Commentary: Is Chris Brown the victim of a double standard?

- Share via

Hosting the Independent Spirit Awards in February, comedian Seth Rogen took a swipe at both pop singer Chris Brown and the Grammys, passing it off as biting social commentary.

“At the Grammys,” he quipped, “you can literally beat the … out of a nominee and be asked to perform twice.”

Admittedly, Brown has made himself an easy target: In February 2009, he assaulted then-girlfriend Rihanna the day of the Grammys show, at which he was supposed to perform and she was a nominee, leaving her bloodied and bruised. He was sentenced to five years’ probation and six months of community service, which he has since completed.

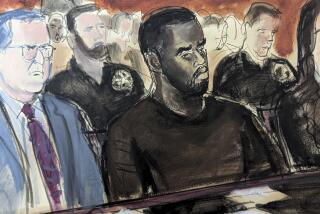

PHOTOS: A look at celebrity abuse accusations

At Rogen’s remark, the crowd at the Spirit Awards erupted in applause. Twitter nearly went into meltdown trying to keep up with all the cyber high-fives transmitted. The reaction showed that the public, evidently unlike the programmers of the Grammy Awards show, weren’t ready to forget Brown’s violent behavior.

But why does Brown continue to be dogged by his violent outburst when others are apparently forgiven?

The dart thrown at Chris Brown, for instance, could just as easily have been aimed at Glen Campbell, who appeared at the 2012 Grammys, but in the role of beloved elder statesmen. Battling Alzheimer’s and in the midst of a farewell tour, he received a sentimental embrace by the audience, who upheld him as a music icon and cultural exemplar.

PHOTOS: A look at celebrity abuse accusations

But in her 1997 autobiography “Nickel Dreams”, singer Tanya Tucker alleged that physical abuse was a staple of her brief early ’80s affair with Campbell, when he was 42 and she was 21, with the violence often playing out in front of others.

Here’s what she wrote of one especially brutal episode: “[F]inally Glen reared back his arm and brought his elbow down in my face, shearing off my two front teeth right at the roots.... I reached my hand up and felt my mouth, and there was a gaping hole where my teeth should have been.... I was without front teeth for a week, and from that time on.”

Although Campbell denied Tucker’s claims and was never prosecuted, he had discussed their stormy relationship in his own autobiography published three years earlier, “Rhinestone Cowboy,” where he wrote, “We even fought during sex once or twice.”

Not before, during or after the Grammys did anyone say a word about Campbell’s alleged abusive past or suggest that he should not be allowed onstage because of it. Then why Chris Brown? Because it’s recent? Because, unlike Campbell, he was prosecuted? Because Brown is his own worst enemy, prolonging the controversy with his behavior and his songs?

Or is it because Chris Brown is black? Bringing race into the equation will elicit groans, but the idea can’t be summarily dismissed. The Chris Brown-Rihanna episode brings to mind a similar scenario that derailed the reputation of rock ’n’ roll forefather Ike Turner, who was pilloried for his abusive behavior toward former wife Tina Turner, allegations that he denied.

Ike’s violence was outlined in Tina Turner’s 1986 autobiography “I, Tina,” a bestseller that penetrated popular consciousness in a way the country stars’ confessionals did not. Tina Turner was the ruling queen of pop when her book dropped and had secured iconic status by the time it was turned into the hit 1993 film “What’s Love Got to Do With It,” which disseminated the story on a scale the book never could have. Though he was never prosecuted for the abuse, Ike Turner’s reputation was decimated after the book came out, and he returned to form with two well-received albums only a few years before he died in 2007.

PHOTOS: A look at celebrity abuse accusations

It’s a given that Turner would never have been as warmly embraced as Campbell if he’d appeared on the Grammys. Is there a double standard? There seems to be similar discrepancies when you look at the world of actors.

If you Google the words “Charlie Sheen” and “domestic violence,” the Internet gently weeps. Yet Sheen’s well-documented fisticuffs-on-females (restraining orders from ex-wives; allegations from girlfriends and sex workers, alike, that he battered them) have not resulted in his name being synonymous with domestic violence except in an excusatory wink-and-nudge kind of way. A snickering humor trails his persona, as demonstrated in a “Comedy Central Roast” in his honor last year, where a lot of the night’s humor hinged on his out-of-control rep.

Imagine the outcry if Brown made light of his public persona the way Sheen does with his new TV series “Anger Management.”

“Historically and today,” says professor Tamara K. Nopper, sociology lecturer in race and ethnic relations at the University of Pennsylvania, “it is presumed that black people are by nature a violent people and thus they get dealt with quite differently than when non-blacks engage in violent acts.

“The level of intensity and the degree of vigilance that celebrities and some in the general public show towards Brown is less about a concern for a black woman experiencing violence as it is a general obsession with and policing of what people assume to be the inherently criminal nature of black people in general.”

This is not an apology for Brown, who almost weekly makes the case that he is in need of some sort of intervention. Brown’s latest album, “Fortune,” which dropped Tuesday, comes on the heels of new controversies involving the singer. Mere weeks ago, his entourage got into a headline-grabbing brawl with singer Drake’s camp in a New York nightclub, reportedly over Rihanna, who dated both men.

Lyrics on the May-released track “Theraflu” (Brown’s freestyle over the Kanye West track of the same name) led to widespread speculation that they were about Rihanna. Brown raps of a woman he used to be with: “Every industry … done had her / Trick or treat like a pumpkin just to smash her....” Rihanna apparently agreed with the consensus, unfollowing Brown on Twitter right after the track dropped and responding with the tweet, “Aw, poor dat #neaux1currr.”

Celebrities, the media and domestic violence activists have demonstrated, however, that they’d rather pile on than actually take advantage of the teachable moment.

In interviews, Brown, who was 19 when he assaulted Rihanna, has said his mother suffered violence at the hands of his stepfather. In a 2007 interview with Giant magazine, he’s quoted as saying, “He used to hit my mom.... He made me terrified all the time, terrified like I had to pee on myself. I remember one night he made her nose bleed. I was crying and thinking, ‘I’m just gonna go crazy on him one day.... ’ I hate him to this day.”

Brown’s stepfather, Donnelle Hawkins, has repeatedly denied these allegations in interviews and has said Brown needed to take responsibility for his actions.

Rather than have a big-platform conversation about the myriad ways domestic violence affects not just women and young girls but also the young boys who witness it, Brown’s one-note detractors have instead taken the easy tack of mocking him.

Buried is the chance to discuss how some boys who watch their mothers being abused might well take their own terror, and their shame at being impotent to save their mother, and replicate violence on the women in their own lives, having subconsciously learned contempt of women. Brown’s well-documented rage issues may be attributable to his childhood, says cultural critic and activist Kenyon Farrow.

“Chris Brown grew up in a very violent household, and in many ways, seems to be replaying the violence he witnessed his mother suffering,” says Farrow. “He’s clearly very angry and has some trauma to work through. It’s sad that his handlers seem more interested in preserving his career than getting him some mental health treatment to break this cycle of violence.”

That’s not to excuse his actions as an adult, or to argue that black men should be given the same passes as their white brethren. And, as cultural critic Greg Tate points out, for a long time it appeared that Brown would actually get such a pass.

“The thing with Chris,” says Tate, “is that he was already getting his pass [until] social media posted [Rihanna’s] horrifying post-beat-down face shot. Even [after the photo surfaced], crazy numbers of young, educated black and Latino women, on and off line, were documented expressing zero sympathy for Ri.”

The Chris Brown-Rihanna story is caught in two social currents: There is the decades-long battle to have violence against women taken seriously by both law enforcement and the culture at large, but there is also the American cultural reflex to demonize black men while covertly sanctioning ill-doings by white men.

“The treatment of Chris Brown,” says Nopper, “suggests that many don’t think a black man who committed violence against a woman can be rehabilitated, which continues a long-standing American tradition of anti-black racism.”

In truth, Chris Brown is more a cautionary tale ripe for a more nuanced reading than he is a monster, even if he insists on stoking his own bad rep and writing — with assistance — his own tragedy.

ALSO:

Reviews: Chris Brown’s ‘Fortune’ is brash and commercial

Chris Brown hints at retirement, wins top R&B prize

When digital beef gets real: What Drake, Chris Brown, Meek Mill can learn

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.