No laughs but plenty of relevance in ‘The Trojan Women’

- Share via

Now is the summer of our discontent. If you’d like a little theatrical relief from all that’s ailing America’s body politic, Anne Bogart and SITI Company are probably not your ticket.

FOR THE RECORD:

Tragedian’s name: The subheadline in an earlier version of this online article misspelled the name of ancient Greek tragedian Euripides as Euripedes.

Their new adaptation of Euripides’ “The Trojan Women,” which begins previews Thursday at the Getty Villa’s outdoor amphitheater, aims to rekindle the original political intent of a play that drives home an unrelentingly dark vision of what war does to victims and victors alike.

Bogart has long been an experimental theater eminence, often trying to counteract what she sees as the American stage’s tendency to reassure audiences and settle for low stakes. Her decision to direct “The Trojan Women” now has a lot to do with the dismaying events surrounding its premiere in 415 BC and how those times reflect the United States in 2011.

With his country fighting to maintain its wealth and empire, Euripides asked Athenians to pause to consider what the incessant Peloponnesian War with Sparta was doing to their glorious city-state.

Months before “The Trojan Women” premiered, Athens had slaughtered every man and enslaved every woman and child on the neutral island of Melos for refusing to take its side.

Meanwhile, war drums were beating. Athens was equipping a fleet to invade far-away Sicily as Euripides’ play was debuting, according to Oxford classicist Gilbert Murray’s introduction to his 1915 translation. Based on Homer’s epics, “The Trojan Women” gives an anguished portrayal of the defeated Queen Hecuba and the remnants of her royal house being tormented by conquering Greeks who practice a cold-hearted realpolitik. The play won second prize at that year’s festival of Dionysus but did not deter the invasion. The Sicilian campaign — the epitome of a war of choice — was a disastrous turning point, according to historian Donald Kagan’s “The Peloponnesian War,” spelling eventual doom for the “golden age” of Athens and hastening its permanent exit as an important player on the world stage.

With America engaged in its own long, grueling wars, Bogart wants audiences to consider whether history can repeat. The not-so-veiled warning Euripides issued in “The Trojan Women” was that a beacon of democracy and culture could waste its treasure and throw away its moral standing.

“Sounds kind of familiar, doesn’t it?” Bogart said recently, during a break in a rehearsal. “I don’t think you can experience this play without thinking about the unconscionable wars we’ve perpetrated and the consequences for the future. What’s happening these days could be the end of any affluence in this country.”

Bogart has a certain standing to opine about American wars. Her father was a career Navy officer and her maternal grandfather, Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, commanded the U.S. forces at the pivotal Battle of Midway, turning the tide against Imperial Japan during World War II.

Given their druthers, the folks in charge of the Getty’s ancient theater program would have preferred something a little lighter. Staging a major outdoor production of an ancient play each September — the budget for “The Trojan Women” is about $400,000 — they like to alternate season by season between comedy and tragedy. This year was supposed to be comedy’s turn.

Norman Frisch, head of the theater program, said he’s long been a fan of Bogart’s and relished the chance to bring in SITI Company, whose 20th anniversary is next year. He asked if she would consider doing a different play by Euripides. The problem wasn’t that “The Trojan Women” is too pointed, Frisch said, but that it’s widely acknowledged to have serious dramatic drawbacks. The original script is notoriously bleak and monolithic — just one disaster after another for the title characters.

“In candor, one can hardly call ‘The Trojan Women’ a good piece of work,” Richmond Lattimore wrote in an introduction to his 1950s translation of the play, “but it seems nevertheless to be a great tragedy.”

Never mind the drawbacks; Bogart and SITI Company had their hearts set on “The Trojan Women,” and Frisch says he knew better than to get in the way of artists with a passion.

The new adaptation by Jocelyn Clarke, a male dramaturge from Dublin who has worked frequently with SITI, aims to mend Euripidean flaws with fresh inventions. One is a climactic confrontation between Hecuba and Odysseus, whom Euripides had left offstage as the unseen agent of the Trojan women’s degradation.

Bogart opened rehearsals to the Getty’s antiquities curators, wanting their input. She and Clarke had planned to dispense with the play’s choral odes — philosophical poems that don’t advance the action or deepen the characters.

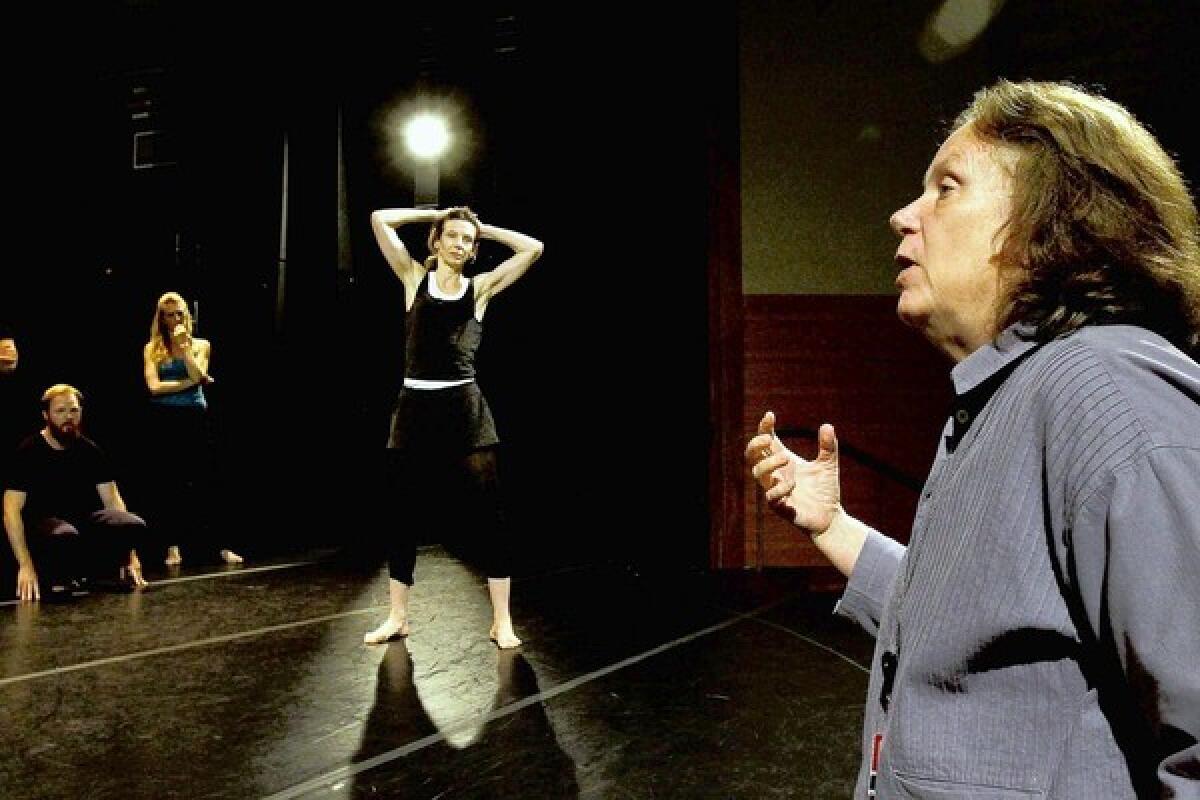

“Because of the curators’ passion for the odes, we put them back in the play,” said Bogart, who at 59 is tall, big-boned, leonine and far from flamboyant. Her uncoiffed hair and attention-deflecting clothes are a sort of contrarian statement, making her come off more like a throwback to frontier women than the avant-garde artiste one might expect. The in-house classicists’ complaints were a godsend, she said, because the restored odes provide valuable breaks from the play’s onslaught of bereavement.

SITI Company began in 1992, eight years after Bogart first made her mark with a New York production of “South Pacific” set in a rehab ward for psychologically damaged war veterans. While comparable, long-running experimental theater companies such as Mabou Mines and the Wooster Group have had some intersections with fame, SITI’s nine-member acting company boasts cohesiveness but little exposure on Broadway or on screen (the initials are for Saratoga International Theater Institute, after the company’s upstate New York summer quarters, where actor training remains a key part of its mission).

Jefferson Mays, a SITI member during the 1990s who went on to win a best actor Tony Award in 2004 for “I Am My Own Wife,” is the only prominent alum; Bogart considers founding member Ellen Lauren, who plays Hecuba, “one of the most extraordinary actresses of our time but better known in Europe and [Japan]. The joke right now among the actors is, ‘We’re in L.A. now, maybe we’ll get discovered.’”

SITI has won its share of plaudits, with works such as “bobrauschenbergamerica” by playwright Charles L. Mee, a company member. But its main calling card is its overall approach rather than any given production.

Bogart has been a leading advocate of acting from the neck down, making how actors move onstage as important as what they say. She’s been the leading exponent — though not, she hastens to say, the creator — of a dance-rooted physical acting technique known as Viewpoints.

To Travis Preston, dean of CalArts’ School of Theatre and a keen proponent of experimental work, Bogart and SITI “have been an exceedingly important icon for the whole adventurous-theater world, because they have been able to endure in an environment that is often exceedingly hostile to the concept of an ongoing company.”

From Shakespeare and Molière on down, Preston said, “it was always understood that the significant work in theater history emerged from people who worked together collectively over time rather than emerging from one-off relationships.” But such cohesiveness is expensive and therefore uncommon on the American scene. SITI, which cobbles together about $1 million a year from performances, teaching fees and donations, helps carry its torch.

Asked to point to the company’s most important accomplishments, Bogart doesn’t talk about particular productions or credits but the implications of having kept up a collaborative, democratic way of working over the long haul.

“Our band could be your life,” sang the Minutemen, the 1980s L.A. punk-rock trio whose example of purity and comradeship may have mattered more than its highly praised music. Bogart sums up the 18-member SITI Company by saying much the same thing.

“The way actors treat one another and respect one another proposes a way that a society might work,” she said. “When you watch SITI Company, you’re watching a proposal of how people might be together. Can we get along, and how can we get along better? That’s the great democratic question that theater is about.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.