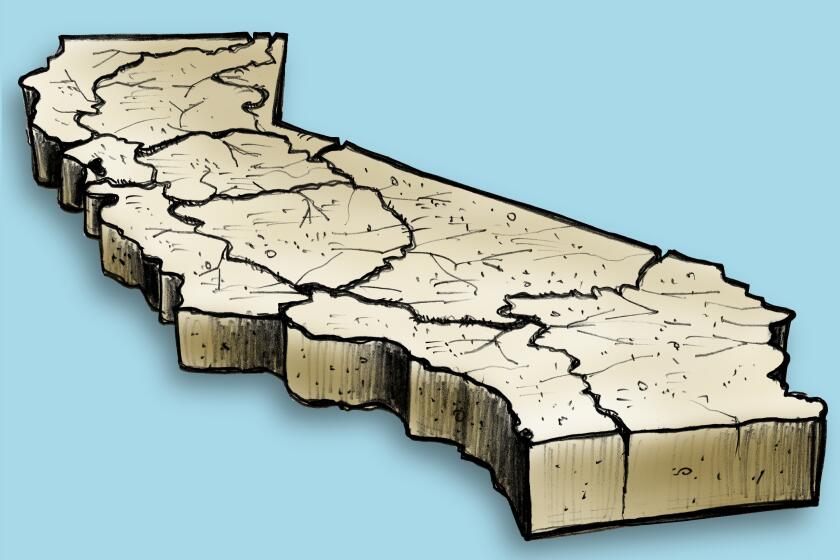

California snowpack is far above average amid January storms, but a lot more is needed

- Share via

A series of atmospheric river storms has brought California heavy rains and above-average snowpack across the Sierra Nevada, but experts say the state still needs many more storms to begin to emerge from drought.

The Sierra Nevada snowpack measures 174% of average for this time of year, but there are still three months left in the snow season, and the snow that has fallen to date remains just 64% of the April 1 average.

“It’s definitely a very exciting start to the year and a very promising start to the year. But we just need the storm train to keep coming through,” said Andrew Schwartz, lead scientist at UC Berkeley’s Central Sierra Snow Laboratory.

Storms swept in from the Pacific last week, bringing torrential rains and triggering major flooding in the Central Valley and other areas.

“The significant Sierra snowpack is good news, but unfortunately these same storms are bringing flooding to parts of California,” said Karla Nemeth, director of the state Department of Water Resources. “This is a prime example of the threat of extreme flooding during a prolonged drought as California experiences more swings between wet and dry periods brought on by our changing climate.”

President Biden will be visiting California this week following the winter storm that left the state with closed roads, freezing temperatures and a Venture County city evacuated.

The next storm is set to arrive Wednesday and continue Thursday, bringing more flooding and snow in the mountains.

“While we see a terrific snowpack, and that in and of itself is maybe an opportunity to breathe a sigh of relief, we are by no means out of the woods when it comes to drought,” said Nemeth, who urged Californians to continue to conserve water.

State water officials held their first manual snow survey of the year Tuesday at the Phillips Station snow course, one of more than 260 sites across the Sierra Nevada where the state tracks the snowpack.

“No single storm event will end the drought. We’ll need consecutive storms, month after month after month of above-average rain, snow and runoff to help really refill our reservoirs so that we can really start digging ourselves out of extreme drought,” said Sean de Guzman, manager of snow surveys for the Department of Water Resources.

California’s largest reservoirs remain very low after the state’s driest three years on record. Shasta Lake is at 34% of capacity, while Lake Oroville is 38% full.

Yet the start of this wet season has brought California some much-needed relief. State officials said the snowpack for this time of year is the third largest in the last 40 years, ranking behind 1983 and 2011.

If the rest of the wet season turns out to be very wet, experts say there is a chance that California’s reservoirs could refill in the summer.

“It could be a drought-buster of a year if things continue on a wet track,” said Dan McEvoy, regional climatologist at Western Regional Climate Center in Reno.

Excessive groundwater pumping has long been depleting aquifers in California’s Central Valley. Now, scientists say the depletion is accelerating.

But he and other scientists say that recovering water supplies to a manageable level in the Colorado River’s badly depleted reservoirs would take much longer, and that reversing the long-term declines in groundwater in California would also take many years, if aquifers are allowed to recover.

Southern California relies heavily on imported water from Northern California and the Colorado River. Recent storms have boosted the snowpack in the Rocky Mountains, bringing a modest increase to the Colorado River. The snowpack in the Upper Colorado River Basin now stands at 142% of the median over the last three decades.

That snow can only go so far, however, in helping reservoirs that have been drained by years of overuse and a 23-year megadrought amplified by climate change. The Colorado River’s largest reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, can hold years of runoff from snowmelt, but their levels have dropped to about three-fourths empty.

“Lake Mead is not going to fill up if we have a 200% of normal precipitation year,” McEvoy said. “It would take a string of those years to really make a dent in the water levels of those massive reservoirs in the Colorado system.”

After three extremely dry years in California, the wet start to winter might signal a shift to wetter conditions. But water officials cautioned that a year ago, December 2021 brought heavy snow, and then the storms stopped and the state saw a record-dry January through March.

“We’re cautiously optimistic at this point. But we all know what could happen if the pattern turns dry,” De Guzman said. “This year’s snowpack is actually better than where we were last year. But at this point, we have over half of an average year’s snowpack, and with roughly three more months to build upon it. It’s still early in the season.”

The biggest of last week’s storms, on Friday and Saturday, was a large and warm atmospheric river, called a Pineapple Express, which dumped rain and snow across the mountains.

Nearly 6 feet of snow had piled up as of Tuesday at the snow laboratory at Donner Pass. But because the latest storm was warm, Schwartz said it brought more rain than snow. The next storm is expected to be colder and bring 2 to 3 feet more snow at the lab Wednesday and Thursday.

“Realistically, we’re looking at needing several above-average years to come out of the drought,” Schwartz said.

“We’re so far into drought that we’re really going to need those multiple years to help pull us out at this point,” he said. “We still need to keep up with our water restrictions and just keep our fingers crossed that the storm cycle continues.”

Southern California will continue to see heavy rainfall through the rest of the week, and likely into next, forecasters say.

Water management officials said the abrupt shift from dry to wet over the last month shows both the dramatic fluctuations that happen naturally in California and the need for the state to adapt to more such extremes with climate change.

“Climate change is bringing never-before-seen extremes — from record dry periods with temperatures reaching new heights, to intense storms that produce rivers of water in short periods of time. We must learn how to manage through these extremes,” said Deven Upadhyay, executive officer and assistant general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

He said that requires investments in water storage, conveyance infrastructure and the development of more local water supplies.

The storms that have been rolling in fit with patterns that California has seen historically, said State Climatologist Michael Anderson.

“It’s just a good winter storm. The thing is, we’ve been missing them the past three years,” Anderson said.

Schwartz said pinpointing the effects of climate change on the latest storms would require attribution studies.

“But the changes that we see with climate change definitely make it more likely to see these types of wild events that we’ve had over the last couple of weeks,” Schwartz said.

The latest maps and charts on the California drought, including water usage, conservation and reservoir levels.

As for how long it might take for California to emerge from drought, that depends on recovering from water deficits that have accumulated over the dry years, said Jeanine Jones, drought manager for the Department of Water Resources. She said that would include regaining soil moisture, refilling reservoirs and also recovering from years of declines in groundwater levels.

In one recent study, scientists found that the pace of groundwater depletion in California’s Central Valley has accelerated dramatically during the drought as heavy agricultural pumping has drawn down aquifer levels to new lows. More than 1,400 dry household wells were reported to the state last year, many in farming areas in the Central Valley.

Jones pointed out that groundwater levels in many areas are now much lower than they were 10 years ago.

“We had dramatically reduced groundwater levels throughout much of the state,” Jones said. “And that’s really key because especially for drinking water, because … the majority of water systems, especially smaller ones, are really highly reliant on groundwater as a source.”

Even if the whole year turns out to be wet, she said, “that will not recover our storage fully.”