenched the city in such exquisite light and shadows that you can stop the film on almost any frame and be stunned by the artistry in the composition of that moving picture made still.

Quintessential New Yorkers both — Willis born in Queens, Allen in Brooklyn — they treated “Manhattan” like a wanton woman, something to be desired, appreciated but never trusted. That is the way Willis made the pictures speak. Indeed, his way of translating a director’s vision made the films he shot feel of a piece, with each piece distinctive from the next.

Willis must have been, I think, a muse of sorts for the directors he worked with. Whether it was the consistency of his artistry, or some other quality, many of them returned to the well again and again. For more than a decade, Willis seemed to be primarily in the Woody Allen business. It began with “Annie Hall” in 1977, one of the airiest films the DP would shoot, and ended seven films later with “The Purple Rose of Cairo” in 1985.

There were other artistic collaborators in his life, though shooting “The Godfather” trilogy for Francis Ford Coppola, that modern masterpiece on crime bosses, has to be one of the highs. He did a modern romance with James Bridges, 1985’s “Perfect.” Then a dissolute writer in “Bright Lights, Big City” with him a few years later.

The director of photography would work constantly, mostly in film, starting in 1970 with “End of the Road,” a drama about an insane asylum run by James Earl Jones’ character. His final film, 1997’s “The Devil’s Own,” reteamed him with another longtime collaborator, director Alan J. Pakula. They did their best work together earlier — “Klute” in 1971 and “All the President’s Men” in 1976 forever etched in my memory.

Whether Willis was drawn to the projects for the directors, or the story, or to keep honing the craft he clearly loved, he tended to gravitate to the dark side. Even when it came to comedies. Take “Little Murders,” for example. Alan Arkin directed the adaptation of the Jules Feiffer play, Elliott Gould starred, the romance unfolded against a backdrop of a string of shootings. Once again, Manhattan got its share of beauty shots.

As good as Willis was at cityscapes, he knew how to let the lens savor a face, how to make the most of an actor’s particular bone structure, how long to linger on the eyes.

I was reminded of that gift in thinking of another Allen project Willis worked on, “Interiors.” It still stands for me as one of Allen’s best examinations of a deconstructing family. Like “Manhattan,” you can freeze almost any frame, but this time choose a face, any of them will do: Diane Keaton, Geraldine Page, Mary Beth Hurt, Kristin Griffith, E.G. Marshall, Maureen Stapleton, each an individual portrait of pain. In the pause you can almost sense the actors deciding how much their character can bear and how to make that real.

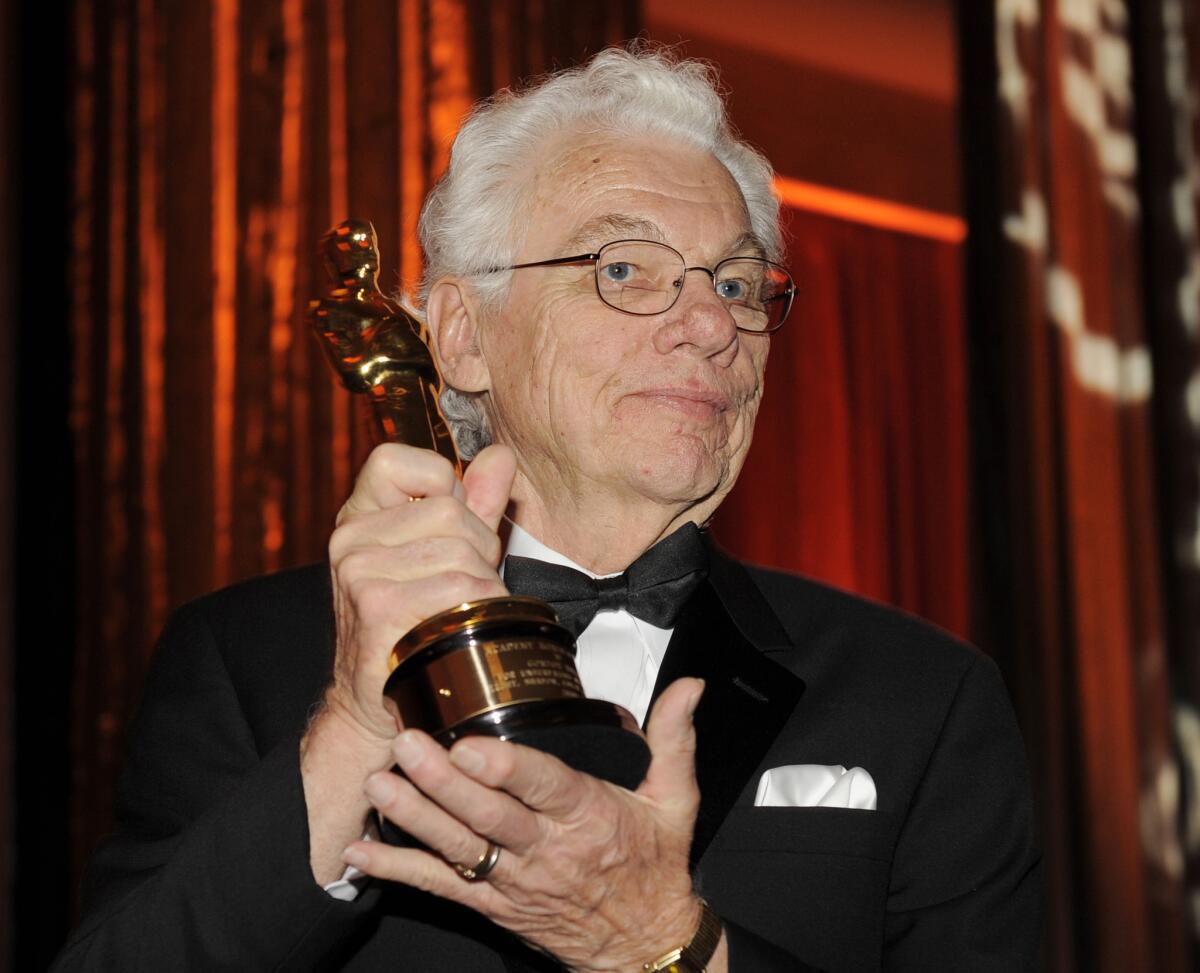

What remains the most surprising thing about Willis’ career, one peppered by great films, is that he never won an Oscar. That oversight was somewhat corrected in 2009 when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences presented him its Governors Award. By then Willis had already wrapped his legacy. The films, yes, but more — a master class on light and shadows in every frame.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.