Is BCG a cure for diabetes? The long road to acceptance

- Share via

The first trial in a handful of humans has suggested that injecting patients with Type 1 diabetes with an inexpensive vaccine normally used to prevent tuberculosis can block destruction of insulin-secreting pancreatic cells in humans and allow regeneration of the pancreas. Such a finding, if confirmed and expanded on, could lay the foundation for freeing the estimated 1 million U.S. Type 1 diabetics from their daily insulin shots. It brings up a word that is rarely or never used in considering the disease: “cure.” Such an outcome is still a long way in the future, but Dr. Denise Faustman of Massachusetts General Hospital has already come a long way in her quest to find a new treatment paradigm for diabetes.

Researchers have always assumed that insulin-secreting cells could never be regenerated. Once they are gone, they are gone forever, the theory held. Scientists have thus focused on ways to prevent their loss -- such as by developing vaccines that will halt the immune system’s attack on the pancreas before all the cells are destroyed -- or by transplanting replacement cells from a donor. The first approach has not yet shown much success, and the second has provided only limited benefits. Insulin-secreting cells for transplants are difficult to obtain in quantity, provoke a strong immune response and require immunosuppressive drugs. They can “cure” diabetes, freeing patients from their insulin secretions, but the benefits often disappear with time.

Faustman started out as a transplanter, learning her technique from Dr. Paul Lacey of Washington University of St. Louis, a pioneer in the field. When she came to Mass General in 1985, she was confident that she could do the transplants better than other researchers and that her attempts would succeed. For one of the few times in her life, however, it turned out that she was wrong.

She decided to go back into the lab and attempt to figure out why the transplants were failing. Most researchers had studied transplants in mice in which the pancreas was artificially destroyed. Faustman decided to look at mice that, like humans, had a strong propensity to develop diabetes naturally. She found that the transplants failed in those animals just like they had in her human trials, and she eventually determined that the rodents’ immune systems were attacking the transplanted cells just like they had their own pancreases.

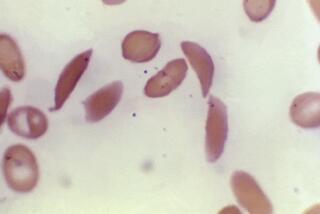

Eventually, she developed a two-pronged attack. First she injected the mice with Freund’s Complete Adjuvant, a mixture of water, oil and parts of dead bacteria that is sometimes used to increase the power of vaccines. The adjuvant overstimulated the immune cells that were attacking the pancreas, causing them to self-destruct. She also injected the rodents with BCG, known formally as bacillus Calmette-Guerin, which has been used for 80 years as a preventive for tuberculosis. It stimulated the production of another immune component, called tumor necrosis factor or TNF, that kills the cells that were attacking the pancreas.

Faustman’s goal was simply to prevent the attack on islet cells of the pancreas so that a new transplant could have a chance to take hold. To her great surprise, however, the treated mice began producing insulin again -- a finding that contradicted everything researchers believed about diabetes. Eventually, however, other labs were able to replicate her results.

In subsequent papers, Faustman showed that the new insulin-secreting cells were being produced by the spleen, a fist-sized organ that plays a crucial role in recycling blood cells. First, she demonstrated that the cure of the mice could be accelerated by injecting extra spleen cells into the animals. Then she transplanted male spleens into female mice undergoing the treatment and demonstrated that the insulin-producing cells were male in origin.

Very little research has been conducted in humans about what happens to patients after their spleens have been removed for medical reasons. But Faustman found two studies, one of British patients with pancreatitis and one of children with beta-thalassemia, in which their spleens had been removed. In both groups, many of the patients developed diabetes within five years after their surgery. These findings suggest that the spleen plays a key role in regulating glucose uptake.

Faustman had great difficulty obtaining research funds because her ideas were so contrary to the prevailing wisdom. One person who believed in her, however, was Lee A. Iacocca, the former chief of Chrysler Corp., whose wife Mary died of diabetes. Iacocca wrote her a check for $1 million and by 2006, his Iacocca Family Foundation had raised more than $11 million for her research.

She is now gearing up for a larger, phase 2 clinical trial of the technique. More information about her research can be obtained here and those interested in participating in the trials can e-mail her at diabetestrial@partners.org. But be warned there is already a long waiting list.