Critic’s Notebook: Kinks’ Ray Davies is turning 70. Why it matters.

- Share via

Saturday is Ray Davies’ 70th birthday, but I’m not writing this as an offering or a note of congratulations.

Having bought 53 pieces of vinyl or CD plastic by the Kinks, both of his books, his two solo albums of new songs and 30-odd concert tickets, I think I’ve already thanked and celebrated him in the way he can most appreciate. I hope what I’ve paid him has given him a fraction of the enjoyment I’ve had in return.

I am not obsessive about the Kinks. I’m a musical omnivore open to excellence in any style. I’m thrilled by most of the usual suspects on the all-time greats lists of rock, soul, country, folk and blues, and by a good many more obscure artists.

But this Davies milestone seems like a good occasion to try to explain why, given my appreciation and fondness for so many songwriter-performers, I should regard him without hesitation, and by a considerable degree, to be the best.

The answer begins with my calling him the best, not the greatest. Musical greatness requires some form of dominance or gigantism, typically measured in lasting direct influence on other artists and a magnitude of personality and celebrity that makes bystanders pay attention along with true fans.

All the Kinks did, with Davies in command as frontman, predominant songwriter, producer and arranger, was create the warmest, funniest, most varied and keenly intelligent body of work in the rock canon.

His voice won’t blow casual listeners away, but it’s the perfect vehicle to get his stories across while making the most of his melodic gifts, which are second to none, the Beatles included. Davies’ oeuvre is too idiosyncratic, stylistically wide-ranging and based on rare skills of observation to attract credible imitators, as opposed to admirers.

To the extent the Kinks were influential, I think the credit belongs to Ray’s younger brother, Dave, whose manic guitar squalling drove the early sound that gave them a career in 1964.

Capturing in a vocal-band context the wildness inherited from formative roaring rock instrumentals such as Link Wray’s “Rumble” and Dick Dale’s evocations of riding big waves, the scrappy 16-year-old from North London fired away like the musket-wielding embattled farmers of Lexington and Concord, signaling the birth of a hard-rock nation.

After that it was Ray’s show, and the result can be summed up in a single proudly neurotic song title: “I’m Not Like Everybody Else.”

From the musical evidence, Davies, though certainly ambitious for commercial success, was not interested in the kind of greatness that brings dominance and influence. That is most often attained by making big statements with big themes, exuding sexual allure or authoritative cool, and personifying an audience’s aspirations to a bigger life than real-world living allows.

All Davies wanted to do was follow where his endlessly idiosyncratic imagination could take him, while the Kinks provided the broad palette of styles, colors and rocking intensities he needed to render musical pictures scaled to life’s daily realities.

He never went for the expressionism, abstraction or mysticism of a Dylan or a U2. I can’t think of a Kinks song that’s oblique or mysterious, or that gushes cascades of imagery for would-be poetic effect. “Harry Rag,” their only song about a drug other than alcohol, comically skewers the Sixties worship of toking as some kind of cultural talisman.

With Davies, a listener knows exactly who he’s singing about and what they face, including their economic circumstances. He is by far the pop songwriter who’s most conscious, in a nuanced way, of the importance of money. His characters are only occasionally desperately poor; more often they cling precariously to whatever protection and security they might have. Davies simply knows more than any of his peers about the exigencies of life on a human scale.

Consequently his characters are never heroic. They have everyday frustrations and everyday enjoyments. Multiple Kinks songs herald and chuckle over the quiet pleasures of picnics and tea time. When Davies delves into his own psyche, a listener hears him coping with loneliness and loss and disconnection from family and friends, but also struggling to find enough heart and encouragement to snap out of a funk and move forward.

It’s mainly by mood, method and implication, rather than by declaration and exhortation, that Kinks fans have learned from their non-transcendent hero that our best chances lie in humor and a simple refusal to give in to the temptation of just giving up. No one has written more songs about how hard it can be simply to get out of bed and face another day, but Davies’ characters almost always find a way to do it.

In “Celluloid Heroes,” his eloquent rock ballad about Hollywood and its stars, Davies’ point is that showbiz and stardom are valuable enchantments, but in the end the tinseled guise can’t last, even for the stars themselves. The glamour gives way as the world rushes in.

Nevertheless, there’s never been a Kinks album that was a downer. Even a song of roaring anger like “20th Century Man,” a magnificently arranged and performed piece that builds momentum from its opening acoustic tension to a blazing rock release of fear and disgust, starts with a certain bleary humor before erupting against the march of mass-retailed modern culture. Humor is Davies’ guiding spirit – for example in “Life Goes On,” whose first-person protagonist (someone not unlike the songwriter himself) is grateful and amused to recall a thwarted suicide attempt as a lucky pratfall.

Which is not to say that Davies’ vision shies from grimmer things. The two most brilliant Kinks albums, “The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society” and “Arthur,” both end on very dark notes of profound isolation or futility. “Preservation,” Davies’ rock-theater extravaganza about real estate development and rascally political corruption, has a denouement that veers from comedy to Orwellian menace as a self-righteous totalitarian supplants the rascal, who at least was recognizably human.

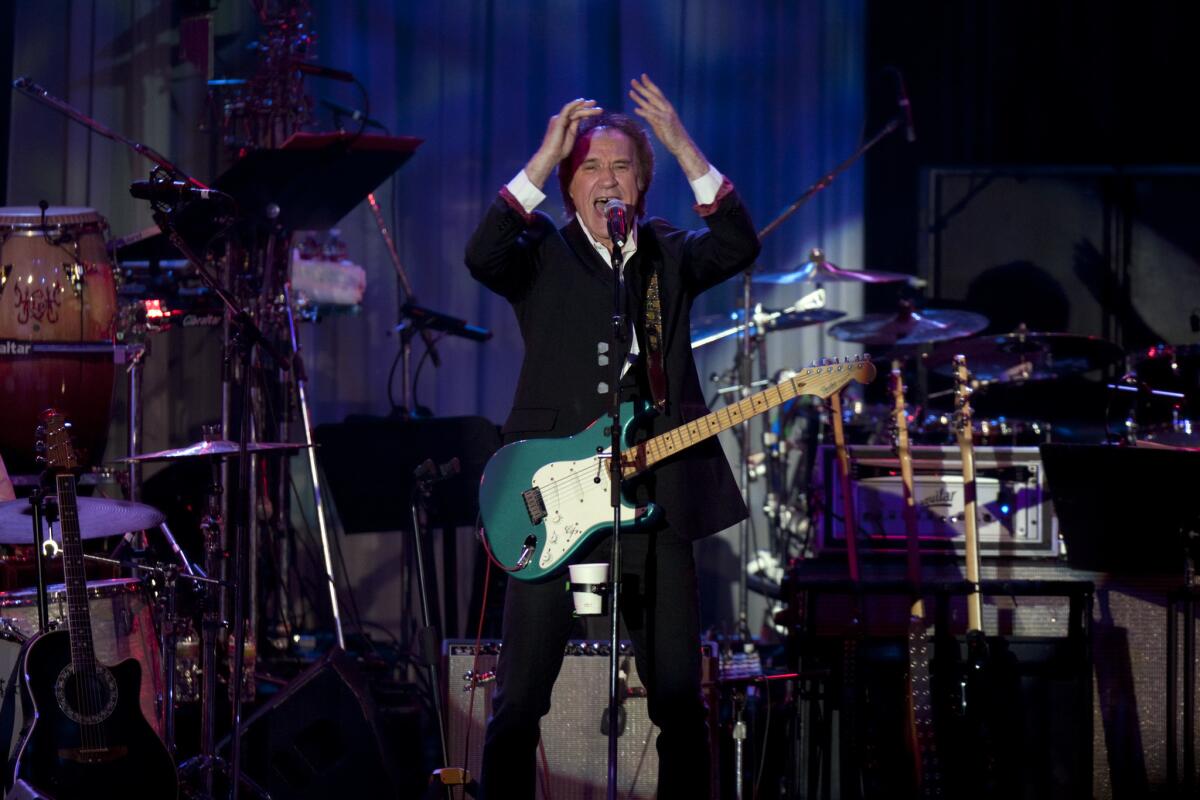

There never was anything somber about the Kinks’ concerts, the purpose of which was to create a sense of camaraderie between band and audience. Onstage, Davies’ energetic calisthenics and campy, beery antics aimed to convey a taste of the warm sing-along togetherness that was his and Dave’s childhood introduction to music-making in regular gatherings of their extended family.

Since turning 21, Davies has sung much less frequently about women than most heterosexual male rockers, for whom sex and relationships are the primary subject. When he does, the portraits have been invariably tender-hearted, even when women jilt him or, in “Lola,” turn out not to be women at all.

His down-to-earth focus has little, if any, room for spirituality; for Davies, psychic sustenance lies elsewhere. A few songs touch tangentially on religion — a silly, vaudeville-styled sermon about the game of cricket, or “God’s Children,” which protests organ transplantation as unnatural – Davies’ reaction to the theme of “Percy,” an obscure early-Seventies film about a penis transplant for which he provided the score. The only Davies song that really delves into matters of faith is “Big Sky,” from “Village Green.” In it, he sympathizes with a deity who’d like to relieve humanity’s sorrows but is too overwhelmed and preoccupied to act – a God who can’t manage to get out of bed and face his day.

I’ll rest my case for Davies as rock’s most humane, empathetic, poignant and idiosyncratic songwriter-performer with “Art Lover.” It’s a jaunty but heartbreaking song from the early 1980s in which the singer puts himself in the place of a pedophile for whom “jogging in the park is my excuse to look at all the little girls.” The man lurks and looks, but he’s a moral human being who’s steeled himself never to touch: “I’d take her home, but that can never be/She’s just a substitute for what’s been taken from me.”

Its germ was likely Davies’ sadness at being a divorced dad who missed his daughters, but the empathy and imagination that suffuse his artistry took it somewhere else entirely. If there is a comparable song I haven’t heard it, and certainly not from any of his fellow inductees in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

It should be said that Davies the artist is, unsurprisingly, more humane than Davies the person, especially where his younger brother is concerned. He once introduced a concert number showcasing Dave by announcing, “now we’ve reached the point in the show where we let the little twerp try to express himself as best he can.” I suppose they remained band-mates for a third of a century because Dave knew there were no better songs he could play, and Ray knew he could have no more flexible, willing and confidently rocking band than the Kinks.

There’s nothing more to demand from Davies as he pushes into his eighth decade, still performing live with the old vitality and warmth. For me, he completed the circle at age 63, when, after more than 20 years of failing to measure up to his old songwriting standards, he recaptured his powers with his second solo album, “Working Man’s Cafe.”

I’ll give him the last word, from that album’s “Imaginary Man,” in which he looked at himself and tried to sum things up.

“I was always in your head, to raise your expectations. ... Involved you in all my crazy schemes / And took you to places you’d never been.”

Well said, Ray, and happy birthday to you.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.