Column: In teachers’ strike settlement, public support for education was the best news

- Share via

Ring the bell, load the backpacks and start the buses.

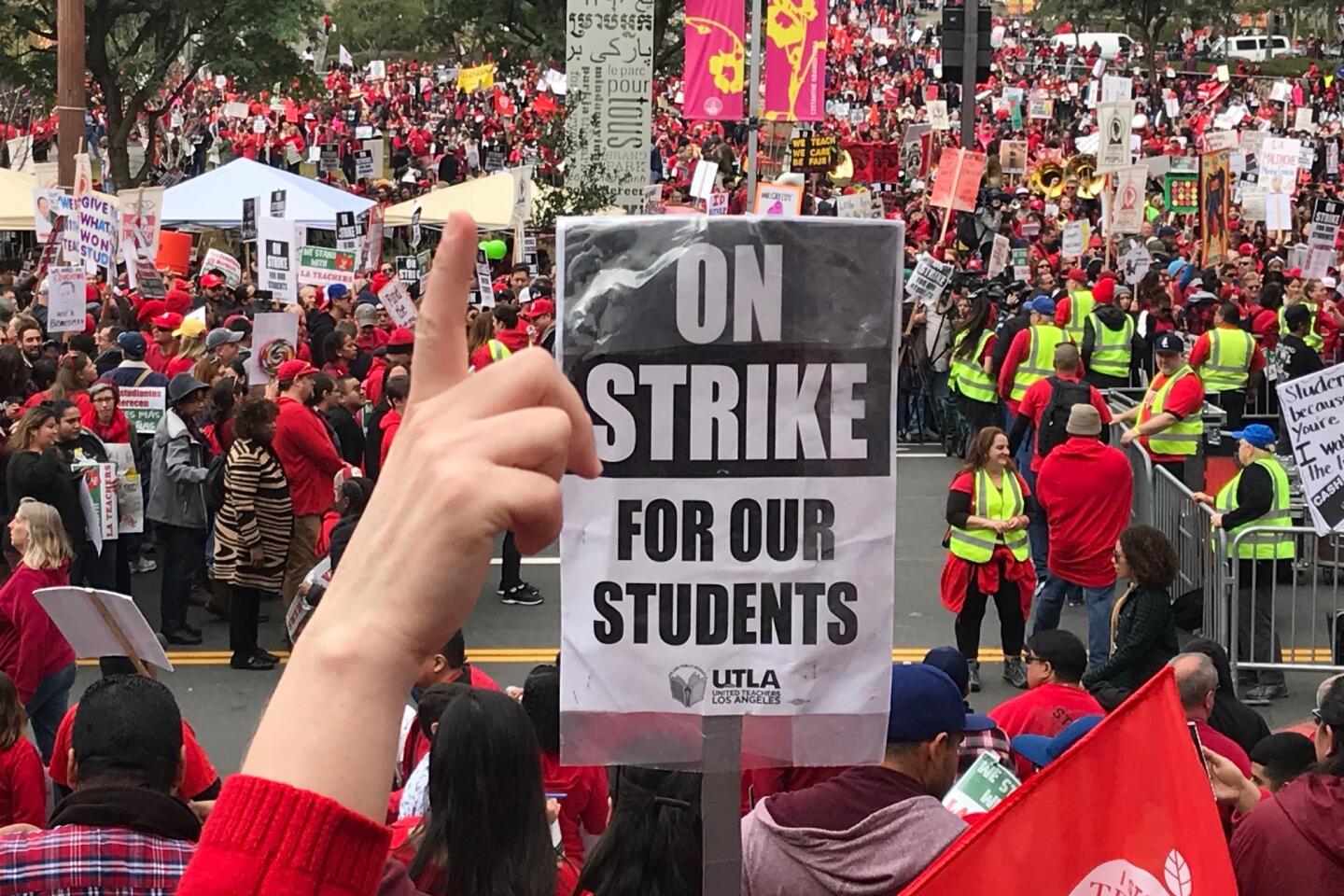

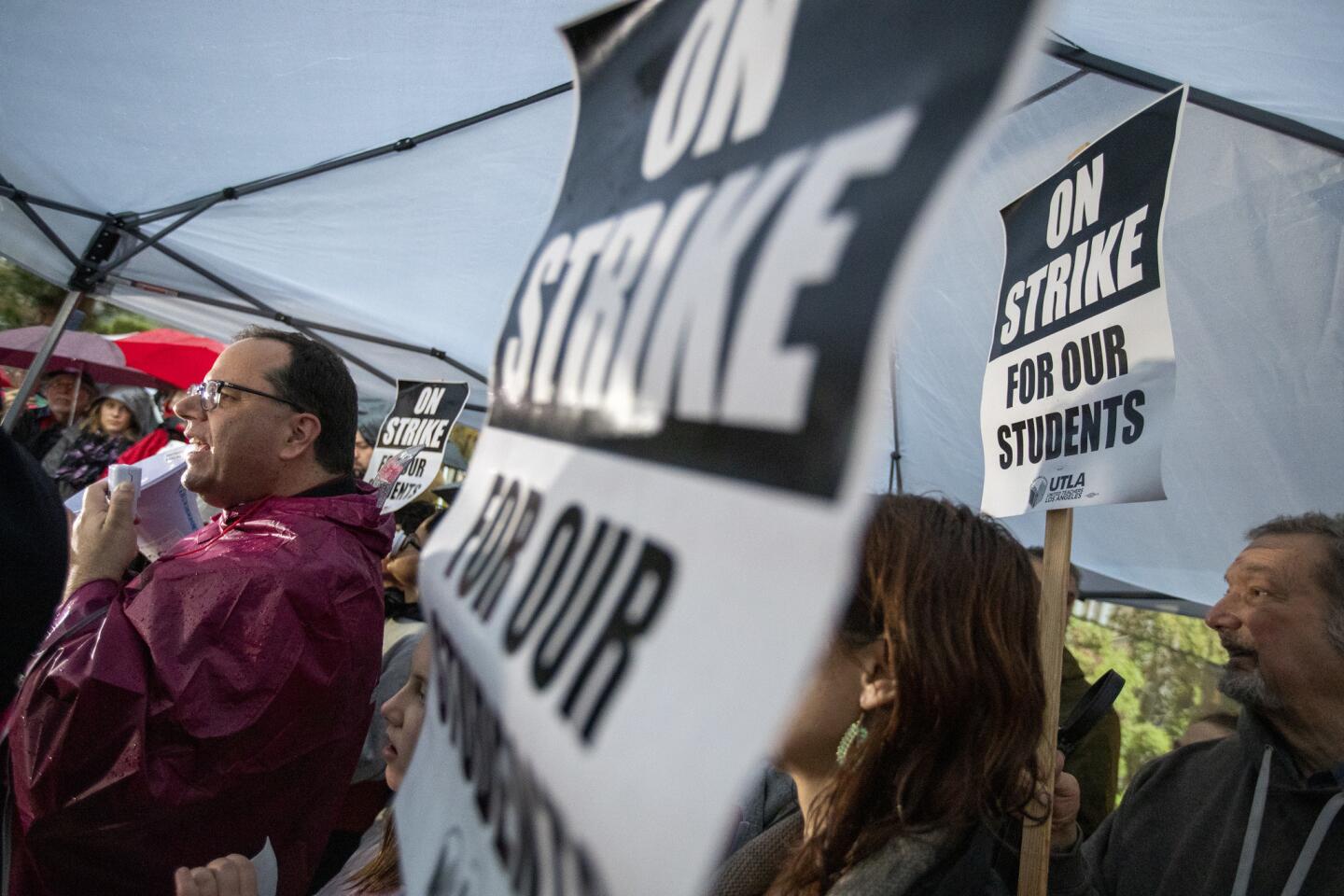

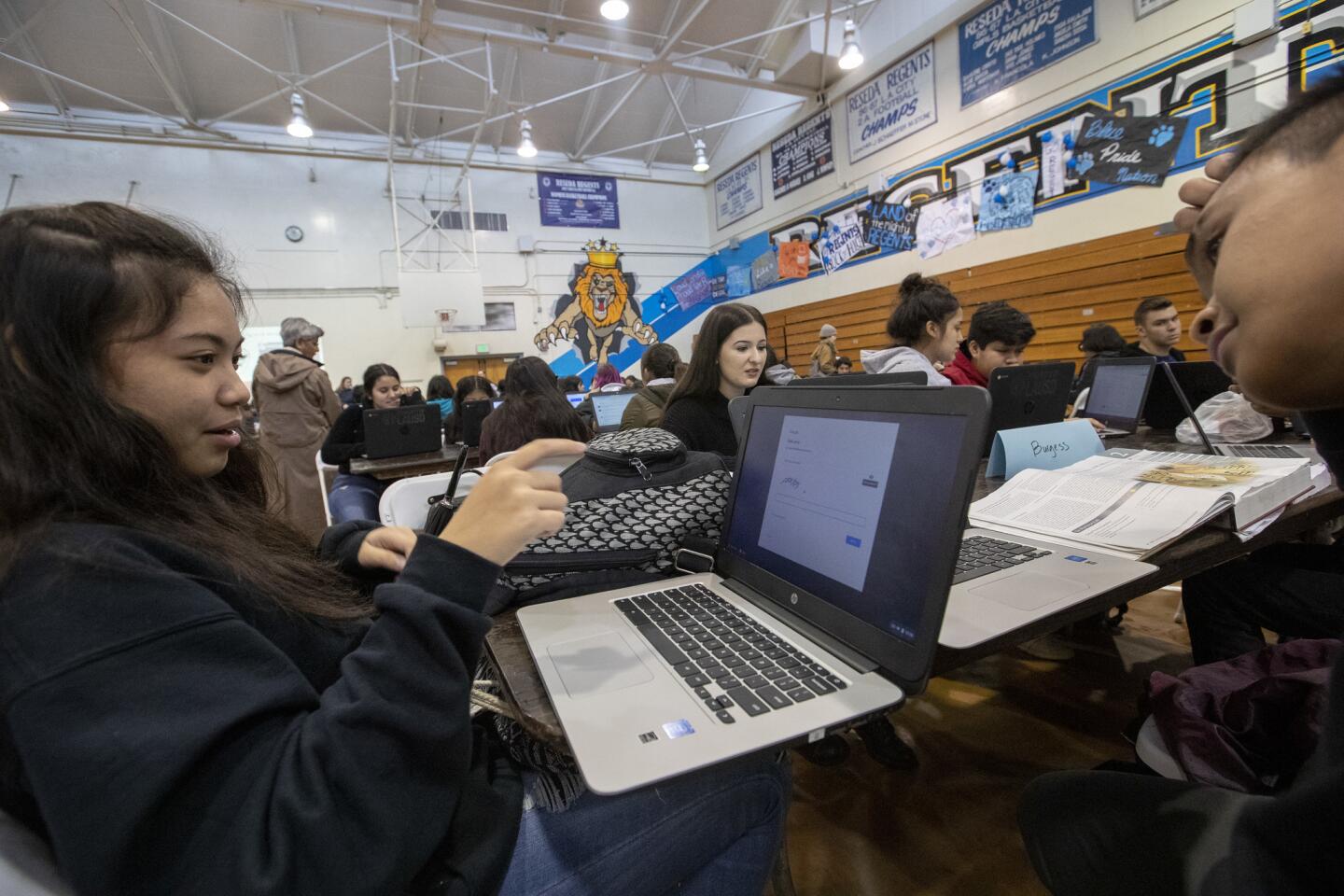

School is back in session in L.A. Unified, with teachers returning to work on Wednesday after a six-day strike, the first one in 30 years.

That’s good news in just about every way.

For teachers, staff, students and parents.

Did the union win? On some stuff, not everything.

Did the district win? Same answer. It gave a bit, though it mostly held firm on its claim of poverty.

Not to rain on the parade, but I do have a question: Why the heck did it take 20 months and a six-day strike to negotiate this contract?

That can only be seen as a failure of leadership, all around, and not just by the district and the union. There was no sign of our ace city and county officials until the tail end, when someone must have sent out a search party for L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti and he hosted the final days of contract negotiations at City Hall.

On pay, class size and support staff, including nurses, librarians and counselors, what the union settled for was not significantly better than what the district had offered before the strike began — a strike that cost teachers about 3% of their salaries for missed days.

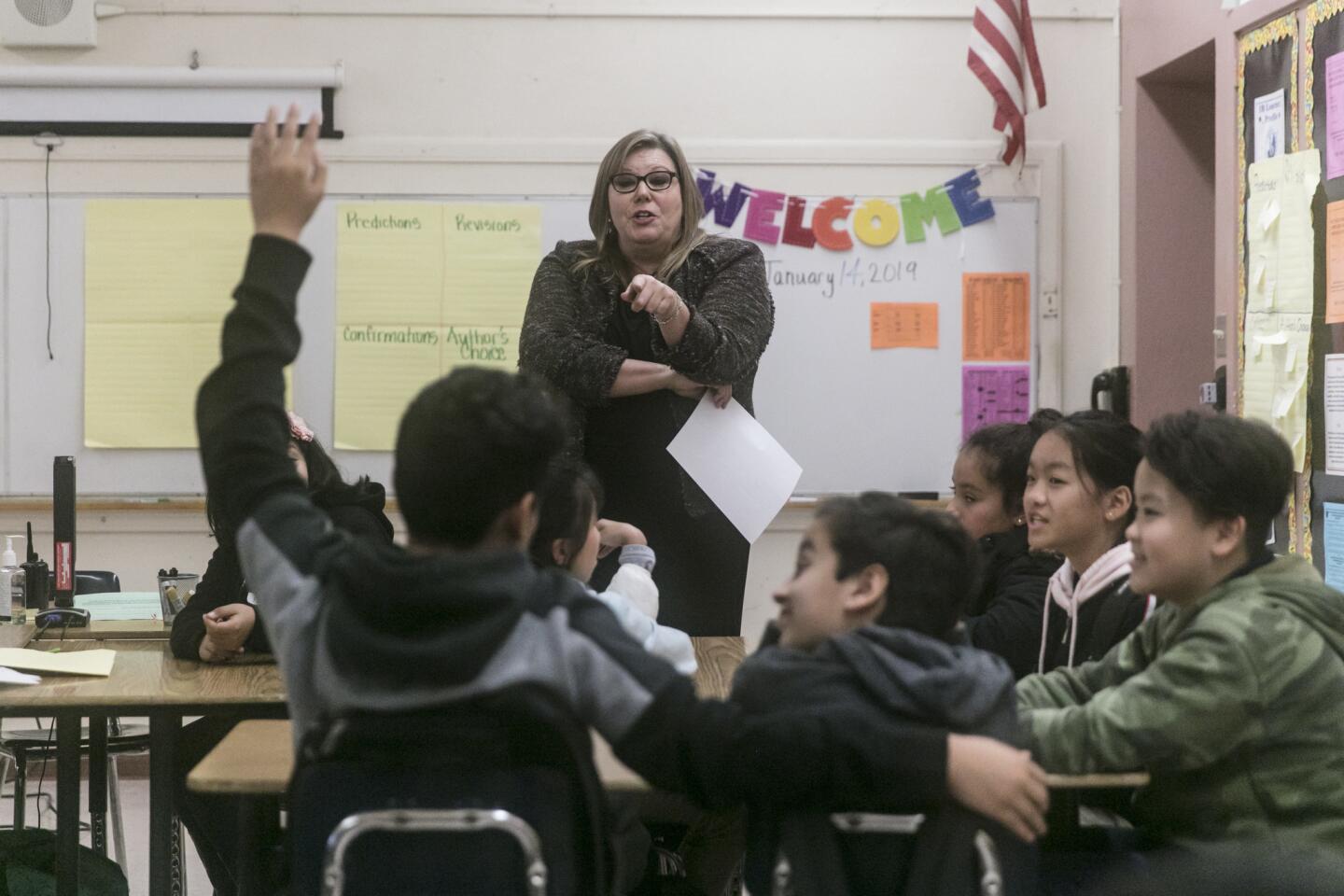

It was hard not to root for teachers on their demand for smaller class size, and they did make modest progress. But it’s going to take several years to scale up to a reduction of just four students, and that’s too long a wait for too small a change.

The union had wanted a moratorium on new charter schools, arguing that their growth has further depleted funding for traditional schools. But that was a philosophical rather than a practical demand, because charter law is a state matter rather than a local one.

Still, the union did score a commitment from the school board to vote on a resolution asking the state to establish a charter school cap. The board has a majority of charter backers at the moment, so I’m guessing the union calculated that it might take back school board control in the next election.

The union also got an agreement for the creation of 20 community schools, which provide wraparound services for students and their families. And that’s potentially a very good thing.

But the best thing about the strike, hands down, was the way it galvanized a usually disengaged public. I didn’t see that coming, to be honest, so I had it wrong and union leader Alex Caputo-Pearl called it right.

I thought teachers deserved what they were asking for and more, but I didn’t see the financially struggling district, with its rapidly declining enrollment, as the right target.

I feared that teachers, the district and students might all lose in a strike, and that the adults should have been able to forge a deal and together demand more support from Sacramento, which they are now pledging to do.

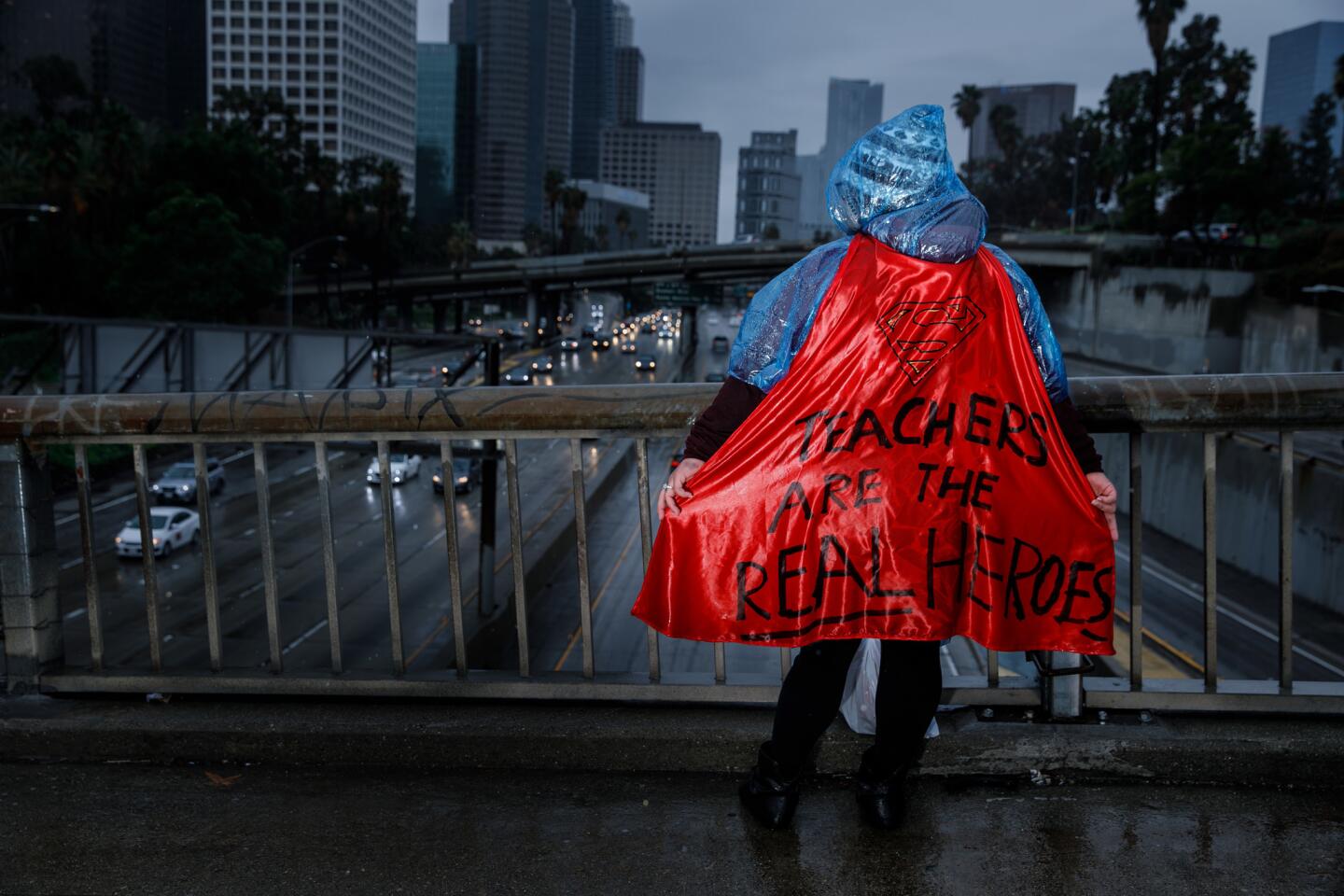

But for days, teachers marched in the rain, beat drums and dominated the news. After years of feeling beaten up and fed up, they saw drivers honking in support, parents joining the marches, and taco trucks showing up to feed them. And through it all, the spotlight was on the ways we’ve let public school students down in a staggeringly rich state that once sat proudly in the upper ranks of funding per pupil.

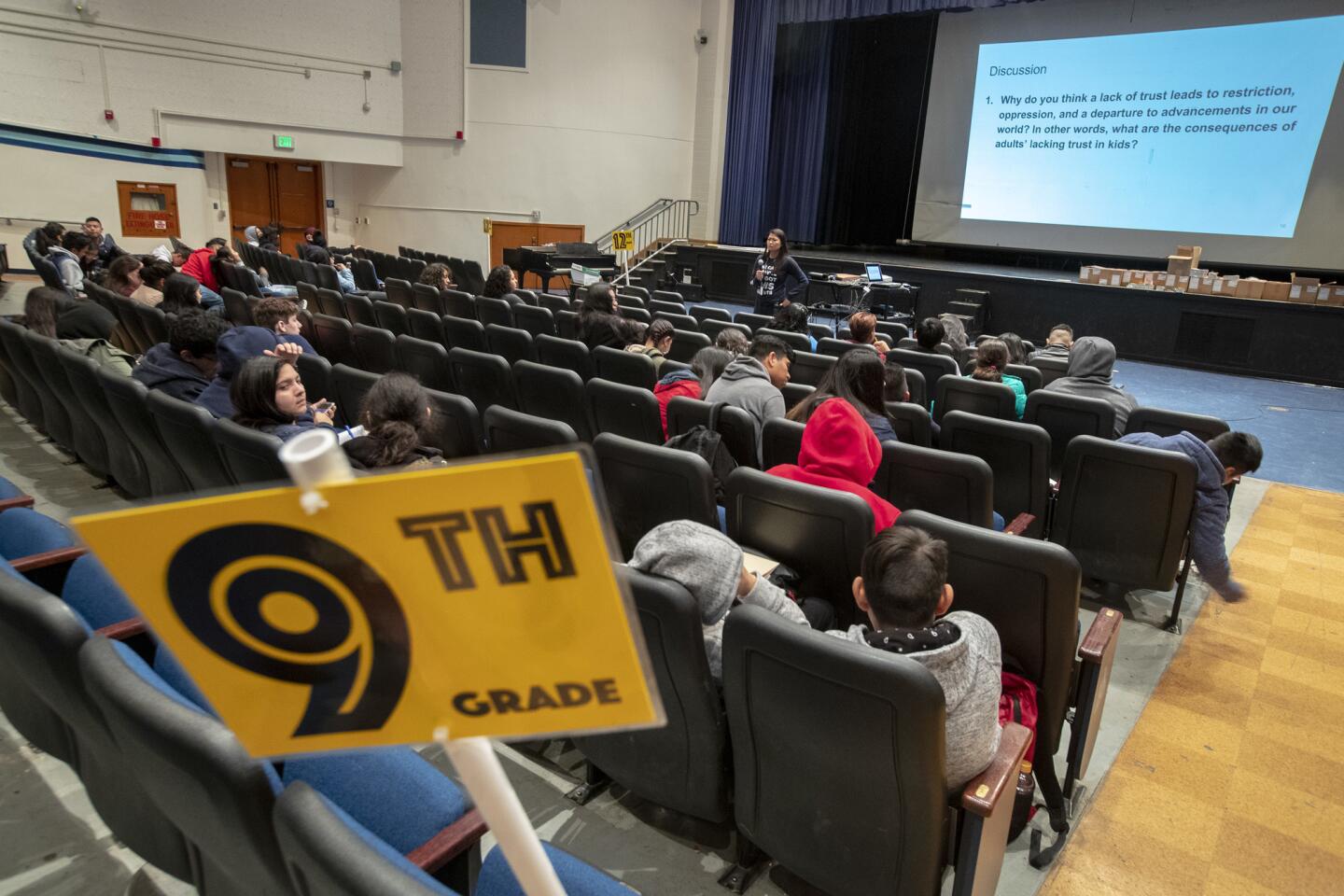

“Classes are so big, it can be really hard to learn,” high school student Ezra Bitterman said Tuesday morning on the picket line outside the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies, one of the district’s best schools. “My AP world history class has 40 students.”

That’s insane. And do not write to tell me, as many of you do, that you had 50 students in a class when you grew up and everything was fine. Student skill levels cover a wide span today, and having to do more testing than teaching doesn’t help anyone.

It was a family affair on the picket line, with Ezra’s sister Annabelle — a former LACES student — joining him. Also there was their mother, Cindy, a school district nurse who floats between four schools each week. Which is also insane.

Ezra said his teachers often purchase school supplies, and the school didn’t get a much needed paint job for years. It finally did but only because a reality TV show wanted to film there.

“This isn’t a contract negotiation,” Ezra’s playwright father, Shem, wrote to me. “It’s a historic battle for the right to a public education — with high quality, credentialed teachers, nurses, coaches, special service providers and the like…. This is an existential battle about democracy.”

OK, but let’s think even grander.

Why not housing subsidies for teachers and a single-payer healthcare system that cuts out corporate profit and helps pay for them?

Why not free public transit for all students and teachers?

As enrollment dwindles in the state, why not convert unneeded schools into workforce housing for teachers and staff?

We have a new governor who talks as if he wants to change the world, and while we want him to be fiscally responsible, he’s got a budget surplus bigger than the gross national product of most countries.

If the existential battle for democracy is to be won, we need to look past the schoolyard and the contract negotiating rooms and consider the big picture.

In places where students live in stable middle- and upper-income areas, schools do well.

Where students live in poverty, as 80% of L.A. Unified’s students do, schools inherit crushing burdens that can’t all be overcome.

What I learned in several weeks at the L.A. Unified school with the most homeless students, a school that once sat in the center of San Fernando Valley industrial prosperity, was that schools aren’t failing us; we’re failing them.

In California, busing, white flight and Proposition 13 teamed up to clobber public schools, and we didn’t do much about it. Then came the death of manufacturing, replaced by a service economy that drove more families into poverty, with wages falling and housing costs soaring.

Until somebody smart can invent an economy that works for more people, a full investment in schools is the least we can do.

I know this is a rare kumbaya moment for L.A. of hand-holding among long-feuding parties. But we all know that won’t last forever, and little will have been gained if this strike was the end of a conversation rather than the beginning of a campaign.

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.