The hidden story behind SoCal’s whimsical playground filled with monsters

- Share via

Southern California’s monsters are hidden in plain sight. I’ve lived in L.A. for more than four decades and only recently discovered Minnie the whale, Stella the starfish, Ozzie the octopus and dolphins Flipper, Speedy and Peanut in Vincent Lugo Park. La Laguna de San Gabriel playground (some call it Monster Park; some call it Dinosaur Park) opened in 1965 with 14 midcentury slides and climbable creatures. About 15 years ago, the city of San Gabriel deemed the structures unsafe and planned to demolish them.

Then a funny thing happened.

The little kids who had climbed up and slid down the backs of whales and sea serpents for years were now adults who cherished the whimsical genius of little-known sculptor Benjamin Dominguez. That’s right — the monsters had loving friends, some in high places, who didn’t forget their childhood playground when it was threatened by the wrecking ball.

Eloy Zarate, a history professor at Pasadena City College, was one of them. “It’s a time capsule of parenting, a time capsule of how kids used to play,” said Zarate, who grew up in San Gabriel and played at La Laguna. “It’s such a different place. So when they said they were going to demolish it, my wife [Senya Lubisich] and I looked at each other and said we would do absolutely everything possible to be able to save [it]. If we have to put up our house or whatever else — we just firmly believed that San Gabriel is not San Gabriel without La Laguna.”

Zarate wasn’t alone. He co-founded the nonprofit Friends of La Laguna and eventually enlisted the help of L.A. County Supervisors Kathryn Barger and Hilda Solis, who also remembered playing on Dominguez’s creatures. Fast-forward to today: La Laguna is on the National Register of Historic Places. Over the course of more than a decade, the group raised almost $700,000 — with help from the Annenberg Foundation, the Los Angeles Conservancy and county supervisors, among others — to preserve the playground that cost $12,000 to build in 1965. One more piece, a lighthouse that doubles as a slide, needs to be restored. Donations can be made through the Friends of La Laguna website.

La Laguna is not the only place with Dominguez’s works. His creatures can be found around Legg Lake at Whittier Narrows Recreation Area in South El Monte (Solis allocated money to preserve this site and invited Dominguez’s descendants to a ceremony with the restored creatures), the Atlantis Play Center in Garden Grove and sites in Nevada and Texas.

But his story was almost lost to history. Dominguez was a well-known Mexican concrete artist before he came to the U.S. in 1956 at the age of 62. La Laguna was his last work, completed when he was 70. Yet when Zarate began looking into the story behind the sculptures, he found references to “the Mexican” instead of Dominguez being identified by name, even though he is up there with Isamu Noguchi and Pablo Picasso as distinguished artists who also designed playgrounds.

La Laguna stands as a testament to his legacy in Southern California. “We stayed true to the vision of Benjamin Dominguez and stayed true to the vision of what San Gabriel had in mind in the 1960s,” Zarate said. By all means, take time to visit the monsters — and revel in the imagination of an almost-forgotten immigrant artist.

5 things to do this week

1. Ski or snowboard in the Polar Bear Run to raise funds for children affected by the war in Ukraine. Mountain High ski resort near Wrightwood invites all who make a $25 donation to UNICEF USA to a day of spring skiing. The donation gets you a single-day lift ticket (usually $109) to participate in the Polar Bear Run at 1 p.m. Sunday. Skiers and boarders are encouraged to wear white swimsuits (the polar bear theme). The event is limited to the first 100 participants who show up starting at 8 a.m. Bring an ID, a receipt for your online donation and a liability form found on the website.

2. Turn out the lights during Earth Hour on Saturday. Earth Hour 2022 will take place at 8:30 p.m. (wherever you are on the planet) Saturday. What’s the point? “[W]e were trying to find a way to unite hundreds of millions of people to protect the planet, so we came up with a symbolic act of switching lights off as the first step in the Earth Hour journey,” creator Andy Ridley previously said in a media interview. Locally, the solar-powered Pacific Wheel on the Santa Monica Pier will douse the lights. Last year, people from 192 countries and territories participated in the grassroots environmental act. In past years, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Las Vegas Strip and Rome’s Colosseum have gone dark in solidarity. What should you do during the hour in the dark? Play a board game, go on a night hike or have dinner by candlelight.

3. Learn what flowers are trying to tell you on this night hike. Floriography might be described as the secret language of flowers. People in the Victorian era used different flowers to send secret messages to lovers and friends. Daisies meant purity; jonquils, respect and friendship; and narcissus, sweetness and self-love. The Los Angeles County Arboretum & Botanic Garden in Arcadia invites all to learn more about “the subtle art of communication through flowers” on a night hike from 7:30 to 9 p.m. Saturday; tickets cost $20 to $25. Register here.

4. Believe it or not, it’s Milky Way season. Go see it. NASA describes the Milky Way as “a large barred spiral galaxy” that “appears as a milky band of light in the sky when you see it in a really dark area.” Now that you know what you’re looking for, the next step is to know when and where to go to best see the galaxy. Capture the Atlas says the sweet spot is between midnight and 5 a.m. — and on nights with a new moon — from February to October. (The website has a downloadable Milky Way calendar for best viewing times in the Southwest.) Times Community News photo editor Raul Roa got an early jump with this photo taken at Joshua Tree National Park in March. He set up at 1 a.m. and started shooting photos around 3 a.m. when the Milky Way rose. Here are tips on how to see and/or photograph the Milky Way. Mark your calendar for the Night Sky Festival on Sept. 22-23 at Sky’s the Limit Observatory in Twentynine Palms.

5. Take a free bird-watching walk with a pro. Spring is a special time for bird-watching, when migrating species swing through SoCal. The best way to learn is to go with a guide. The Palos Verdes/South Bay Audubon Society is hosting a birding walk for kids and newcomers at Madrona Marsh in Torrance on Saturday, and a second walk at Ken Malloy Harbor Regional Park in Harbor City on April 3. Each event is limited to 12 participants; register here. It’s a good opportunity to learn a new skill and to explore two little-visited parks.

Wild things

The rose-veiled fairy wrasse (Cirrhilabrus finifenmaa) is having a moment. The rainbow-colored marvel that lives in the waters off the Maldives was once lumped in with a different fish. “What we previously thought was one widespread species of fish is actually two different species, each with a potentially much more restricted distribution,” lead author and University of Sydney doctoral student Yi-Kai Tea said in a statement. The discovery is the first to be described by a Maldivian researcher, and “the first species to have its name derived from the local Dhivehi language, ‘finifenmaa’ meaning ‘rose,’ a nod to both its pink hues and the island nation’s national flower,” according to a California Academy of Sciences news release. The San Francisco-based academy’s Hope for Reefs program collaborated on the discovery with the University of Sydney, the Maldives Marine Research Institute and the Field Museum.

Soviet-era refugee Jenny Yurshansky has upended everything you think you know about “invasive” or “non-native plants.” The Lincoln Heights artist created a work that asks us to see beyond what are sometimes “blacklisted” flora and instead think about the trauma of refugees arriving in countries with unrecognizable landscapes. The artist has produced a web-based audio guide that tells stories about plants not typically found in California, like the Canary Island date palm. “These are the stories of generations of migrants,” Times staff writer Deborah Vankin writes of Yurshansky’s work. “What these plants offer us reflects a landscape that is cultural as much as it is botanical, everything from humble weeds to deliberate landscaping. The experience is meant to familiarize the audience with these plants to better understand the ways in which the landscape is not only botanical but also historical and cultural — the result of human settlement.” You can listen to an audio tour that puts plants in context as part of Yurshansky’s solo exhibition, “A Legacy of Loss: There Were No Roses There,” on view at American Jewish University through May 12. Read the full story here.

The red flag

Imagine losing 95% of your personal habitat (places where you could live and thrive) in the last 30 years. That’s pretty much the plight of the San Bernardino kangaroo rat, so named because these 3-inch creatures hop like kangaroos. “Today, the rat exists in three isolated populations, one of the largest of which clings to existence on 5,000 acres of alluvial floodplains on the southern flanks of the San Bernardino Mountains,” an L.A. Times story says. Endangered species protections should help, right? With a dwindling population and loopholes in the law, the outlook for the rat’s future — and other species in the same boat — isn’t rosy.

P.S.

Did you know California has the oldest state park network in the U.S.? The first California State Parks Week will showcase the agency’s 279 sites with in-person and virtual events June 14-18. Each day’s activities carry a theme. June 18, for example, is Partnership/Volunteer Day, which means you can help fix up trails at Topanga State Park in Topanga, restore dune areas at Carpinteria State Beach in Carpinteria or clean up trails at San Onofre State Beach in San Clemente. Go to the California State Parks Week website for a list of events. Along with the agency, State Parks Week is sponsored by Save the Redwoods League, Parks California and the California State Parks Foundation.

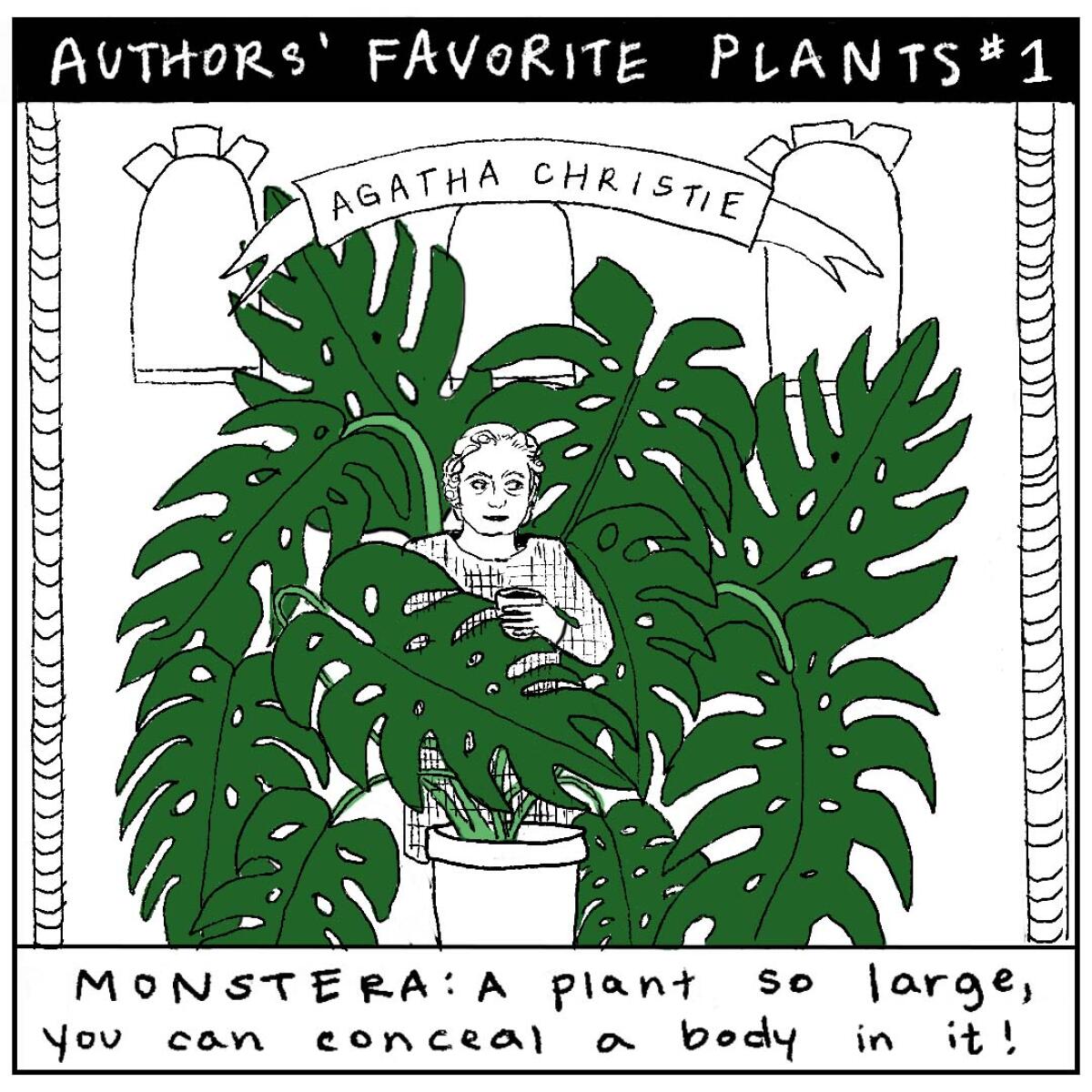

Any flora with the word “monster” in its name gets my attention. I’m talking about the common philodendron called Monstera deliciosa, native to the tropical forests of southern Mexico — and plenty of Angeleno homes. It’s easy to grow, has enormous leaves and just might be Agatha Christie’s houseplant of choice (perfect place to hide a dead body). That’s the opinion of illustrator Kelsey Davenport, who paired authors with what she thinks may have been their favorite plants. See how many of these species you can find while visiting friends around SoCal.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Send us your thoughts

Share anything that’s on your mind. The Wild is written for you and delivered to your inbox for free. Drop us a line at TheWild@latimes.com.

Click to view the web version of this newsletter and share it with others, and sign up to have it sent weekly to your inbox. I’m Mary Forgione, and I write The Wild. I’ve been exploring trails and open spaces in Southern California for four decades.

Get ready for the Festival of Books

Sign up for the Book Club newsletter for a guide to the events, authors and other highlights of The Times’ annual book festival, returning in-person April 23-24 to the USC campus.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.