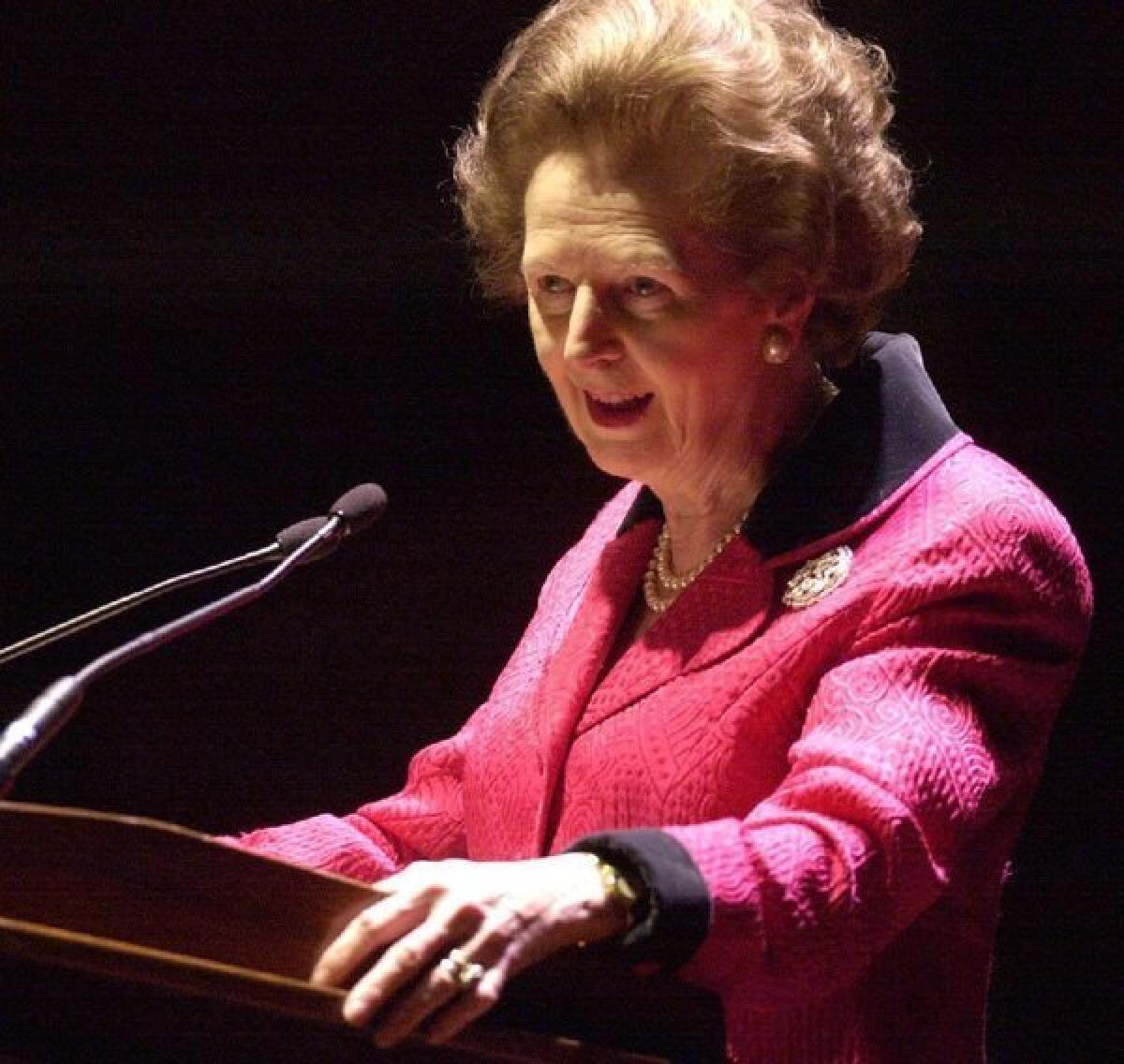

Margaret Thatcher’s dementia: cause of death or unrelated factor?

- Share via

While former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was reported to have died of stroke on Monday, few experts doubt that dementia, the disease she lived with for at least the final 12 years of her life, contributed powerfully to her demise.

“Dementia means brain failure, and brain failure ultimately causes death from immobility, malnutrition and infection,” among other downstream effects, said Dr. Paul S. Aisen, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California San Diego. Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, “is uniformly fatal,” Aisen added.

But in Great Britain and the United States, the lingering stigma associated with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias has likely led to significant underreporting of those brain diseases’ deadly impact, said Maria C. Carrillo, the Alzheimer’s Assn.’s vice president for medical and scientific relations.

Just as early AIDS patients were often said to have died of pneumonia or cancer rather than AIDS, those with dementia are frequently reported by physicians to have died of complications such as sepsis, stroke or pneumonia. Eager to overcome such stigma and reflect the disease’s full toll on society, early AIDS activists encouraged physicians to more consistently list AIDS as a cause of death.

“That’s where we are now,” said Carrillo, who said that groups like the Alzheimer’s Assn. are actively encouraging physicians to recognize and list dementia as a cause of death when it clearly has contributed to a patient’s mortality.

The stroke to which Thatcher succumbed may well be seen as a complication of dementia, said experts. Malformations and narrowing of the brain’s small blood vessels appear to be at the root of many ischemic strokes, and at the root of some forms of dementia as well, said Dr. Lon Schneider of University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

Thatcher’s apparent path to dementia -- she is said to have suffered a number of small strokes -- is common. But the process can work in reverse too: Alzheimer’s disease makes the brain’s blood vessels more brittle, raising the risk that they will burst and cause a hemorrhagic stroke, said UCLA dementia expert Dr. Liana Apostolova.

“They’re technically not easily connected,” said Apostolova of stroke and dementia. But the brain under attack from stroke clearly grows more vulnerable to processes that can lead to Alzheimer’s disease, and vice versa, she added.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, as the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States. In 2010, the latest year for which such statistics are in hand, Alzheimer’s was listed as an actual cause of death for 89,494 Americans; yet 450,000 Americans died with Alzheimer’s disease.

Severe dementia, whether progressive or not, can rob patients of the most basic life skills needed to sustain health, said Carrillo.

It’s not just that their brain disease makes them unable to exercise or remain properly nourished -- factors that can worsen existing heart disease and make a patient vulnerable to infection. Basic matters of safety -- maintaining balance, swallowing correctly, responding to pain signals that tell us we are being burned or scalded -- are compromised in those with dementia, making these patients more vulnerable to choking or falls or injury, said Carrillo. And in some cases, these secondary incidents are listed as a cause of death, she added.

But the added risk of death that comes with dementia is well documented: among 70-year-olds who have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, 61% are expected to die within a decade; among 70-year-olds without Alzheimer’s disease, only 30% will die within a decade.