An ace L.A. team is the secret sauce behind the Red Boat cookbook

- Share via

Cuong Pham, the founder of Red Boat Fish Sauce, has the kind of business story that should be adapted for a Netflix series. He arrived in the United States from Vietnam in 1979, and the cultural adjustments included never quite being able to duplicate the taste of his mother’s cooking — which proved true even when his mother immigrated to the U.S. in 1990.

The missing element? Superior-quality fish sauce, a cornerstone seasoning in Vietnamese cooking. The stuff his family could find in Bay Area markets tasted salty and one-dimensional; it was nothing like the complex umami infusion that the ingredient imbued when the family lived in Saigon.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In 1984 Pham worked as a systems engineer for Steve Jobs when Apple was a small company; their paths didn’t cross for long, but Pham never forgot Jobs’ utter sense of devotion and belief in a product. Later, during the first tech boom, Pham was a consultant traveling frequently to Southeast Asia, and when he was in Vietnam he would think about the fish sauce conundrum, even touring factories on Phú Quoc, an island considered to be the epicenter of traditional fish sauce production. Eventually he invested in a small fish sauce company, and when it went belly-up he decided to learn the craft and run the business himself.

After months of trial and error he felt his team had mastered the formula for nuoc mam nhi, a first pressing of fish sauce made only with black anchovies and salt, fermented and aged in barrels. His mother gave the product her blessing. He sold the fish sauce at first to small markets across California, rebranded after a discouraging first year and then, when the New York Times mentioned Red Boat in 2014, hit the jackpot. It soon gained status as a cult product that helped change the way Americans understood and used the ingredient.

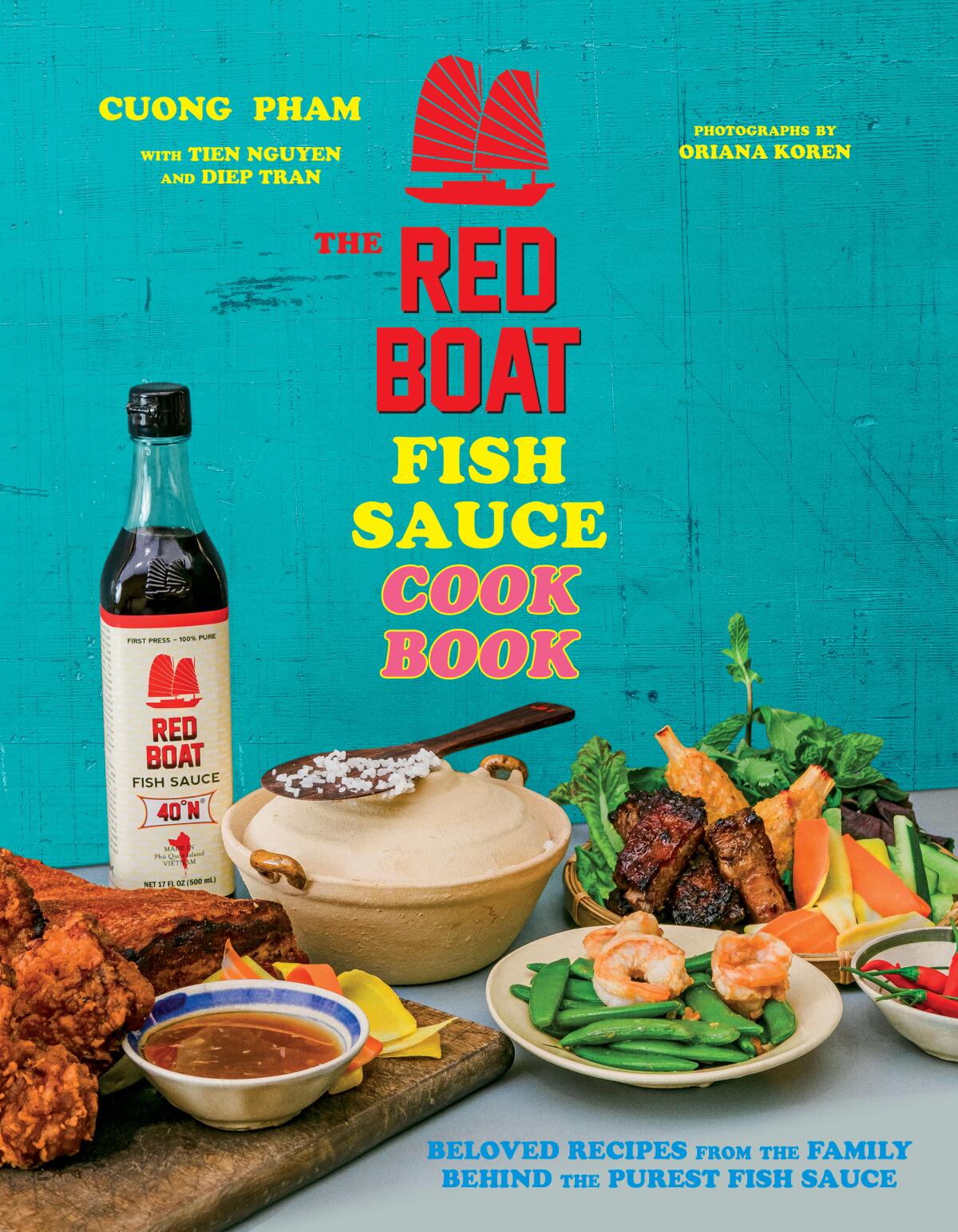

Given the success story, it’s no surprise that Pham’s first book, “The Red Boat Fish Sauce Cookbook,” has such a straight-ahead title. It includes the expected introduction on the company’s origins and an inviting survey of family recipes. Recipes showcase not only how nuoc mam nhi richly and traditionally interacts with garlic, black pepper and lemongrass that sauce the pork chops and broken rice for com tam but also show off the sneaky depths it brings to marinara.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

This book about a secret ingredient has its own secret weapons: It came together via the talents of an ace Los Angeles team. Oriana Koren’s gorgeous photographs capture Saigon street scenes and glimpses of daily Vietnamese life with a respectful eye. Writer Tien Nguyen and chef Diep Tran, who ran Good Girl Dinette in Highland Park for nine years and is now Red Boat’s recipe and development chef, give the book its page-turning narrative flow; flip right to page 173 for the essay on the importance of salt, and then to the back for the charts on perfecting dipping sauces and Pham’s itinerary for a nostalgic eating tour through Saigon.

Nguyen and Tran are partners. They were in Vietnam finishing research for the book in March 2020 when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. In a conversation edited for length and clarity, we talk about what it was like as a couple to hunker down and work together in isolation after they arrived home, and the broader meanings woven into a book that uses one ingredient as its nexus.

Have a question?

So you arrived home from a research trip in Vietnam in March 2020, you went into quarantine and … you wrote a cookbook together in the middle of those dark months. What was that process like?

DT: In the beginning, when we started dating, we were like, “Well, we would never work together. That’s just not going to happen.” And yeah, we made an exception, and [addresses Nguyen] it turned out well, babe!

It worked out because we had our clear delineations. Of course we’d help inform the other person’s work and talk about how to stay with the book’s narrative. I would take care of the recipes and give some context, and then Tien had final say over the words. We didn’t really clash. I think we both knew what we wanted to do, and it didn’t overlap too much.

TN: Yeah, I think philosophically we were aligned. We did have some arguments about things like ingredients, because I’m a bad shopper, I guess?

DT: We needed a lot of groceries for recipe testing and we were trying not to go out too often. So it was high stakes!

I so get it. Do you think your relationship is different in any way after writing this book together?

DT: It’s nice to know that we could work together. When Tien has co-written cookbooks before, I didn’t know her process. With this book I would write an initial recipe and include a little context, and then from there Tien would finagle it and write the headnote. And I was like, wow, you took all that jumble and distilled my convoluted overthinking to tell readers to just, you know, cut the onions. I’ve always thought Tien is lovely but now maybe I appreciate her even more.

TN: Aww.

I wanted to ask you both about your respective relationships to this particular work. Tien, how is this experience different from the other two cookbooks that you’ve worked on?

TN: The cookbooks I wrote with Roy Choi and Adam Fleischman touched on Vietnamese ingredients, and Roy’s had a couple of Vietnamese dishes too, but this was the first book I’ve written explicitly about Vietnamese food culture. And it’s not just about Vietnamese food, though it’s a big part of it, but it’s also about the Vietnamese American experience. The familiarity I have with the subject is on another level than the other books I’ve done. And I knew the product and liked it, so that helps. And yeah, I mean, obviously working with Diep was … different. [They both laugh.]

I’ve had good experiences working with people I co-wrote books with, but I do know sometimes it can be difficult to ask a chef, “What do you mean by this instruction?” or “Can we double-check this ingredient?” With Diep it was like, “Hey, it’s 2 o’clock in the morning, and I really need to ask you this question right now.”

We originally wanted to go up to Northern California and do a lot more cooking with the Pham family, to taste their dishes and the recipes in person and get a sense of the beat and tone of their cooking styles. Obviously we couldn’t do that because of the pandemic. So Diep was developing all the recipes here, and to be able to taste so many iterations of the same recipes really helped inform the way I wrote the recipes.

DT: I made you eat a lot of pork.

TN: I ate so much pork belly.

And Diep, you were familiar with the brand soon after it came on the market in the early 2010s. I remember you name-checked it with your “Red Boat bacon and eggs” dish on the brunch menu at Good Girl Dinette. Broadly speaking, before Red Boat, were you frustrated with the quality of fish sauce you could find in America, and did that inform how you approached cooking Vietnamese flavors here?

I wasn’t frustrated with the quality of fish sauce here before I tried Red Boat, but I grew up with my grandparents and heard their kvetching about it. I left Vietnam when I was 5, and I remember certain things but nothing about fish sauce. But for people in my parents’ and grandparents’ generation, they had to hustle because the war changed everything. One day you could have a steady job and the next day you don’t. My grandpa had a bunch of different careers, one of which involved distribution of fish sauce. So in America they would talk about how the fish sauce wasn’t first press even if the label said otherwise, either because the ingredient list revealed the lie or mostly because it just didn’t taste like first-press fish sauce. They had a favorite brand when I was growing up here because it was the only one available, but it was a very — how does that song go? — “If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with” kind of thing.

I thought first-press fish sauce was a unicorn — that it wasn’t like it was extinct but like it didn’t even exist. When I tasted Red Boat for the first time, it finally made so much sense why my grandparents had kept talking about it. But here’s why I really got so excited: Not only was the product amazing but here was a Vietnamese American giving the artisanal treatment to something that largely before had been considered a commodity product. There was previously no transparency in the production of fish sauce, no sense of where it came from or who was making it.

I felt like Red Boat’s entry into the market would inspire a generation of Vietnamese Americans — and Asian Americans — to think about the culinary legacies that they have. You know, soy sauce shouldn’t be an anonymous product either. But the taste of Red Boat was so excellent that I changed the recipes in my restaurant immediately. Which is insane, because here I am changing a 20-gallon recipe for pho, but I was so committed it wasn’t even a question. It was like, I’ve got to stay up late and do this.

We used the fish sauce in our recipes, we sold bottles of it in our merch section, and someone was like, “Are you sponsored by Red Boat now?” I’m like, no, I’m just evangelical about it. The transparency of the company was also important because international fisheries are notoriously rife with labor violations and human rights violations. It was great to know about a product that didn’t perpetuate that chain of behavior.

When you were both working on this book, what audience did you have in mind? Who did you most want to reach?

TN: I wanted to reach myself, honestly. I kind of approach all of my writing that way: I want to write things that I would want to read or have been wishing was in the world. This was a chance for me to really get into the nuances of Vietnamese cooking in quite a bit of detail. There’s an entire section about making dipping sauce …

I love that section! You include 7 Up as a sweetener option!

TN: When I was working on it I wanted it to be helpful to me because every single time I would make nuoc cham I ended up with a tub of it. I wanted a little ramekin but I could never get the ingredients in balance — I put in too much acid, I put in too much sugar — and I’m constantly trying to correct it and I just end up with this massive amount of dipping sauce. So the book is for someone like me who is familiar with Vietnamese cooking but wants more guidance.

DT: We keep trying to think of the feminine version of the word “avuncular” — I always forget it because it’s a mouthful — but I wanted to come from an avuncular place without over-explaining what the dish actually is. You know, if you didn’t know how to make com tam, we would teach you without being like, “Now let’s go to an ancient country and I’ll put on my conical hat …”

TN: Yeah, the soundtrack to this book does not include a gong.

DT: Right, nor a two-string guitar. We didn’t want to trap Vietnamese food into “essentials,” which is a word I kind of hate. Like, here’s a glimpse into a cuisine — which is what we wanted to achieve — rather than caging the cuisine in a terrarium where it doesn’t go anywhere. And we wanted to present the ingredient on its own terms. We don’t have a chapter about fish sauce called “Sorry It’s Stinky.”

TN: Really, we were thinking of an audience interested in fish sauce, period.

Even though this book focuses on an ingredient that comes from a very specific place, it also strikes me as a beautiful California story. Red Boat as a business sprang from entrepreneurialism by a man who learned from Steve Jobs. Much of the team behind the book has ties to Vietnamese immigrant communities in California, and some of the recipes (Sergio Peñuelas’ Nayarit-style fish, Bryant Ng’s charcuterie fried rice) evoke Los Angeles. Does that observation seem accurate?

DT: I think you’re correct. I mean, San Jose and Orange County have the two largest Little Saigon communities in the country, and there’s some rivalry there, but their ethos is part of the book. I mean, Little Saigon in Orange County was created because we thought we lost Saigon, right? But now, Little Saigon has become so much its own style that people from Saigon come to see. Borders are porous. We definitely didn’t want to give the idea that Vietnam doesn’t interact with anywhere else. Even in Vietnam, Vietnam interacts with Cambodia, interacts with Laos, interacts with the world in general.

TN: The birth of the Asian American political movement really started in California, and even if you don’t have much background being involved in the movement, it just permeates differently in California — the ways you think about Asian American foods, the way you think about Asian American cultures, and the ways they are represented in the media.

DP: It’s critical mass. There are enough of us and we can talk to each other and create something without accommodating the needs of others — a completely different experience than if, say, you’re the one Asian in an entire town. This is our food, defined by our own community, and then we can make something like this book and transmit it the general population on our own terms.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.