From the Archives: Green Card Marines: A Guatemalan orphan — artistic, poetic — sought a better life in the U.S.

- Share via

On this Memorial Day weekend, we take a look back at our 2003 series on Green Card Marines.

The war in Iraq drew attention to the growing number of noncitizens in the U.S. military -- about 37,000. Ten were killed during the war, seven from California. Most were Latino. This is the first of four portraits of Green Card Marines who gave their lives.

After all he had seen, Jose Antonio Gutierrez might have been forgiven for telling the lie.

When he was 3, his mother withered to 66 pounds from malnutrition; two years later she died in a Guatemala tuberculosis ward. Jose was left to his father, who forced his son to beg for change and scavenge for food, then died a drunkard's death with the 8-year-old boy by his side.

Jose eventually made the 2,000-mile trek from Guatemala to Los Angeles, promising the sister he left behind that he would become an architect and design great buildings.

So, on a spring morning six years ago, the baby-faced kid with big ears sat at a shelter for the homeless in Hollywood and, through his rotten teeth, told a daring lie.

Social worker Rafael Angulo asked Jose how old he was. Jose said 16.

He had plenty of reason to hide the truth. Adults who cross the border illegally are subject to deportation. A juvenile with no family could probably stay.

The social worker studied the smooth young face and wanted to believe the boy. Two weeks later, Jose was placed in his first foster home.

The boy, it turned out, was 22.

The lie changed everything. It got him a green card, and the green card got him into the Marines, and the Marines took him to the Iraqi port of Umm al Qasr, where he was killed the afternoon of March 21, one of the first U.S. servicemen to die in the war.

The life and death of Jose Gutierrez is the story of an improbable American hero, a Guatemalan orphan slain fighting for his adopted country. It is a story that has been told around the world.

But now the government says that Lance Cpl. Jose Gutierrez ran out of a building that had been secured by Marines and was shot by mistake -- apparently killed by friendly fire.

Jose was assumed to be an enemy soldier when he was shot, his commanding officer wrote in a letter of condolence to his sister, Engracia. "Obviously, this was a tragic accident."

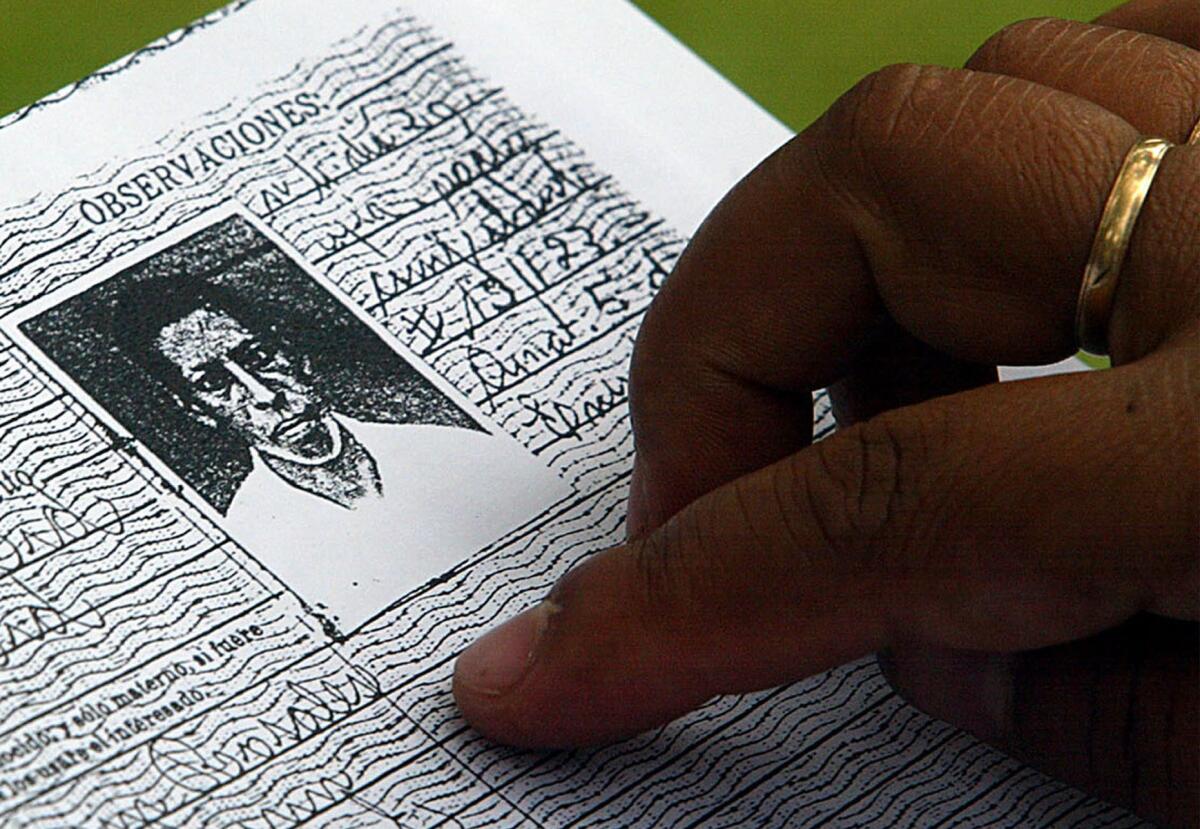

Jose had always wanted to be famous, Engracia says, a candle illuminating a gallery of his photos in her tiny bedroom in Guatemala. In one, he's smiling like a tourist in San Diego. In another, he stares out with no smile in his Marine jacket and cap.

He was a boy who inspired others to help him and, as he moved from the streets to an orphanage to jail to foster homes, Jose kept looking for a place that would give him order. He found that place in the Marines. His sister said he had enlisted out of gratitude to the United States for having given him a second chance.

But as war loomed, he was haunted by second thoughts.

"I understand everything we've been taught," Jose wrote to a friend. "The only thing I do not understand is, why wars? Why do we fight against other human beings if, at the end of our time -- friends or enemies -- we all end up in the same place, buried in cemeteries and many times forgotten."

Tragedy Upon Tragedy

When he was a young child, his days would begin with the smoke of the kindling wood, his mother hovering over the pungent fire with a bowl of fresh corn dough beside her. She would dip her hand into the mound of masa and place a thin round cake on the clay pan that sizzled above the fire. Then, one by one, she would set the hot tortillas in a basket and head on foot to the central market, making about $2 a day.

Jose's mother, Maria Ernestina Gutierrez, and his father, Jose Fidelino Sirin, settled in the sugar town of Escuintla. Their first child was a daughter named Engracia. Jose Antonio was born five years later, on Dec. 1, 1974. Maria had him baptized at the Church of the Immaculate Conception, a few paces from the market where she hawked her tortillas.

The boy grew up with the sound of his mother's cough, a rattling deep in her lungs for which the family blamed the smoke of the tortilla fires and cold water baths. Her condition, Engracia recalls, seemed to worsen with the stress of a third child, a girl named Maria Ismelda.

Jose's mother was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and the only public sanitarium that could treat her was in Guatemala City. The family uprooted itself and moved to the northern fringes of the capital, to a neighborhood of hovels that clung to the side of a gorge above a rancid river known as Las Vacas. From their one-room adobe shack, little Jose and his older sister could see the black vultures swooping down into the water to dine on the refuse from slaughterhouses upstream.

They had nothing. We had very little ourselves, but we did what we could for them. What could we offer? A few tortillas?

— Consuela Ruiz Ayala, neighbor

Their father was often sullen and drunk and would leave the house for hours to drink. With their mother hospitalized, the children grew up fending for themselves. Their father would send Jose out to beg, recalls Consuelo Ruiz Ayala, who lived nearby.

"They had nothing," she says. "We had very little ourselves, but we did what we could for them. What could we offer? A few tortillas?"

Struggling to quiet the cries of baby Maria, Engracia offered her breast to her sister. There was no milk -- she was still a child herself -- but the sucking brought the little one some comfort. One day in the rainy season, the father left the house with 2-year-old Maria and didn't return. Shortly after daybreak came a knock on the door.

Engracia says a neighbor told her the bad news. Their father had lost Maria on the way home from a night of boozing. The toddler was found in a puddle of rainwater.

"My sister died that day," Engracia says, years later, tears in her eyes. "I always blamed my papa for her death."

From then on, the weekly visits to the TB hospital began and ended the same way: their mother wondering why her youngest child wasn't with them. Their father would make excuses, Engracia recalls. Little Maria was staying with the neighbors.

It was left to Engracia to tell her mother the child had died; the father couldn't find the courage. In the months that followed, the mother was desperate to go home, according to hospital records. She feared for Jose's safety, knowing that her husband was responsible for the death of their youngest child. But she died after two years in the sanitarium, her age listed as 32.

The family abandoned the shack in the gorge. Engracia, furious with her father, moved in with a family that owned a variety store. She had missed so much school that the 11-year-old girl was enrolled in the first grade. Jose Antonio, 6, was left with his father, wandering from bar to flophouse.

The father rented a room in the shadow of a 19th century church, and the three reunited as a family for a time. But his nights out left his children to beg for food at the bakery across the street.

Their hunger finally led them to run away, back to the gorge, back to the shantytown above the filthy river where their old neighbors would at least take pity on them. They were living alone, a 12-year-old sister and her 7-year-old brother, and the food they scrounged was never enough. One day, Engracia found that Jose had been scavenging for scraps in a heap of garbage. The news enraged her.

We're not that kind of people, she says she screamed. Then she struck him, and he ran away, seeking his father.

Sister and brother wouldn't see each other for 11 years.

Trolling for odd jobs, the father left Jose in the care of a street vendor named Clotilde Lopez, who ran an open-air food stand along the main drag. Lopez would give the boy something to eat and then watch over him as he slept in the shelter of her stall.

Engracia found a home with a family in a nearby neighborhood where she lived as their domestic for the next 18 years. Their father dropped dead in a cheap hotel room in 1983, with Jose by his side.

Jose and Engracia were now real orphans.

"I come from a place where the angels reside in misery. They are clothed in filth, and they devour dreams," Jose wrote in a letter. "Don't you see that loneliness terrifies me?"

An Oasis -- While It Lasts

The four teenage boys slipped out of the dark hall and tiptoed along the lush grounds of the rambling colonial compound. It was movie night at the orphanage, and they had other ideas. The orphanage, home to Jose Antonio and 124 other boys, was an island of calm and beauty amid Guatemala's 35-year civil war. The grounds were an old coffee plantation, and the Spanish-style buildings had once been a luxury hotel.

Jose and his friends threaded their way through stands of orange trees and headed to the field where the horses grazed. They reached the pasture in the brisk highland air and mounted bareback. John Rodas, one of Jose's buddies, remembers the exhilaration as his horse began to bolt through banana groves and rows of coffee plants.

"I just recall riding and riding, feeling free as could be," he says. "It's something that stuck with me all these years."

Jose's ability to think of himself as more than a street kid, his friends in Guatemala say, came from the years he spent at the former Casa Alianza, outside the town of Antigua. The orphanage was a project of Covenant House, a Catholic program for runaways that was founded in New York City. The man in charge was Patrick Atkinson, a North Dakota farm boy and lay missionary who became a substitute father to the boy he knew as Tono.

The boys raised turkeys and tended to the garden that provided fresh vegetables for meals at the orphanage. They swam in the pool and took field trips to Maya ruins, the beach and the volcano that rose outside their windows.

"He was a very alive kid. Yet he had this sadness inside of him ... this hole," says Atkinson, who was drawn to the boy's intelligence and compassion. "He would see a poor woman on the street and tell me, 'Stop. Give something to that woman over there. She needs help.' "

Jose grew close to another orphan, Diego Raymundo de Leon, whose mother and father had been killed by the military. The two friends tried not to dwell on their pasts, but sometimes it was hard not to talk about their mothers.

"He was the only one I could cry with, and maybe I was the only one with whom he could cry over and over again," Raymundo recounts.

Even in the comfort of the orphanage, Jose could not let go of the ways of the street. He would sneak into the groves and pick oranges, Raymundo recalls. Jose would carry them in his curled-up shirt back to the coffee fields, where he would find a hiding spot and sit and watch the birds. "He'd eat as many oranges as he could," Raymundo says. "The ones he didn't eat he would bury and come back and get them later."

Inmate, Then Immigrant

When he turned 15, Jose outgrew the orphanage. Outside the walls he floundered, dropping out of school and drifting from one foster home to another. He honed his skills as a hustler and thief, and also his sensibilities as an artist.

Jose was a boy looking for symbols, and the rose became his emblem. He drew its petals and wrote about its beauty.

He became infatuated with a 14-year-old schoolgirl, Paola Urizar. He would spot her walking home from classes and hand her intricately drawn roses and love notes. "You are more beautiful than the roses," he wrote. She found his approach charming.

"He never disrespected me or tried to kiss me or anything like that," Urizar recalls.

But after he began slipping notes to her through her window, Jose's advances infuriated her father. He told her she was too young for such things, she remembers. Besides, her father told her, when it was time to marry, she would not marry someone like Jose.

Jose didn't protest, she says.

"He told me that he was an orphan, that he was all alone in the world and looked for refuge in another person. He seemed to be a little obsessed by that idea of finding refuge in a person, of finding family."

To feed himself, Jose took candles from merchants and bicycles from other kids. He was caught stealing with another boy from the orphanage, Martin Calan, and they were thrown into a dank jail known as La Granja, the Farm.

As he had done so often, Jose, now 18, got by on his wits -- and a lie. That first night, Calan recalls, the tattooed leader of the prison gang threatened the two boys. Jose instantly invented a tale that earned them, not only protection, but admiration: He said they had just killed two cops. Jose said it with such aplomb that the hardened inmates believed him, at least for a while.

Their old mentor at the orphanage, Patrick Atkinson, helped from the outside, hiring a lawyer, making frequent visits to the jail and endearing himself to the administration and the residents with gifts of soap, toothpaste and laundry detergent. Jose had become skilled at decorating plastic pens with embroidery, which the inmates produced for a dollar apiece. Atkinson boosted Jose's status by buying the trinkets in bulk, creating profits for the inmates. Jose and Martin got beds. After four months, Atkinson managed to get Jose freed.

But the young man kept faltering. He drifted from job to job and failed in his schoolwork. He slept at a youth shelter in Guatemala City and went from house to house on a bicycle, collecting bills for a cable TV company. He began sniffing glue and smoking pot and indulged his fondness for El Gallo, Guatemala's potent national beer.

Then in 1993, Veronica Morales, a social worker dedicated to recovering the true identities of street children, took up his cause. She told Jose that he must find his missing sister to regain his footing. So the orphan and the social worker began trekking through the alleys and enclaves of Guatemala City.

After a few weeks, they came upon the stall of the street vendor, Clotilde Lopez. She hadn't moved her business a foot in 10 years. She remembered the boy and his father, and this led them to a familiar market and then to the neighborhood where Jose and sister Engracia had parted ways.

Morales says she knocked on dozens of doors, asking, "Do you recall a girl who lived here once and was given away?" One family remembered a girl who now worked in the central market downtown.

They approached the market and, through the bustle, Morales recounts, Jose spotted a petite, dark-skinned woman selling avocados. He had a vision of his mother.

"Jose Antonio?" the girl asked.

"Chela," he said, crying out her childhood name.

He wanted to be a big success. He wanted to come back and see his old friends and show off his car, his new life. 'Here's my money.'

— Martin Calan

They embraced and tears fell down their cheeks. Jose informed Engracia that their father had died a decade earlier. They eventually moved in together, and Jose made a last stab at finishing high school.

But within three years he left his sister and Guatemala.

"He wanted to be a big success," says Calan, whose right arm still bears Jose's handiwork from their days in jail, a tattoo of a winged heart pierced by a sword. "He wanted to come back and see his old friends and show off his car, his new life. 'Here's my money.' He was so much smarter than me and the others, but he never seemed to able to dedicate himself to a single job or task. That's why he was always so attached to the idea of going to the north."

Jose's first attempt to get to the U.S. in 1994 ended after a disastrous two weeks in Mexico, in which he was robbed and his best friend had a nervous breakdown. On his second try, in fall 1996, Jose landed in a Mexican jail and pleaded with Atkinson to wire him $600 so he could get out. His mentor agreed -- on the condition that Jose return to Guatemala. Jose made the promise, and then headed for a different border.

From Los Angeles, he wrote Atkinson apologizing for the deception.

"I came to the U.S. to help my sister and those in need," he wrote. "God has helped me because only he knows how much I suffered in life to arrive where I am. It was very hard, but today I have the opportunity to move ahead and this time, yes, I will do it."

An L.A. Place but Not Peace

Jose Gutierrez stepped inside the small brown cottage in Pacoima in May 1997 and studied all the details of his first American home: the woven rugs laid out like artwork on the hardwood floors; the plush couches and polished pieces of wooden furniture crammed into every corner; the bookcases and cupboards illuminated with tiny bulbs that showcased porcelain dolls and framed photographs of the Castrellon family.

Vicenta Castrellon, the matriarch who filled the house with the aromas of her Mexican cooking, got right down to business.

What are your ambitions, she asked the skinny kid with the sickly cough.

Jose told her he wanted to go to school and become a famous architect. He wanted to make enough money to help his sister.

Vicenta and her husband, Jose, had raised four children, and a fifth was getting ready to leave. Their house had grown too quiet, so the couple opened the home to two orphans: Jose Antonio, a 22-year-old posing as a high school sophomore, and a 17-year-old bookworm from Mexico named David Gonzalez.

The young men shared a small room with two beds, a TV and a cassette player. Vicenta told them not to worry about the instruction packet that had come from the foster agency, with its long list of chores and rules. She had come up with her own philosophy for raising kids: Study hard and I'll take care of most everything else.

In the warm glow of the Castrellon house, the two orphans became friends. "We did everything together," Gonzalez says. Jose took him to nearby Ritchie Valens Park and taught him how to finesse a soccer ball down the field without giving up an inch. Gonzalez, an accomplished marathon runner, took Jose on early morning jogs.

At night, they played chess on an old warped board until Jose made a new one. He cut a piece of plywood, drew the squares one by one and painted them black and white.

Side by side, they headed off to San Fernando High, Gonzalez pedaling his rusty six-speed slowly enough so that Jose could keep up. Schoolwork didn't come easily for Jose. One day, he talked about quitting school and getting a job.

Vicenta Castrellon grabbed an orange from a basket of fruit and held it up. Each day is like this orange, she recalls telling him. You need to squeeze all the juice out of it. He could help his sister even more if he went to college.

Jose began to devote himself to his studies and became a top player on the school soccer team. He took English classes at night.

He would cook meals and play for hours with Vicenta's grandchildren in the most tender way. Your rosebushes need pruning, senora, he would tell her, heading outside with the shears. He cut a heart out of soft construction paper and made a birthday card for her in the form of a book. On the front cover, he drew and colored a perfect rose. He collected teddy bears -- brown, black and white -- that he boasted were gifts from the chicas, or girls. Sometimes, over a cup of coffee, he would let go of a story from his past.

By mid-1998, Jose's relationship with his roommate had begun to sour. He threw a dark bedspread over the windows and spent his free days watching TV. He played salsa music and watched reruns until 3 in the morning. The two young men argued constantly.

Gonzalez says he finally told the county social worker that one of them had to go.

A few weeks later, in February 1999, Gonzalez came home from school and noticed the teddy bears were gone. What he didn't know was that Jose had told the social worker he was concerned about Gonzalez's grades and had offered to move out.

Vicenta Castrellon says she felt a knot of misgiving as Jose left her house that day. He was carrying a large shoulder bag and a backpack full of his writings.

In a letter addressed to God he would later write: "Thank you for making me different from everyone. Only you accompany me, in the good and the bad. Only you know what I think of the world, and of each one of its people."

Fumbling a Second Chance

The phone rang inside Martha Espinosa's Gardena apartment in the spring of 1999. It was a friend from the Penny Lane Foster Agency.

I have a case for you, she recalls the friend telling her, but he's difficult.

Espinosa, an economist from Ecuador, had three grown daughters, the youngest still living at home. She had begun taking in foster children in the early 1990s and had earned a reputation for reining in the most troubled teenagers.

Espinosa sat Jose down that March afternoon and told him that only two rules governed her house: unconditional honesty and mutual respect. For days, they observed one another from the corners of their eyes, a kind of hushed wariness.

"He was street-smart, like a little cat, approaching, approaching but never letting his guard down," says the former banking executive. "He observed everything."

Jose spent long hours in his room, listening to Mexican rock music and writing poems. He was a deep thinker, and Espinosa thought she might reach him with books by giants of Latin American literature. She introduced him to Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Pablo Neruda.

In the evenings, over coffee, they sat down to discuss each book's themes in long conversations that took in history, geography and economics, as well as his past. He asked her questions for which she recalls having no answers. Why did God take away my parents? Why did I react the way I did?

He wanted to write a book about his life story, Espinosa says, and tell about the street children of Guatemala. He wanted to become a famous soccer player. "I told him, 'Soccer stars get famous quick, but what happens after they stop playing? No one ever forgets a man with a degree, a title.' "

She bought a big pink house in Gardena with a wide backyard that Jose landscaped in his bare feet. He spread seeds for grass and planted small pine and palm trees, all part of his determination, she says, to become the man of the house. He reprimanded the younger children for not picking up after themselves and gently scolded Espinosa for her habit of taking late night walks.

One night, she says, he pulled her aside and wondered if she might keep a secret. He wasn't 17, he told her with a grin. He was 24. He had lied to stay in America.

Espinosa kept his secret as he enrolled at North High in Torrance, joined the soccer team and earned a 2.9 GPA. Social workers found his grades remarkable for someone who was still learning English.

He was also memorable outside school.

He attended a Thanksgiving dance for Penny Lane foster children and dazzled everyone with his bold moves -- salsa, merengue. All eyes were on Jose as he spun around one of the directors and pulled her close to him.

"He was contagious," says Jose Zavala, a social worker. "All the women were looking at him, and you could see it in their eyes. They wanted him to ask them to dance. There was just this aura about him."

But privately he was far less secure. He would tell his foster parents and his caseworker that terrible things he had done in Guatemala still haunted him. He worried he had not escaped the grip of his past.

Most of the shrubs he planted in her yard, Espinosa later learned, had been stolen from other homes. Whenever a hankering for fruit overcame him, Jose would sneak over to a neighbor's tree and swipe a dozen big ones.

"I'm going to harvest," he would tell her on his way out to another picking.

She says she forgave all his minor transgressions, chalking them up to his rough upbringing. The short, erotic poem he wrote in the winter of 1999 was another matter, however. She knew right away that the object of his obsession was her 21-year-old daughter.

"I wanted to scream and say, 'No!' I asked him, 'Jose, is this a poem based on real feelings or is it from your imagination?' He said, 'Real feelings. I'm in love with your daughter.' " Espinosa warned him against acting on those feelings. She could lose her license.

A few weeks later, he was gone.

"Goodbye," he told Espinosa in a last note. "All that remains are the wilting roses, which were always for you. We say our goodbyes with our arms stretched toward each other, our friendship strong. But destiny pushes us in opposite directions, to realms uncertain."

A Fateful Decision

Days before he shipped out to the Middle East, Jose sat on Martha Espinosa's living room floor, painting a rose on white paper, then mounting the artwork as a gift.

After leaving Espinosa's house, he had been placed in two other foster homes, then moved into an apartment that was a transitional home for foster youths about to turn 21.

"He began to become depressed," says Marcelo Mosquera, his last foster father. "It entered his head that he would become alone."

Jose still spent time with the Mosqueras in their Lomita home and sent Engracia pictures of Marcelo's wife, whom he called "Mama Nora." He took special pleasure in caring for the younger foster children living with the couple, although in the past he had complained to his caseworker and former foster families about baby-sitting chores.

Members of the Mosquera family say Jose's depression began after he graduated from North High and enrolled at Harbor College. He started drinking more, and Marcelo Mosquera gave him a lecture, along with a job in the family's Hawthorne machine shop. But Jose later quit.

Throughout his life in Los Angeles, Jose had kept his sister informed about his life through photographs and Sunday phone calls. He sent her trinkets, including a plate painted with the Golden Gate Bridge and Santa Monica beach. His letters had been mostly upbeat; he would joke about his fictional family, writing Engracia in his neat, Catholic-school Spanish that his "wife and the little one are doing well."

But on March 10, 2002, his writing signaled a different mood: He missed her cooking, especially her tamales. He reminded her to take pity on those less fortunate. "When you see a street child whom you can help, help him, because that's where I would be." Then he wrote that he had given up on his architecture studies, which were "going very badly," and had lost his job.

With so much collapsing around him, he told her, he had come to a big decision: He was joining the Marine Corps. He told friends he was going to earn money and qualify for college scholarships. He would begin a three-month infantry training course in a few weeks.

"He looked for security and family wherever he could: in the orphanage, with foster families, in the Marines," says Veronica Morales, the social worker in Guatemala.

After joining up, Jose bonded with a group of Spanish-speaking Marines who competed over who could dance with the most women at local cumbia clubs around San Diego. As in their races to the top of a hill, Jose almost always won.

In letters to his sister and former foster parents, Jose detailed the rigors of being a Marine, of being punished with extra exercises for playing the clown and speaking out of turn, of having to ask permission to go to the bathroom. He was appalled at the five minutes that recruits were given to eat breakfast -- and that they could use only one hand.

But he also conveyed a sense of satisfaction.

"We are the best-known armed force in the world," he wrote to Engracia as he prepared to go overseas. "Just mentioning the word 'Marines' brings tranquillity, because people know it is safe."

He sent along a picture of himself, in uniform, the day he graduated from basic training. "Feel proud to have a brother who is very intelligent and very valiant, because from today on my life is no longer mine, it has entered the realm of mystery, because I don't know what's going to happen."

On Sept. 13, 2002, he was assigned as an infantry rifleman to the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment.

His letters home were alternately humorous and dark. He promised to send to Engracia a shark that he would catch while crossing the Pacific Ocean. Then he stressed that she should alert him "as soon as possible" if she changed her address, "because if something happens to me or I die, they will pay you instead of me."

Bad News Gets Worse

The knock on the door came sometime after midnight. Two men from the U.S. Embassy, accompanied by a contingent of Guatemalan police, asked if she was the Engracia listed on the form of a U.S. Marine named Jose Gutierrez. She thought it might be a mistake. There was no "Antonio" as the middle name.

They told her an enemy bullet killed him. The spokesman for the Central Command in Qatar said the same thing. It would be weeks before Engracia learned the truth. Jose, it turned out, had been killed by friendly fire, said a March 29 letter from Col. T.D. Waldhauser, commanding officer of the 15th Marine Expeditionary Force.

The details remain sketchy. Jose's unit, the colonel wrote, had just finished clearing a building when he was shot. Jose was "a true warrior for a righteous cause," wrote the colonel in his letter of condolence.

"I still can't believe he was killed by one of his fellow soldiers," says Engracia. "I just find that hard to accept. I know it won't bring my brother back to life, but I want to know what happened to him."

Jose's funeral in Guatemala City was a gaudy affair, with hundreds of onlookers. A light drizzle was broken by bright sunshine. Green canvas tents were erected for the international press and the diplomatic corps. Tiny Guatemalan and U.S. flags were planted on the grounds.

None of his friends from the orphanage were invited. Jose had been given the plot of a rich man. The stainless steel casket sat near the fountain at the entrance of the cemetery named after the cypress trees that graced its path. The U.S. government was picking up the tab. As a beneficiary, Engracia stood to receive $250,000 -- an unimaginable sum for a Guatemalan fruit vendor.

On the Saturday before Easter, she returned to the cemetery with Patrick Atkinson from the orphanage, and Veronica Morales, the social worker who had reunited brother and sister a decade earlier. They exchanged letters, photos and stories of Jose.

To the grave, Engracia took pink roses and soil from the rich black volcanic earth of the mountain that was their father's ancestral home.

When she dies, she wants to be buried beside Jose Antonio, with the remains of her mother and father and baby sister -- now scattered in unmarked graves across the city -- all in one plot.

"That way we would all be back together again," she says. "That is my dream."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.