Bet you can’t read this as fast as your friend can

- Share via

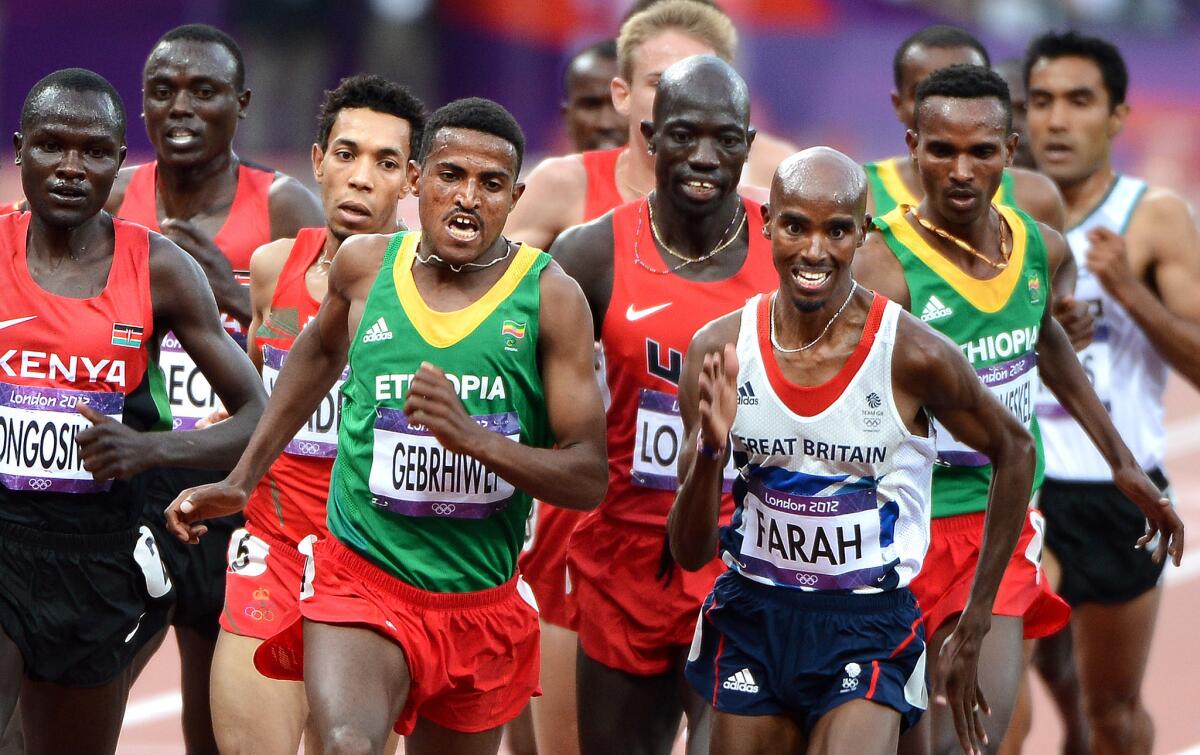

We compete for prizes ... for promotions ... for parking spaces.

We compete to see who’s fastest ... who’s strongest ... who can eat the most hot dogs in 10 minutes.

“Competition makes the world go ‘round,” write Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman in their book, “Top Dog: The Science of Winning and Losing,” to be published Tuesday.

Still, many of us are ambivalent about it. We may praise the competitiveness of some (say, certain popular athletes), disparage the competitiveness of others (say, certain obnoxious colleagues) and deny that we ourselves are competitive at all (in order to suggest what nice people we are).

All of us compete to some extent. “But we have different makeups that make us different types of competitors,” Bronson says. As it turns out, age matters. Gender matters. The gene for one particular enzyme matters. And that’s just for starters.

Age

Based on everything they knew about aging and competitive behavior, the authors of a 2011 study in the journal Psychology and Aging expected people to become steadily less competitive across their adult lives. But that’s not what they found. In fact, people tend to become more competitive until about age 50, and only then does their competitive fire gradually begin to cool.

Gender

On average, women are less eager to compete than men — at first a rather disconcerting fact for Merryman. “I’m competitive,” she thought. “Am I not supposed to be?” But there was more to the story.

As long as women have a reasonable chance of winning, they’re every bit as willing to compete as men. They just don’t like competing against all odds, whereas men seem OK with that.

Competing against all odds can pay off big-time, of course. Consider Bill Gates and Steve Jobs. But it can also backfire. One example in “Top Dog”: elite schools. The odds of being a star student in an elite school can be pretty long. “For boys,” Bronson says, “the competition can become overwhelming.” And damaging. Average boys in elite schools can end up learning less than boys of similar capabilities who attend lesser schools. But that doesn’t happen with girls. They’re apt to recognize the odds and not fight them so hard.

Genes

Competition is often stressful. Some of us thrive on that. Some of us crumble. To a certain extent, we can’t choose how we respond any more than we can choose to be tall or short. It’s in our genes. But with enough preparation and repetition, crumblers can reduce their stress — and hold things together better — in situations they face often, Bronson says.

Good labeling can help too, advises Valorie Kondos Field, who coaches women’s gymnastics at UCLA. “If you keep telling yourself how nervous you are, it can be a self-fulfilling prophecy,” she explains. “But your body gives you the same exact signs when you’re excited as when you’re nervous. So tell yourself you’re excited. You’ll do better.”

Goals

We all know people (very different from ourselves!) we consider too competitive. Scientists might identify them as hypercompetitives — people whose main goal is to beat others. Scientists distinguish hypercompetitives from those whose main goal in competition is to develop their own abilities.

Both types of people can be equally competitive — try just as hard, want to win just as much — but they differ dramatically in other ways, says Richard Ryckman, professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Maine. His research suggests that hypercompetitives have a greater need for power and control over others. They are more narcissistic but less altruistic and less respectful. People of both types can be successful, he adds.

Performance

For centuries, philosophers have debated whether competition makes us perform better or worse. In an article published last year in the Psychological Bulletin, researchers analyzed the results of more than 175 studies and found no evidence that competition affected performance either way. But they didn’t stop there. After additional analysis and three studies of their own, they concluded that when people are trying to excel — playing to win — their performance improves. When they’re trying to avoid messing up — playing not to lose — their performance goes downhill. In their original analysis, these two opposite effects canceled each other out.

“Top Dog” cites examples when playing to win can be a winning strategy — penalty shots by professional soccer players. When making the shot will save their team from losing, they succeed 62% of the time. But when making the shot will give their team the win, they succeed 92% of the time.

The last word

Overall, Bronson and Merryman conclude that most of us naturally rise to the occasion when we compete. But they also believe that most of us could probably improve. “Whether you think you’re a good competitor, or think you’re not,” Merryman says, “knowing the science of competition, understanding the mechanisms, can help you in tense situations. You’ll know what to do and how to be better at it.”