We’re far more afraid of failure than ghosts: Here’s how to stare it down

- Share via

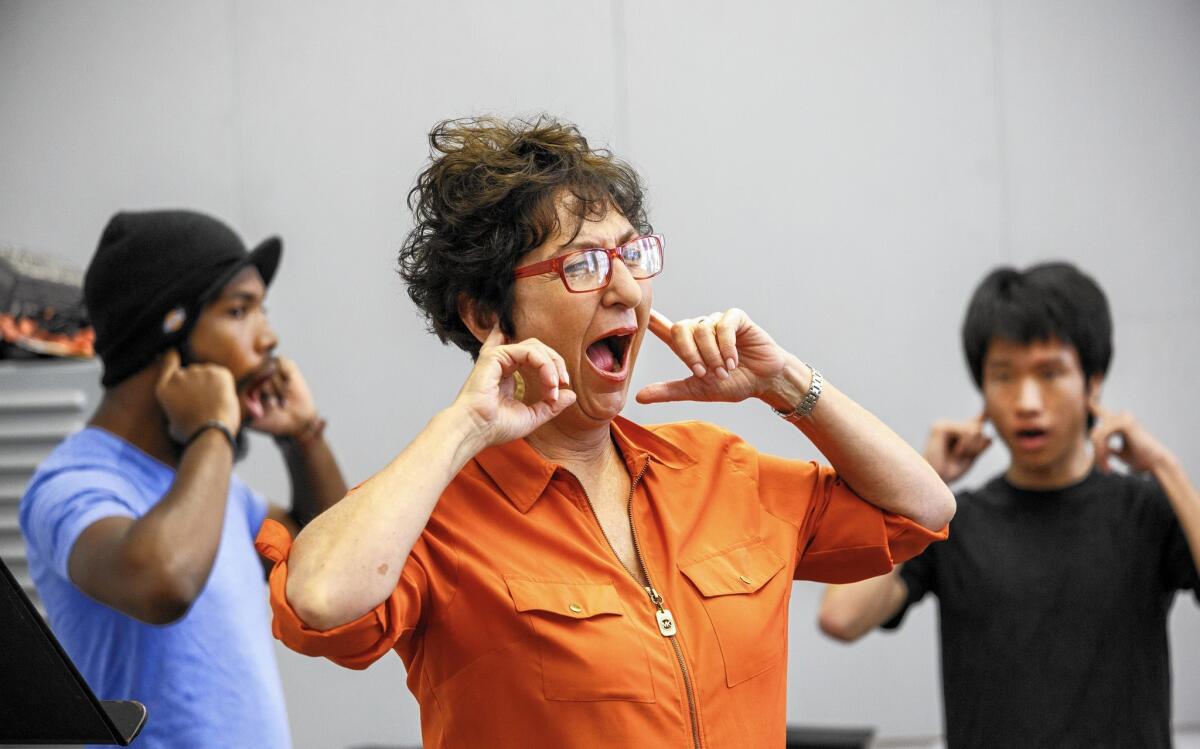

I sat at the edge of my seat, waiting to be called up. Hands freezing, heart racing, I tried to slow my breathing and calmly remember what to do. Breathe, got to breathe.

The instructor called my name. I walked to my spot, inhaled and expanded my rib cage. Nodded.

And began to sing “Shenandoah.” With an accompanist, in front of an audience: a class of 20 fellow voice students.

It was one of the most terrifying and exhilarating experiences of my life.

Fear and exhilaration do go hand in hand, and fear of failure is common. A recent survey by the social network Linkagoal found that fear of failure plagued 31% of 1,083 adult respondents — a larger percentage than those who feared spiders (30%), being home alone (9%) or even the paranormal (15%).

“Fear of failure is the No. 1 reason people don’t set goals or try new things,” said Mohsin Shafique, a former medical school student who is chief executive of Linkagoal, which was designed to help people set and achieve goals. One solution, Shafique believes, is connecting with people who share your ambition. “Sharing what you are doing with a community that not only gets it but also may have done what you are trying to do is very powerful. It’s why going to the gym when you’re trying to get fitter works better than doing it on your own.”

Los Angeles-based publicist Sharon House knows the euphoric lift many people get after doing something that frightens them. Always afraid of heights, House would never even go out on balconies. “It kept me from doing some things I really wanted to do, like going to the top of Machu Picchu.”

So, for Mother’s Day last year, House’s daughter Laurel helped her jump off a cliff. “She took me rappelling at Garden of the Gods in Colorado Springs,” House remembered. “They take you up a very slippery climb, put you in a helmet and harness, and then say, ‘OK, go.’ It was 5 feet to the edge; I walked to it on my tiptoes, then jumped backwards and free-fell about 6 feet. Pushed off and did it again. I did it all the way down, for about 10 minutes. There was no stopping me.”

Performance anxiety

Linda Hamilton, a former dancer in the New York City Ballet, now has a psychology practice working with performers and others dealing with fear — of performing, of dating, of changing jobs. She started her practice counseling dancers, initially through her column in Dance magazine, but then realized she could help many others too. “The people I work with are scared of failing and are passionate about what they’re doing. I try to teach them that you don’t achieve anything if you stay in your comfort zone,” Hamilton said.

“Fear of failure is fear of the unknown,” she said. “In some cases, we need fear. It’s what keeps us alive. But at the same time it can freeze you.”

Not everyone can do anything they want. “I do a thorough intake on a client, because sometimes they are not equipped for what they want to do,” Hamilton said. “They haven’t had the training, for instance, to start trying to be a professional ballet dancer at age 25. But we can find strategies for what to do instead.”

What often happens, according to Hamilton, is that people reframe their fears, and use a cognitive technique to see that the concerns are unfounded. “My client who was afraid of dating was also terrified of making friends, fearing that she would lose them if they moved or got pregnant. What she was really reacting to was feeling she had to be perfect for her mother, who kept all her feelings to herself. The girl took rejection very seriously and anticipated it even if it wasn’t real.”

The payoff

“The experience of going out of your comfort zone is not a pleasant one,” said Hamilton. “But the confidence, the feeling of relief — we call it ‘excitation transfer’ — are very intense. That sense of mastery, ‘Wow, look what I just did,’ is a learning experience. The fear itself is not pleasant, but people never remember it. What they remember is that positive high.”

That high, both immediate and long term, is due to a deluge of brain chemicals, most notably dopamine. “Our dopaminergic reward systems are geared for learning about our world and optimizing our odds for survival,” said neuroscientist Christopher Evans, director of the UCLA Brain Research Institute and an addiction expert. “So food, sex, drugs all promote dopaminergic signaling (at least initially, and then cues take over). Pain or noxious stimuli cause dopamine release, and so relief from any perceived danger or threat — in the case of your singing, the threat of being ostracized from a group — would explain that euphoria.”

When fear is crippling

Many performers experience a type of post-traumatic stress disorder in the form of stage fright. One incident may scar them for years. Barbra Streisand, famously and early in her career, forgot the words to “People” during a free concert in Central Park. She was so mortified, she stopped performing in public for almost three decades; she simply kept reliving that moment. Performers who have stage fright do not get that reward of euphoria. First there is terror, and then hyper-criticism.

Sara Solovitch, author of “Playing Scared: A History and Memoir of Stage Fright,” played classical piano from a very early age. When she was 11 or 12, she developed crippling stage fright, so severe that her fingers, dripping sweat, would slip off the keys. “I was a talented pianist, but what I was experiencing was not natural. Even though you know your life is not being threatened, that you aren’t skydiving or bungee jumping, what happens in your body and your brain is the same. It doesn’t matter: Your brain is being hijacked, and your rational mind isn’t there anymore.”

Solovitch gave up the piano and became a writer. But after 30 years she went back, “primarily because all my children played and my youngest wanted me to play with him. I took lessons in jazz piano, thinking that he would soon forget about it, and it would all pass. Instead, it triggered something and I started playing all the time, practicing two to three hours a day.”

Her fear of performing in public, however, “had been preserved in formaldehyde,” Solovitch was surprised to discover. “Every time I play, when I feel I have some skin in the game, I have to deal with it.” To cope, she studiously prepares. “Winston Churchill said that for every minute of a speech he’d prepare for an hour. I have to make sure every note is in my head. Then, the last day or two, just relax, meditate, go for long walks and be very thoughtful.”

A surprise reward

Jenna McCarthy, author of the new novel “Pretty Much Screwed,” found herself unexpectedly invited to do a TED-X talk in her hometown of Santa Barbara. “I had no aspiration whatsoever to be a speaker,” said McCarthy. “I’m more of a sit-down comedienne.” But she figured she would rather have a learning experience to live through than live with the regret of “what if?”

“They kept telling me ‘the E in TED stands for entertainment,’” McCarthy remembers, “But I have never been so nervous in my life. It felt like 30 degrees in the room, and I was sweating. I forgot my second line. Then I went into the zone, thinking, ‘These people are here to be entertained, not to criticize.’ And they were laughing at the right moments. I got a standing ovation. It was the most euphoric high I could imagine.”

Now McCarthy is getting work as a speaker. “I stepped out of my comfort zone, and it changed my life. I learned a great lesson: Don’t not do it without first trying to do it.”

Life and a lesson

Sharon House, now “not a thrill seeker, just accomplished” at conquering her fear of heights, went on to do a one-hour zip-line tour over the rainforest in Costa Rica and realizes the value of her feat: “I think as we get older, so much is happening that we might not be involved in — pop culture, social media, super miniskirts — so to be able to have a couple of things that make us feel good about ourselves is very powerful.”

Linda Hamilton agrees: “There’s nothing worse than thinking, ‘Here I am, and nothing more is going to happen to me.’ The brain keeps developing and learning. I think everybody benefits from that.”

ALSO:

Neuroplasticity - the brain’s ability to adapt - offers hope to those with debilitating diseases

Would you let someone zap your brain? Why ‘electronic brain stimulation’ is trending

When using social media becomes socially destructive