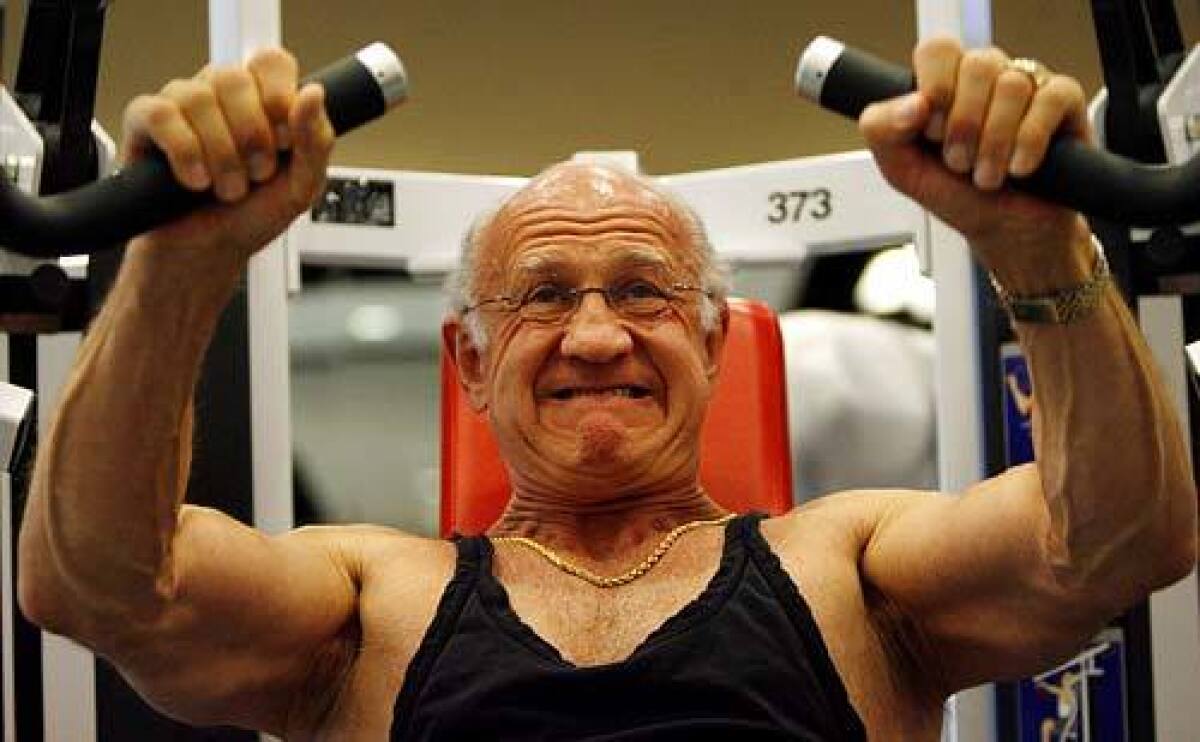

Dr. Jeffry Life believes he’s the picture of health

- Share via

“Oh, you mean the guy with the 70-year-old head and the 20-year-old body-builder body? That picture has got to be Photoshopped.”

Dr. Jeffry Life smiles when I tell him about the general reaction I get about the famous picture of him with his shirt off, the shot that turned a mild-mannered doctor in his mid-60s into a poster boy for super-fit aging and controversial hormone replacement

Appearing in medical-clinic ads in airline magazines and newspapers (including this one), the incongruous photo juxtaposes a bald, white-haired, septuagenarian head on top of a rippling, V-shaped torso worthy of an Olympic gymnast or powerlifter. Completing the effect of macho, forever-young vitality, Life’s left hand casually dangles by his thumb from a jeans front pocket, in a cool cowboy swagger.

“Yeah, I read on the Internet that people think it’s digitally enhanced,” says the soft-spoken Life (which really is his name, translated from the German by his immigrant great-grandfather) with a laugh. But the body is real -- built by a relentless, six-day-a-week exercise regimen that includes hard cardio, heavy weights pushed to the max, martial arts, Pilates, a strict low-glycemic carb diet and lots of supplements. It has also, for the last seven years, been hormonally enhanced by a program that includes testosterone and human growth hormone -- a therapy Life views as entirely appropriate, even necessary despite the medical evidence questioning both its effectiveness and safety.

Testosterone replacement can enlarge the prostate and raise levels of prostate-specific androgen, used in cancer-screening tests. Human growth hormone could increase the risk of diabetes and cancer, and the National Insitute on Aging recommends it not be used for anti-aging purposes. (See related story for details.) But both are mainstays of the not-quite-mainstream field known as anti-aging medicine.

Life’s enthusiasm is undimmed by such skepticism. “The fact is that every male over 50 or 55 suffers from a slow, insidious fall in testosterone levels,” he says. “You don’t notice it for a long time until your ‘T’ levels cross a certain threshold. Then you suddenly find that you lose your enthusiasm, your sex drive and can’t maintain muscle mass anymore -- even if you work out. It’s even worse if your HGH levels are falling off the table. That’s what happened to me.”

‘Years of sloth’

Like most people, Life didn’t give a thought to his testosterone level, his HGH or his fitness as he built his career as a family practice doctor in West Virginia and Pennsylvania. A lapsed Masters swimmer who became inactive in his mid 40s, the father of five became fat and borderline diabetic -- “a typical stressed-out middle-aged doctor who ate, drank and didn’t practice what he preached. It was years and years of sloth.”

That changed the day Life, then 60, picked up Muscle Media magazine and read about “the Challenge,” a 12-week, before-and-after fitness contest. His competitive fires lighted, Life sent in his before photo and hit the gym.

Three months later, he’d dropped 25 pounds, cut his body fat from 28% to 10%, got genuinely ripped and was named one of the contest’s 1999 “Body for Life” 10 grand champions.

Entering his 60s energized, Life was good. “I’d gone from fat, aging and tired to lean, strong, energized and highly motivated with an incredible zest for life,” he said. “If I could do this in my 60s, I truly believe anybody can.”

But by age 64, Life found himself shrinking.

His muscles didn’t respond to workouts like they did a few years before. Abdominal fat started piling up. He began feeling mildly depressed. And he wasn’t waking with an erection as often as he used to.

It was a condition he would soon know as andropause, the insidious creep of declining testosterone.

It was time for his second epiphany -- and the photo that would change everything.

A turning point

At a nutritional conference in Las Vegas in 2003, Life heard a presentation from Cenegenics, a local clinic making a name for itself in what proponents call “aging management” medicine. Its therapy included exercise, diet and treatment with testosterone and human growth hormone.

Testosterone, produced in the testicles, is key for maintaining bone density, red blood cell levels, muscle bulk, libido, even a sense of well-being. HGH, secreted by the pituitary gland as a childhood growth agent, does similar jobs, including enhancing skin tone and texture. Both have been used as illegal performance enhancers by athletes for decades -- and both decline steadily with age.

Adult HGH levels decline by half from age 20 to 60, and the loss accelerates thereafter. Adult testosterone levels begin a steady fall-off by age 30 or 40 that continues throughout life, although symptoms may not show up for decades, if at all.

Noting that such declines are part of the natural aging process, many doctors are openly skeptical of the wisdom of replacing these hormones.

“These programs are completey illogical,” says Dr. Robert Baratz, former president of the National Council Against Health Fraud and an assistant clinical professor at Boston University School of Medicine. “They defy what we know about science and biology. They prey upon people’s desires to wind back the clock, as if such a thing were possible. But there is no mechanism for doing that in nature.”

Life, however, was intrigued by the potential of such regimens. “I’d never thought about hormone levels before,” he says. He made an appointment at Cenegenics and had his blood tested.

His T level, he was told, was terrible -- 100 nanograms per deciliter (ng/dl) on a scale where normal is more like 200 to 1,000 ng/dl. “280 might be a passing grade on that scale,” he says, “but it’s a D-minus. And mine was even worse -- an F.” He scored another “F” in his HGH level, according to Cenegenics’ tests.

In June 2003, Life became a Cenegenics patient, ultimately taking daily shots of HGH along with once-a-week testosterone shots, a regimen he still maintains.

The package isn’t cheap -- about $1,500 a month, including $1,000 for the HGH. But, he says, it worked.

“I could feel the difference quickly. Clarity of thought, a new, sharper focus, increased sexual function, bigger muscles.” He was so impressed that he packed up, moved to Las Vegas and joined the company.

After six months of seeing clients, Life had an idea to keep them motivated: Show them his body.

“They needed to know that I walked the walk.”

That might have been the end of the story -- until a year later, when a writer from GQ magazine, in to do an anti-aging story, walked by Life’s office. His eyes bugged out at the sight of the glossy 8 by 11 of the buffed, bald, jeans-wearing guy hanging on the wall.

The shot ended up in his article in the January 2006 issue of GQ.

“It was huge -- we were inundated,” says Life. “My boss didn’t want to admit it at first, but we all knew why: the old head/young body.”

Last March, Life gave up his position as chief medical officer at the company to start his own anti-aging practice, which emphasizes diet, exercise and testosterone. “HGH is too controversial right now,” he says, alluding to criticism of the hormone’s potential health risks. “And most of the time, exercise, eating properly and getting your other hormones in a healthy range will correct an HGH deficiency in two months.”

Life is still affiliated with Cenegenics, which pays him for use of the picture. He also uses it in his own ads and a billboard along I-15.

The picture has changed everything for Life. “It gives me the opportunity to spend more time on my book, my website business, coaching and capitalizing on my brand,” he says, as excited as a new college graduate embarking on a life of endless possibilities. In fact, he is a student again.

Wearing his trademark black T-shirt and New Balance running shoes, he goes to the University of Nevada-Las Vegas twice a week to take sports nutrition and exercise physiology classes.

And, of course, he still works out like crazy. “After all, I’ve got to hold up my image,” he says.

At the gym

The famous photo you see in ads today was taken in December 2004 when Life was 66. How does his body look now?

To find out, I met him at the Las Vegas Athletic Club, where Life hits different body parts five days a week at 7 a.m., normally with a trainer.

Life looks buffed, ripped. His arms and legs are heavily vascular, with pipe-like veins bulging over fat-free sinew.

He hammers himself hard on the machines -- five sets of chest flies, incline presses, decline presses, dumbbell bench presses, dips, leg extensions and many other exercises -- all done in ascending weights to the point of “failure,” where you can go no more on the last rep.

It’s the same strategy Life uses for cardio, blasting his home stationary bike on four sets of four lung-heaving, high-intensity intervals.

“When you go to failure, you push the skeletal muscles into a zone that makes them stronger,” he says. “You also force your heart muscle to make special ‘stress proteins’ that protect it from heart disease.”

Life also does Pilates twice a week and taekwondo three times a week.

“It greatly enhances my flexibility, but mainly I do it just because I always wanted to.”

Going full-speed is a joy at any age but maybe even sweeter when it’s so counterintuitive. At a time when his peers are gearing down, Life acts like he’s just getting started.

“At 71, I feel better than I’ve ever been. I’m as strong or stronger than I’ve ever been, with even more muscle mass than five years ago.”

Maybe it’s time for a new photo.

Staff writer Shari Roan contributed to this report.

heal th@latimes.com