Fido’s arthritis drug may cure drug-resistant tuberculosis

- Share via

A pain medication so old that “Mad Men” might have concocted its first advertising campaign might be the cure for more than 500,000 people worldwide whose tuberculosis has grown resistant to front-line antibiotics, a new study says.

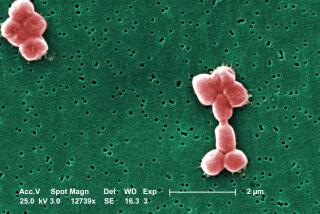

Oxyphenbutazone, an anti-inflammatory medication marketed in the 1950s as Tandearil and still used in veterinary medicine, put on a spectacular test-tube display of attacking both forms of the TB bacterium -- those that replicate and those that do not. It was one of 5,600 existing medications that researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College tested against drug-resistant strains of TB in a bid to expand the arsenal that could be used to fight the growing scourge.

The discovery of oxyphenbutazone’s apparent powers against TB, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was “completely surprising” to the researchers who uncovered them, they wrote.

Though doesn’t mean this old-line drug is ready to go out and vanquish TB worldwide, it does mean that a drug with a lengthy and pretty safe history of use in humans has shown promise against a diabolical bacteria that is growing increasingly impervious to medications long used against the debilitating and often fatal lung condition.

And it’s cheap too: In developing countries where drug-resistant TB is a growing threat, a daily dose of oxyphenbutazone would cost about two cents a day, the authors of the report estimated.

The next step, ordinarily, would be to conduct further tests on animals -- say, mice or rats. A demonstration of safety and effectiveness in animals would then pave the way for a series of clinical trials in which researchers would flesh out, in a human population, the medication’s safety and effectiveness record at various doses, in different patient populations and at different stages of the disease.

But with this particular drug candidate, there’s a problem: Mice are a poor stand-in for humans when it comes to this medication. Mice metabolize the drug much faster than humans, rendering it inactive much more quickly than would likely be the case in people.

As a result, the lead author of the study, Weill Cornell’s Dr. Carl Nathan, says the Food and Drug Administration should consider waiving the usual requirements it uses to consider approval of a new use for an existing drug. “A long track record of oxyphenbutazone’s relatively safe use in hundreds of thousands of people over decades” should be evidence enough to allow researchers to proceed with trials on humans with TB, he said.

Even if such a waiver were forthcoming, there’s the question of who would pay for the large and costly human trials that would be necessary. The makers of Tandearil have long since lost any proprietary rights to the drug’s formula, and so could not make much in the way of profits on its widespread sale. Knowing they could not recoup the costs, no profit-making pharmaceutical company would underwrite such costly trials.

In recent years, however, several philanthropies and nonprofit organzations, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, have become active in funding research and trials on diseases, such as TB, that ravage the world’s poor.

About a third of the world’s population has been infected with TB, and about one in 10 will develop symptoms of lungs shredded by the unchecked spread of the destructive bacteria. If available, drug combinations can cure the disease, but patients need to take them steadily for six months. Many do not complete the regimen, and strains of TB bacteria resistant to the drugs can roar back and spread while a patient goes on with his life.

In 2010, the World Health Organization reported, 1.4 million people died of TB, making it the world’s second most deadly infectious disease agent after HIV/AIDS.