Farmers Markets: A CSA model for seafood in Santa Monica

- Share via

Fishermen selling their own catch at Southern California farmers markets are vanishing. An attractive alternative is Community Seafood, a “community-supported fishery” that started selling last Sunday at the Santa Monica Main Street farmers market. Founded by two marine scientists, Sarah Rathbone and Kim Selkoe, it seeks to support local fisheries and provide ultra-fresh, sustainably caught fish to subscribers.

Rathbone, the owner, is the fiancée of Charlie Graham, who formerly sold crabs and spiny lobsters at the Santa Monica market. She and Selkoe started Community Seafood last June in Santa Barbara, using low overhead and direct sales to pay fair trade prices to local fishermen and delivering at three nearby locations. If the Santa Monica venture catches on, they hope to expand around Los Angeles in the next year, says Rathbone.

Subscribers pay in advance, on the CSA model, for a 12-week season, either weekly or every other week, for half a pound to 4 pounds; a few days before the market drop-off, they are informed by email what the catch will be, who caught it and how. If the weather is too rough for safe fishing, the delivery is postponed until a later week.

The selection usually changes weekly and recently included halibut, black cod, yellowtail and ridgeback shrimp, all wild and never frozen. Community Seafood also offers mussels and oysters from Santa Barbara Mariculture, which practices innovative methods of open-ocean aquaculture in the Santa Barbara Channel.

Prices are premium, from $18 to $32 a pound, but a sample of the king salmon from Morro Bay offered last Sunday ranked with the freshest and most delicious that I’ve ever tasted.

The community-supported fishery concept, in which members pre-pay for a “season” of fresh, locally caught seafood, is modeled on community-supported agriculture, which has become increasingly popular in recent decades. The fishery version started about five years ago on the East Coast with Cape Ann Fresh Catch in Massachusetts and Walking Fish in North Carolina, says Selkoe. About 30 such groups now operate around the country, but Community Seafood is the only one in Southern California, according to LocalCatch.org.

Transparency and the reduction of the number of hands that fish passes through from the ocean to the fork are two of the most appealing aspects of Community Seafood’s approach. A recent study by Oceana, a nonprofit conservation group, showed the nationwide prevalence of seafood fraud, including misrepresentation of its identity, where it is caught and whether it is wild or farmed. Such mislabeling has also taken place at farmers markets. Rathbone and Selkoe know their seafood and are devoted to preserving local fish and fisheries, crucial assets for subscribers who want fresh, environmentally sound, delicious fish.

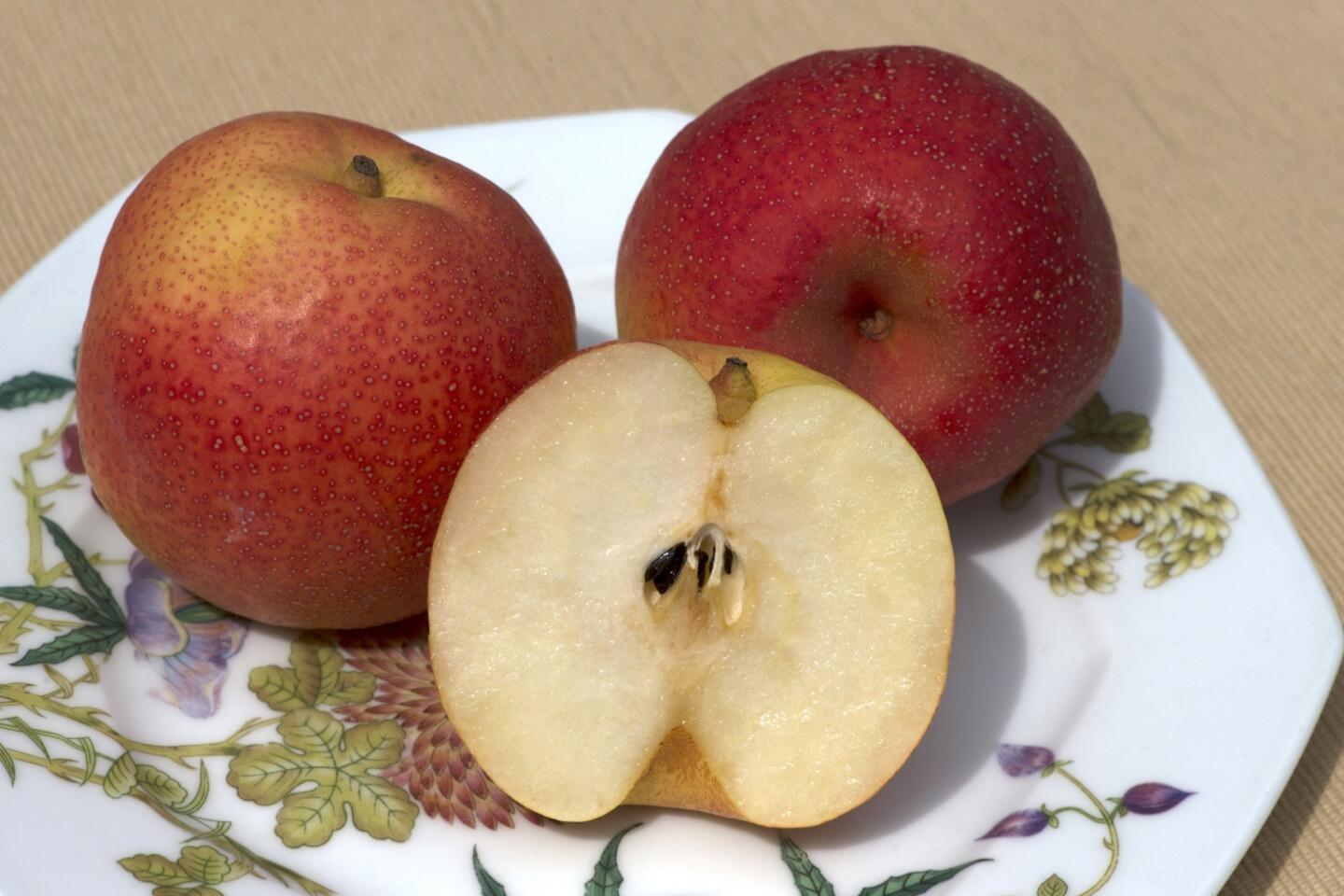

Enter the Papple

A novel variety with the crunch, juiciness and sweetness of an Asian pear and the red-blushed skin and round shape of an apple will make its domestic debut this weekend at Gelson’s markets under the improbable name Papple. It’s not actually a pear-apple cross — such hybrids never have borne fruit successfully — but a natural cross of Asian pears, artfully bred and grown in New Zealand.

Allan White, a virtuoso scientist for a company now called Plant & Food Research, bred the variety, technically named PremP109, in 1996, he says. It derives its gorgeous red-orange skin color, very rare in Asian pears, as well as long storability, from Huobali, a coarse-fleshed Chinese variety from Yunnan, and juicy, finer texture from Kosui, a standard Japanese-type Asian pear. Growers in Motueka, New Zealand planted about 12 acres and first exported the fruit last year, with great fanfare, to England, where the fancy retailer Marks & Spencer bestowed the name Papple.

Just two pallets, about 3,700 pounds of Papples, arrived at the Port of Los Angeles last Tuesday, so the fruit will probably just be around for a few days at Gelson’s, which has the exclusive marketing rights this season in Southern California. Priced at $6.99 per pound, they’re not for everyone, but preview samples were superb, looking and tasting like no other fruit.

“It has a slight tannic bite, balanced with floral acidity and sweetness,” said D.J. Olsen, formerly the chef at Lou Wine Bar. “It’s super-juicy, with excellent crunchy texture.”

“It’s like an Asian pear with flavor,” said Judy Babis, sous-chef of Gjelina.

White and his successor, Richard Volz, have also developed crosses with the rich flavor of European pears like Bartlett and the firmness and crunch of Asian pears, which are likely to revolutionize the pear industry when they are marketed in a few years. Properly ripened European pears have exquisite aromatic flavor and buttery texture but are tricky to bring to that ideal stage; all too often pears are eaten when they are either rock hard and tasteless or “sleepy,” as the English term overripe, mushy pears. Retailers tired of throwing out bruised pears have longed for the day when they could sell European-type pears ready to eat.

There’s no getting around it, traditional pears are just not convenient. Asian pears are much easier to handle but generally lack the intense, complex flavors for which European pears are prized. Hybrids of the two types, such as Kieffer and Le Conte, have been around since the 19th century but have been valued more for their supposed fire blight resistance than for flavor.

It has taken three generations of crosses over several decades for the New Zealand breeders to come up with promising new varieties with just the right mix of fruit qualities — Bartlett flavor and Asian pear crunch — along with the productivity, long storage and shelf life, and attractive appearance necessary for commercialization. I was lucky to taste first-generation samples eight years ago and can’t wait until third-generation European-Asian crosses are available.

The Papple, here now, isn’t a game-changer of that magnitude, and the name is a bit hokey, but it is well worth exploring by the fruit-curious.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.