- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — John Heenan knows the terror of feeling a sting on his foot, then looking down and seeing two bright red puncture wounds about an inch apart and a massive rattlesnake slithering away into tall grass.

It was a summer morning in 2017, and the 74-year-old horticulturist was carrying a box of fruit in a Marin County orchard when, he said, “I stepped right on him, then called out to a partner, ‘Hey, I’ve been bitten by a rattlesnake.’”

It’s a snapshot imprinted in Heenan’s brain. “The fangs struck a vein, and I could feel the venom moving throughout my system,” he recalled, wincing at the memory. “I started seizing up, and struggled to breathe as though I had the wind knocked out of me.”

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

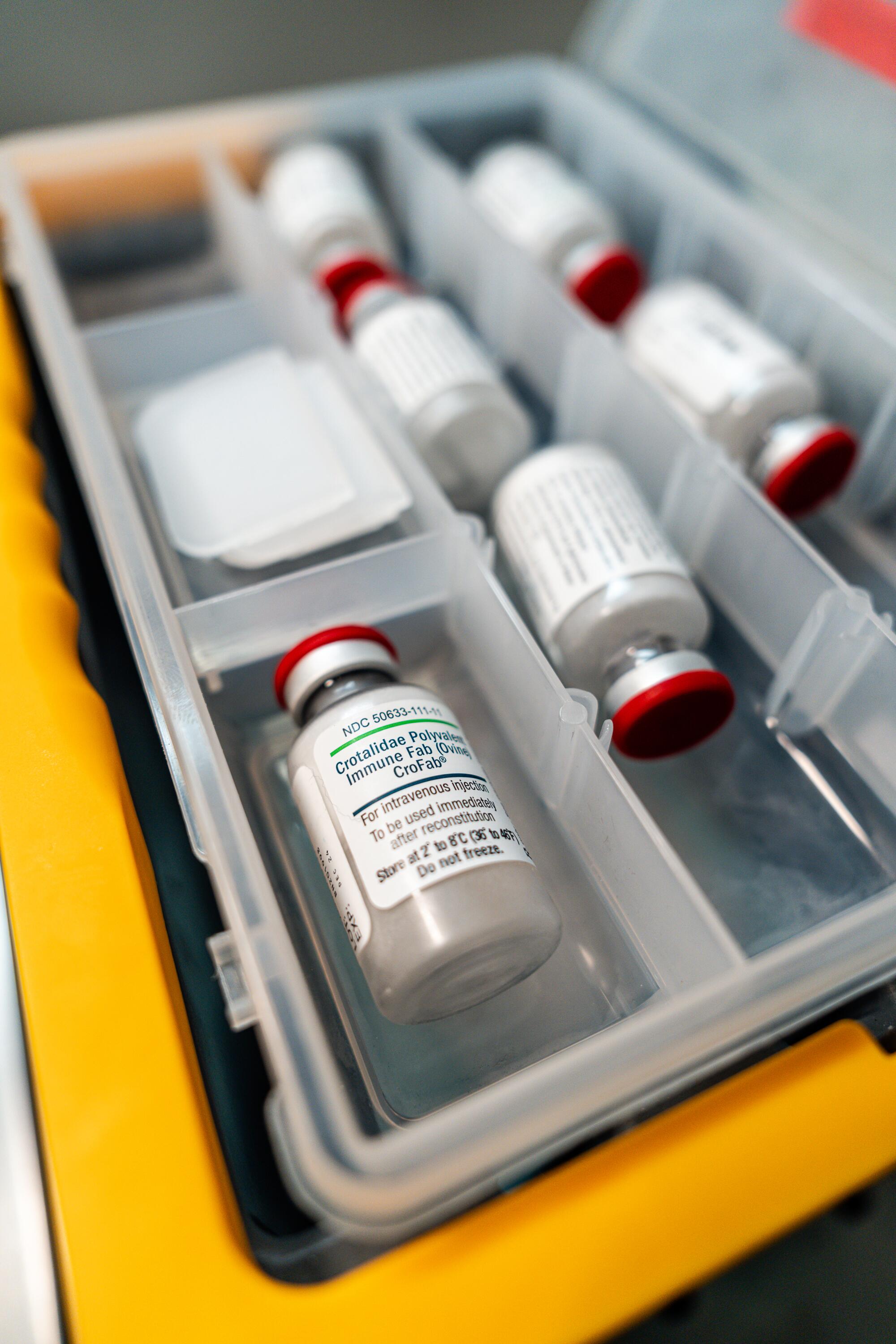

Heenan was rushed to a hospital, where he spent the next four days in a coma. During that time, he was administered 28 vials of antivenom intravenously at a cost of $3,400 per vial.

When he regained consciousness, there were two people at his bedside, his wife and expedition doctor Matthew Lewin, who smiled and said, “You are one lucky guy.”

Heenan would later learn that Lewin was hot on the trail of a novel treatment for the long, agonizing and often deadly effects of venomous snakebites: It’s a pill that he says “is intended to at least buy victims enough time to get to the hospital.”

Plans to build a $200-million water pipeline across the Mojave Desert to supply the city of Ridgecrest are angering environmentalists, farmers and miners.

Snake venom is a complex cocktail of toxins, amino acids and proteins that evolved primarily to immobilize and kill prey, but it also prepares tissues for digestion. In humans, venom causes severe swelling and instability of blood pressure, neuromuscular weakness and paralysis, hemorrhaging, and the death of skeletal muscle, leading to permanent tissue loss and amputations.

The World Health Organization estimates that 138,000 people are killed by venomous snakes annually, and most of them die before they can reach emergency medical care. This suffering goes on with little outrage or publicity because snakebites most often occur in impoverished, backwater areas, and there is no easy way to treat snakebite in the field.

Nature has provided an abundance of slithering assailants to watch out for: rattlesnakes, copperheads, water moccasins and coral snakes in the United States; kraits in Southeast Asia; taipans in Australia; Nikolsky’s vipers in Ukraine; Gaboon vipers with 2-inch-long fangs in Africa; and bushmasters in Central America. Then there are Russel’s vipers, big, irritable snakes responsible for 25,000 fatalities in India annually.

Typical standard-of-care antivenoms are extremely expensive, require refrigeration and must be administered intravenously in a hospital setting. They are also species-specific, meaning selecting proper antivenom requires knowing which type of snake bit you.

As a result, survivors of rattlesnake bites in Southern California, for instance, get a second painful surprise when presented with hospital bills totaling hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Lewin has been working for a decade to develop an easy-to-use, needle-free solution to all those problems with a drug called Varespladib.

What makes Varespladib promising is that it blocks phospholipase-A2, a highly toxic protein that is present in 95% of all snake venoms and plays a direct role in life-threatening tissue destruction, catastrophic bleeding, paralysis and respiratory failure. Proponents say the small synthetic molecule has the potential to stop or reverse neurological damage, as well as restore normal blood-clotting ability when administered immediately after envenoming.

Drug trials are being conducted by Ophirex Inc. — a public benefit corporation that Lewin founded with musician and entrepreneur Jerry Harrison in Corte Madera, Calif.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration a year ago granted Varespladib a “fast track” designation to expedite development and review of its safety and effectiveness, as well as Ophirex’s proposals for manufacturing and distributing the drug.

The Department of Defense has also invested about $24 million into the effort, saying the drug could provide an important capability to teams of special forces deployed in austere conditions where snakebites are a significant threat to life and limb.

“Ophirex may help us widen the window of time needed for evacuation in the event of a snakebite,” said Lindsey Garver, deputy manager for the Army Medical Materiel Agency’s Warfighter Protection and Acute Care Project. “There is also a psychological benefit to having something in your pocket that is life-saving.”

But getting any new drug from the laboratory to the market is an expensive, intricate process that can sometimes take just months to show promise but years to perfect.

The company is completing a Phase II clinical trial in the United States and India to determine the tolerability and potential side effects of multi-dose regimens of the drug in about 100 suspected or confirmed snakebite victims. Among them is a man who a month ago was bitten by a sidewinder rattlesnake near the desert resort city of Palm Springs.

A federal analysis of the results is expected sometime next year and will ultimately determine whether Ophirex has a blockbuster snakebite drug treatment with military and global market opportunities.

“I certainly underestimated the astonishing complexity of an undertaking such as this one,” said Lewin, 55, expedition physician for the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. “It’s humbling.”

The company has assembled an impressive board of directors: Derrick Rossi, a stem cell scientist and co-founder of Moderna; Curt LaBelle, chair of Global Health Funds; Tim Garnett, former chief medical officer for Eli Lilly and Co.; and Hans Bishop, co-founder of Altos Labs Inc., a biotechnology research company.

“Our company is trying to produce a drug for a neglected global crisis,” Rossi said. “The vast majority of people who are being killed or maimed by snake bites are village farmers and children working out in the fields without shoes.”

Varespladib was originally discovered and developed by Eli Lilly and Co. to suppress inflammation. The company abandoned that effort, however, after clinical studies failed to produce the desired results.

Since then, patents on the drug’s molecule have expired, providing Ophirex with “an opportunity for us to establish an appropriate patent portfolio,” said Nancy Koch, chief executive of Ophirex.

The proposed pill’s price tag remains unclear. “We haven’t made any estimates of pricing yet,” Koch said. “But we want to make the drug accessible around the world, and to make that possible we are studying ways to reduce manufacturing costs.”

To hear Lewin tell it, Ophirex emerged from a tragic event. In 2001, Joseph Slowinski, a herpetologist at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, died 30 hours after he was bitten by a small venomous snake in the mountainous jungles of northern Myanmar.

No antivenom was available at the remote site, a five-day hike from the nearest town. Heroic efforts to save him were unsuccessful.

A decade later, after a trip to the same region, Lewin, director of the academy’s Center for Exploration and Travel Health, began to ponder the possibility of a needle-free treatment that could be administered in the field immediately after being bitten.

Lewin initially set his sights on proving that the potentially fatal paralytic effects of certain toxic substances could be reversed with an antiparalytic drug administered via a nasal spray.

With that goal in mind, Lewin self-volunteered to become a test subject.

In a 2013 experiment conducted with a team of anesthesiologists in a research laboratory at UC San Francisco, Lewin allowed himself to be paralyzed with derivative of curare, a chemical typically administered intravenously as a paralyzing agent for surgical procedures.

Moments later, he said, “I couldn’t talk, felt dizzy and had trouble breathing.”

The team then administered the nasal spray, and within 20 minutes Lewin had recovered. The results of the experiment were published online in the medical journal Clinical Case Reports.

“It was terrifying, and I’d never do that again,” Lewin said. “But the experiment proved that paralysis could be reversed without intravenous medication.”

Wild animal rehabilitation organizations claim California officials are hassling their operations after decades of cooperation. The state denies it.

The arc of Lewin’s career has led him from emergency rooms to wilderness medicine as a doctor on scientific expeditions sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History, the Kellogg Foundation and National Geographic.

Not all of his research occurs in remote corners of the world, however. Studying the factors that influence snakebite severity means working with scientists such as William Hayes, a professor at Loma Linda University School of Medicine in Loma Linda, Calif., who keeps an assortment of snake venom available for testing in a laboratory refrigerator.

It also means studying the physical and financial struggles of survivors like John Heenan, whose hospital bills soared to more than $350,000 after he was bitten at the Indian Valley Campus of the College of Marin.

“Medicare eventually covered my medical costs, but I had to pay about 300 bucks for the ambulance service,” Heenan said, shaking his head.

The college, for its part, later planted a large digital welcome sign at its entrance that states: “CAUTION: Entering Rattlesnake Country. Be alert when walking.”

Heenan wouldn’t argue with any of that. But he also has high hopes for Lewin’s vision.

“Everybody should carry a few of those pills in their first aid kits and lunch boxes,” he said. “Of course, they should also watch where they step.”