The epic and ugly battle over what to do about the 710 Freeway

- Share via

Few Southern California transportation projects have a longer or more tortured legacy than the 710 Freeway.

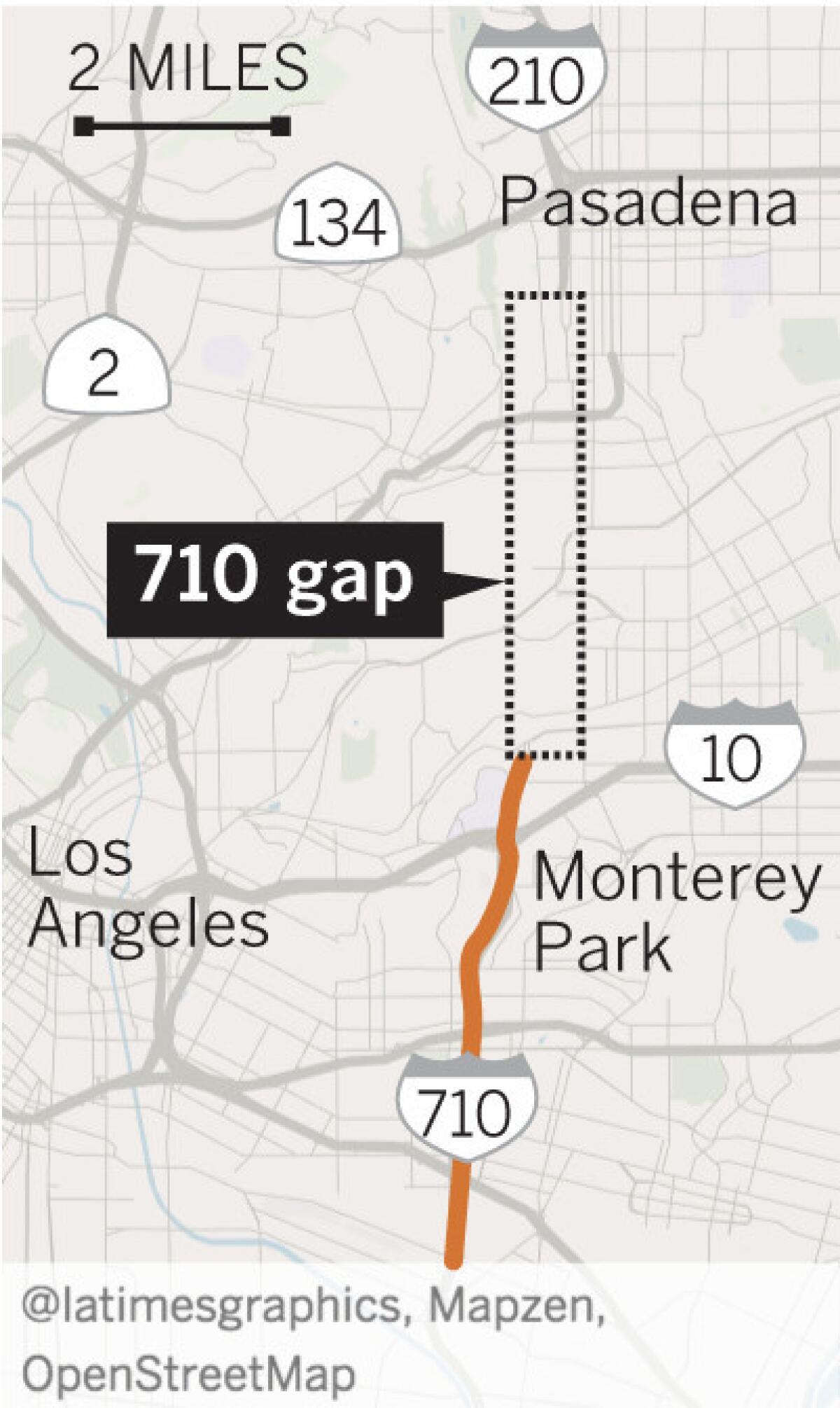

Since the 1960s, the debate over whether to close a 4.5-mile gap in Los Angeles County’s freeway network has raged between preservation advocates in South Pasadena and cities in the San Gabriel Valley, where the 710’s abrupt terminus sends freight traffic spilling onto local streets.

Update: Metro board of directors withdraws its support for controversial 710 Freeway tunnel »

The sparring began again last week, when a Metropolitan Transportation Authority staff report endorsed a 4.9-mile, $3.2-billion freeway tunnel as the most effective way to connect the 710 and the 210 Freeway.

The tunnel, which would be the longest of its kind in California, may effectively meet its end Thursday, when Metro’s directors will consider shifting hundreds of millions of dollars in 710 project funding toward local street improvements.

The plan, if approved, amounts to an unofficial decision on the future of the 710 corridor. Without an estimated $700-million contribution from Metro, the chances of Caltrans funding and building a multibillion-dollar freeway tunnel are slim to none, officials say.

“Realistically, I don’t see the tunnel coming back,” said Metro Chairman and Duarte Councilman John Fasana, who introduced the proposal with L.A. County Supervisor Kathryn Barger. “That’s not to say that someone can’t come up with another idea 20 years from now. But this funding will be gone.”

Another Metro official, who was not authorized to speak publicly, described the tunnel’s future as a “fait accompli.”

Fasana, a longtime supporter of the 710 extension, said his proposal was a response to Metro’s staff report supporting the tunnel. He noted that the project has scant political support on the Metro board and a funding gap of more than $2.5 billion.

“I support the tunnel, but after all these years of delivering no improvements, we owe it to these areas to pursue a different path,” Fasana said. “It makes sense to step away from our pursuit of this and see if there are other solutions.”

The 710 corridor has about $780 million in funding guaranteed through Measure R, the half-cent sales tax increase voters approved in 2008. Some of those funds have already been spent on environmental reviews and other studies.

Fasana’s proposal would allocate $105 million of the remaining funds toward synchronized traffic lights, new meters on freeway off-ramps and capacity enhancements at three dozen intersections and local streets, as well as incentives to encourage carpooling, transit use and staggered work schedules.

The remaining budget would be dedicated to “new mobility improvements” in the San Gabriel Valley, according to the motion.

The option was among the possibilities included in the project’s environmental review.

Fasana’s proposal is a blow to San Gabriel Valley officials and advocates who have complained for decades that the freeway’s abrupt ending on Valley Boulevard causes health and air problems.

The 710 is a favored route for truckers shuttling between the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and distribution centers in central Los Angeles County.

Alhambra Mayor David Mejia said the city will weigh its options, including litigation, after Metro votes Thursday, saying: “The tunnel is the best thing for our city. We want our problems to be taken seriously.”

The other options under consideration for the 710 corridor are a light-rail line, a bus rapid-transit route or a variety of tunnel options, including single-bore and twin-bore tunnels.

The so-called traffic demand management plan backed by Fasana and Barger received a lower rating overall than the tunnel options, according to the Metro staff report. Local road upgrades would do little to address congestion on surface streets and would have about the same effect as a tunnel on regional freeway traffic, the report said.

In advance of Thursday’s vote, here’s a look back at the long, convoluted history of the 710 corridor.

1930s and 1940s

The first tentative 710 routes are born

As state transportation officials began to map out California’s vast future freeway network in the 1930s, they included a connection from Monterey Park to Long Beach, dubbed “Legislative Route 167.”

In 1949, then-Gov. Earl Warren signed legislation extending the route farther north into South Pasadena.

1950s and 1960s

Work on the freeway begins

In 1951, crews began working on the southern portion of the 710, which connects to the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles.

In 1964, the California Highway Commission adopted the so-called Meridian Route, named because it parallels South Pasadena’s Meridian Avenue.

Caltrans began purchasing homes along the expected route of the freeway in El Sereno, South Pasadena and Pasadena.

1965

The freeway is finished — kind of

Caltrans opened the freeway in phases and cut the ribbon in 1965 on a 1.3-mile segment from the 10 Freeway to the 710’s current terminus on Valley Boulevard in Alhambra. Protests from South Pasadena over the planned northern route delayed further construction.

1973

The lawsuits begin

Three years after California and federal officials approved sweeping environmental legislation, the city of South Pasadena, the Sierra Club and other organizations sued in federal court, saying the 710 project should be subjected to a more rigorous environmental review.

A judge issued an injunction halting construction until the studies could be completed, which effectively blocked the freeway for 25 years.

South Pasadena later amended its general plan to show public buildings in the path of the proposed freeway, prompting a lawsuit from Caltrans.

1977

What if we made it smaller?

The state’s final environmental documents recommended a scaled-down version of the freeway, with four lanes. Federal officials balked, and work ground to a halt.

1980s

Cutting out cities’ consent

In 1982, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill that allowed Caltrans to build the freeway without the consent of municipal governments such as South Pasadena. But it required more environmental studies, and a decision on a route, by 1985.

Two years later, state officials approved a route they had previously endorsed, along Meridian Avenue. They also rejected a series of suggestions — including a possible double-decking of the 110 Freeway — made by a federal advisory group on historic preservation.

1992

Governor to Caltrans: Build it already

Gov. Pete Wilson’s administration ordered the freeway built, and federal highway officials issued a long-awaited approval for the environmental study.

1995

Lawsuits start up again

In 1995, El Sereno activists filed a federal race discrimination lawsuit against the state, alleging that the route through their largely Latino neighborhood lacked the noise mitigation promised to Pasadena and South Pasadena.

April 1998

Federal government approves the 710 extension

Late on a Monday night, officials with the Federal Highway Administration signed the so-called record of decision approving the 6-mile freeway extension.

It was a blow for freeway foes, who had hoped the federal government would stop the project. Still, the groups won a last-minute concession that officials would review the project again after it was fully designed.

Later that year, South Pasadena sued again in federal court, saying the document failed to protect the environment and historic homes and businesses.

1999

Judge blocks freeway construction

In a major victory for South Pasadena, U.S. District Judge Dean Pregerson ruled that Caltrans and federal officials may have violated the Clean Air Act and failed to consider alternatives for the 6.2-mile freeway project.

Pregerson said the agencies had not prepared adequate environmental impact reports and had not adequately considered so-called low-build alternatives to help traffic flow on surface streets.

He blocked the agencies from spending money on construction or acquisition of properties along the proposed freeway’s path.

2000

Pasadena changes course

After decades of supporting the project, the Pasadena City Council rescinded its support of the 710 and joined South Pasadena in opposing the project.

In an hours-long and sometimes-heated public hearing, the mayor of Monrovia told City Council members that reversing course would only prove that “you just care about your own parochial needs.”

2003

Federal officials back away from freeway plan

Federal Highway Administration officials rescinded their approval of the 710 project, telling Caltrans officials that so much time had passed since the environmental review in 1992 that it would have to be redone.

Since the project was first studied, 11 additional historical sites were identified in the freeway project area, the Gold Line opened to Pasadena and the Alameda Corridor freight train route opened, which could relieve some pressure from the 710, officials wrote.

Can a $5.4-billion tunnel plan fix the notorious 710 gap? »

2008

New sales tax funding renews the 710 debate

Measure R, the half-cent sales tax increase that voters approved in 2008, included $780 million to study possible improvements along the 710 corridor.

South Pasadena and La Cañada Flintridge filed a lawsuit over the Measure R ordinance, saying Metro was improperly funding a project that had not undergone a full environmental review. The lawsuit was later thrown out.

In 2009, Caltrans began exploratory drilling for an environmental study.

March 2015

A new freeway price tag: $5.6 billion

A 2,260-page draft environmental report prepared by Metro and Caltrans examined four options for closing the 6.2-mile gap between Alhambra and Pasadena.

Building an underground freeway would be the most expensive option, at $3.1 billion to $5.6 billion for single- or twin-bore tunnels, and would take about five years to complete, the report found.

Metro and Caltrans said they would consider a bus system, a light rail line and various upgrades to the existing route, as well as a “no build” option.

2015

Caltrans starts preparing to sell some homes in the path of the 710

With all surface freeway options off the table, Caltrans began preparing to sell more than 400 homes purchased in the 1950s and ’60s in preparation for freeway construction.

May 2017

Tunnel may be scrapped

Last week, Fasana proposed that Metro dedicate the remaining Measure R funds to improvements to traffic signals, streets, intersections and bus service. Officials could also encourage residents to reduce solo car trips in the area surrounding the 710 gap, between Alhambra and Pasadena.

The final decision rests with Caltrans, which is expected to vote on an option later this year or in 2018.

Update: Metro board of directors withdraws its support for controversial 710 Freeway tunnel »

Twitter: @laura_nelson

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.