L.A. County sheriff’s deputies who lied continue to draw paychecks

- Share via

The sheriff's deputy needed to be fired, his supervisor decided.

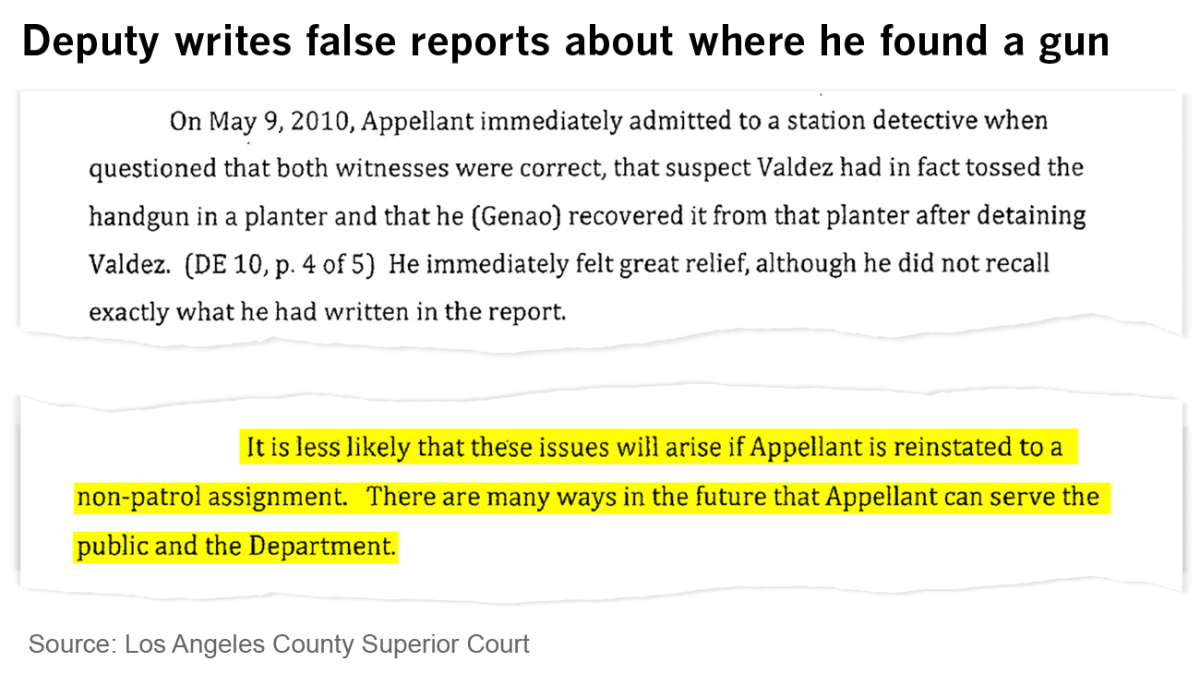

Daniel Genao was popular with his colleagues and had never been in serious trouble before.

But he had made false statements on police reports, writing that there was a gun in a suspect's waistband when the weapon was actually behind a nearby planter.

From then on, Genao's testimony in court would be questioned, Chief Thomas Laing noted, according to county records. More broadly, Laing said, Genao's actions had undermined the criminal justice system.

Nearly four years later, Genao continues to draw a county salary. The Los Angeles County Civil Service Commission reinstated him, even though he had pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor charge of filing a false police report.

Sheriff Jim McDonnell is fighting the case and others like it in court, saying he is determined to keep lying deputies off his force.

Since taking office in December, McDonnell has made honesty among his 9,000 sworn deputies a centerpiece of his reform agenda. He has tightened the penalties for lying on the job, fired deputies who made false statements and is reviewing the assignments of those found to have lied in the past. Some could be required to work under special conditions, such as recording all their interactions with the public.

McDonnell's tough approach contrasts with that of former Sheriff Lee Baca, who let some proven liars off with remedial classes. Baca himself pleaded guilty in federal court last month to lying to federal authorities and faces up to six months in prison as part of his plea agreement with prosecutors.

Establishing clear ethical boundaries is especially important as the department emerges from a period of scandal, with more than a dozen former employees convicted of crimes including lying and beating a jail visitor, McDonnell said in interviews with The Times.

He said there is no place in his department for the most egregious liars. Assigning them to desk jobs is not a solution because every deputy should be ready to testify on the witness stand, he said.

"My question is, for someone who is proven to be untruthful or lacks integrity or committed acts of theft, insubordination, those kinds of things, where can I put someone like this?" McDonnell said. "Where can I comfortably deploy people where we don't have that level of trust?"

My question is, for someone who is proven to be untruthful or lacks integrity or committed acts of theft, insubordination, those kinds of things, where can I put someone like this?

— Sheriff Jim McDonnell

But to fully implement his strict regime, McDonnell must contend with the Civil Service Commission, a five-member body appointed by the L.A. County Board of Supervisors that adjudicates discipline cases of county employees. In the last year, the commission has reinstated Genao as well as a deputy who lied about whether he had tried to take a photo under a woman's skirt and another deputy found to have falsely asserted that he had not witnessed a colleague beat up a jail inmate.

McDonnell's efforts to challenge those decisions and two others involving false statements mark a significant change from the past. In the previous five years, the Sheriff's Department did not appeal any civil service decisions of any type, according to department officials.

The number of deputies with documented histories of dishonesty could be in the dozens or hundreds and possibly includes some high-ranking supervisors, said Executive Officer Neal Tyler, McDonnell's top aide.

Even if he wins the court appeals, McDonnell cannot completely clean house. Because of contractual protections, he cannot get rid of proven liars he inherited from the Baca era.

In the landmark Brady vs. Maryland case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that prosecutors must turn over exculpatory evidence to the defense. Local prosecutors keep a so-called Brady list of officers with credibility issues, which defense attorneys can use to undermine the officers' testimony, potentially derailing criminal cases.

At the Los Angeles Police Department, where McDonnell spent much of his career, lying under oath or on an official report almost always costs an officer his or her job if the lie is material to the case, said Cmdr. Stuart Maislin, who is in charge of internal affairs.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

An LAPD officer who is fired by the chief for lying but reinstated through the appeals process is typically placed on long-term desk duty.

"Once we prove something is a false statement, it's almost a kiss of death" for the officer's career, Maislin said.

Under Baca, a cornerstone of the Sheriff's Department's discipline system was the use of remedial classes instead of suspensions. If deputies learned why the behaviors were wrong, Baca reasoned, they would be less likely to re-offend.

In a 2013 report, a department watchdog said classroom time was not adequate punishment for some deputies who made false statements, including lying on official records.

"There are far too many instances of the department being lenient toward members who withheld or obscured the truth," Special Counsel Merrick Bobb wrote in the report.

Full coverage: L.A. County jail system under scrutiny

But advocates for sheriff's deputies say the issue is not black and white.

Sean Van Leeuwen, vice president of the Assn. for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs, a union representing deputies, criticized McDonnell's "one size fits all" approach to honesty.

"Was this a bad act or was this a bad heart?" Van Leeuwen said. "Did you do something wrong because you made a mistake, or was this really a bad act?"

Both the LAPD rules and the new sheriff's policies include a range of discipline, up to and including termination, for making false statements. McDonnell said he does consider the deputy's intent and the seriousness of the lie in deciding the punishment.

Still, McDonnell is cracking down. In his first year in office, 90% of deputies found to have made false statements were fired. In the preceding three years, half were fired, with the other half receiving suspensions or demotions, according to department statistics.

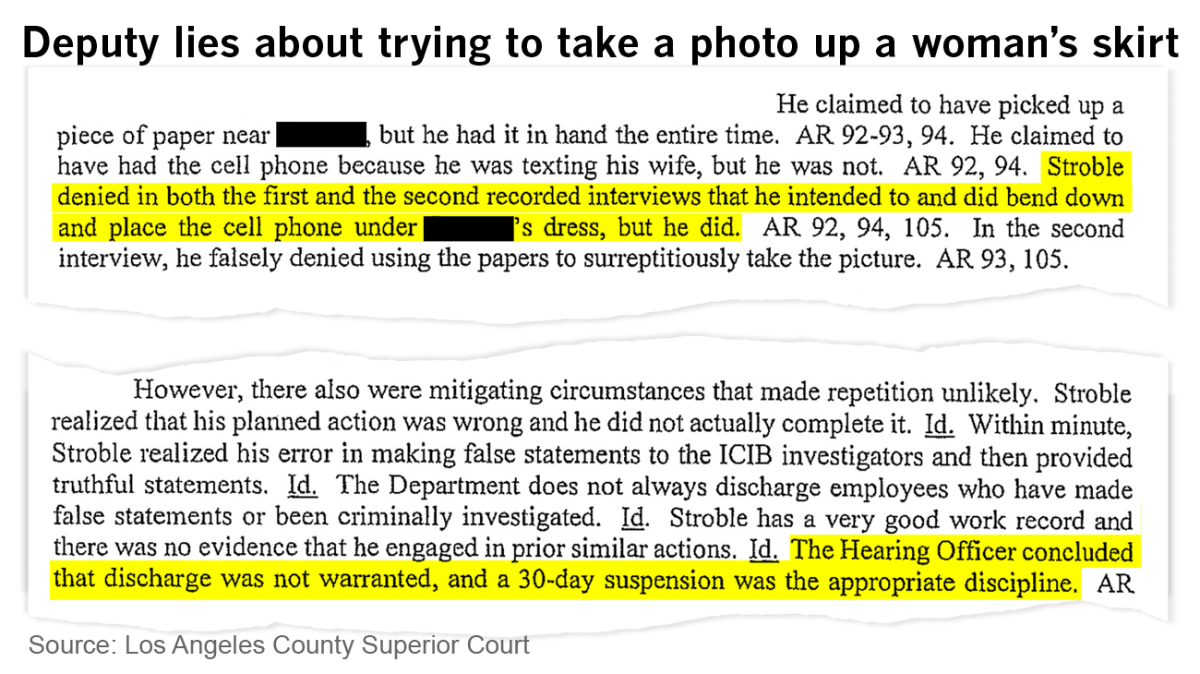

Deputy Steven Stroble was on duty at the Alhambra Courthouse on June 14, 2011, when he reached under a woman's skirt to take a photo with his cellphone, according to a civil service hearing officer's report filed in court.

In an initial interview with sheriff's investigators, he denied being in the building that day. He later admitted he was in the clerk's office but claimed he was picking up a piece of paper near the woman while texting his wife on his cellphone, the report said.

The investigators urged him to tell the truth, because the incident had been captured on video cameras inside and outside the clerk's office. Stroble denied that he tried to photograph under the woman's skirt but said he had intended to take a photo of her leg to send to his brother. He said he stopped as he was leaning over, realizing it was a stupid thing to do, the report said.

In March 2012, Stroble pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor charge of photographing under a person's clothes for the purpose of sexual gratification.

The Sheriff's Department fired Stroble. But the Civil Service Commission reinstated him, noting that he did not actually take the photo, that he owned up to the lies and that other employees have kept their jobs despite making false statements.

In November, a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge agreed with the department that the deputy should be fired. Stroble is appealing and remains on leave, with pay.

Genao, the deputy who wrote false reports about the gun, said he was traumatized because of his fear that the suspect he encountered was armed. Stress and confusion, Genao said, caused him to write that he found the gun on the suspect rather than behind the planter, according to a civil service hearing officer's report filed in court. Genao insisted that he did not intentionally lie, the report said.

The hearing officer concluded that dismissal was excessive because Genao admitted to the false statement and was a popular, well-respected deputy. Other deputies have ended up on the Brady list yet remained on the job, and Genao could work a non-patrol assignment, the hearing officer noted.

The Civil Service Commission voted to return Genao to duty with a 30-day suspension. The Sheriff's Department has put him on leave, with pay, while it appeals.

In a third case being challenged by McDonnell, Deputy Mark Montez said he did not see or hear another deputy punch an inmate seven times at Men's Central Jail on Sept. 27, 2010, according to a civil service hearing officer's report filed in court.

Video showed Montez was standing nearby when the beating occurred, according to the report. Montez had to have heard the inmate being beaten, so his denials were not credible, the hearing officer concluded.

Montez also said he was unaware that his colleague later bashed the inmate's face against the wall. But afterward, he was seen on video with the colleague, motioning with his arms as he looked at the wall, which had blood on it, the report said.

The Civil Service Commission reinstated Montez, noting that other employees who were nearby and denied knowledge of the beatings received lesser punishment. The department is appealing, and Montez remains on leave, with pay.

Greg Z. Kahwajian, president of the Civil Service Commission, said the panel's decisions reflect the disciplinary standards set by the Sheriff's Department. The commission has sometimes found it compelling when deputies have pointed to others who committed similar offenses and kept their jobs.

Among those who kept their jobs is David Anthony Hernandez, who pleaded no contest in 2009 to filing a false police report.

To justify searching a car, he claimed he had found several arrest warrants for people connected to the vehicle, according to court records. But computer records showed he hadn't looked up the warrants until after he had found cocaine and arrested the suspect.

Hernandez was placed on paid leave after the criminal charges were filed, returning to duty after an administrative investigation, a department spokesman said. Officials declined to say what punishment Hernandez received, citing state confidentiality laws.

Hernandez could not be reached for comment. He is still employed as a patrol deputy.

Twitter: @cindychangLA

ALSO

How an emergency declaration over L.A.'s homeless became a game of 'hot-potato keep-away'

Cal State faculty, students expected to press trustees on pay raises, tuition at Long Beach meeting

Oil and gas firm reactivates long-idle wells near L.A. school after residents seek to plug them

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.