For law enforcement, there is no single profile of a self-radicalized jihadist

- Share via

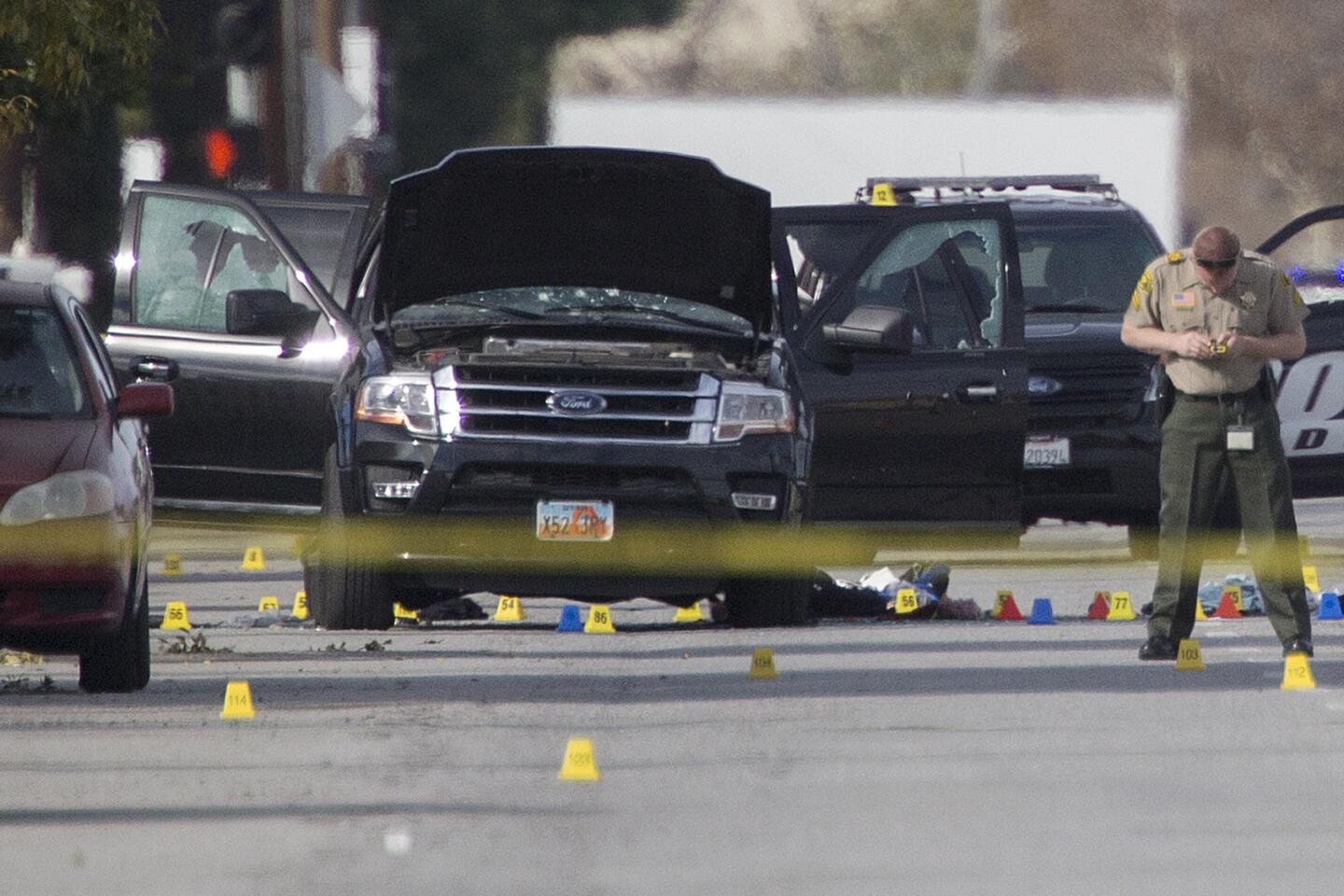

One question has persisted in the months since the San Bernardino terrorist attack: Could authorities have foiled the shooters’ plot before they opened fire?

Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife, officials said, were self-radicalized terrorists who built bombs in their suburban garage in the months before they killed 14 people at a holiday party.

Some in Congress have said the case underscores the need for the public to be vigilant in reporting suspicious activities — and not be overly concerned about singling out people who happen to be Muslim.

But coming up with a way to identify self-radicalized jihadists has proven difficult for law enforcement, despite massive efforts since Sept. 11, 2001.

There is no single set of characteristics to identify who will cross the line into violence. Attempts to create criminal profiles, similar to those used to track down serial killers, have generated fierce criticism for casting too wide a net.

Some homegrown jihadists have been well-educated with good jobs. Others whiled away hours playing video games and smoking pot. Some came from Muslim immigrant families, while others were converts to the religion.

Outwardly, Farook led a conventional life that did not arouse any suspicion. The San Bernardino County health inspector was known as well-mannered and devoutly religious. He was recently married and had a baby daughter.

The New York Police Department’s attempt to meld the diverse traits of American jihadists into a unified profile has been criticized for placing just about every young Muslim male under a cloud of suspicion.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

The department agreed to take its controversial report off its website as part of a settlement with the ACLU and others announced this year.

“You don’t need any common background to identify with something,” said Marc Sageman, a forensic psychiatrist and former CIA officer who has been critical of attempts to generate a profile. “You can have rich people, like Bin Laden, or poor people, like the guys [who attacked] in Paris.”

In the Los Angeles area, counter-terrorism leaders say they zero in on suspicious behavior rather than demographic profiles.

The Los Angeles Police Department tries to identify potential attackers with a “suspicious activity” checklist that includes trespassing, using false identification, taking photos of protected sites and accumulating large quantities of chemicals.

“Is it illegal to be a Muslim with a camera? Of course not,” said Deputy Chief Michael Downing, who oversees the LAPD’s counter-terrorism bureau. “If you can articulate what he’s doing, taking pictures with a nexus to a security interest, that might be something.”

Chief Scott Edson, head of counter-terrorism at the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, said his investigators rely on tips to pinpoint possible suspects who have recently undergone a drastic change. The signs might include casting old friends aside or expressing dissatisfaction with life.

“We depend on family and friends and community members to really recognize that some aspect of this person is acting different and give us that lead,” Edson said.

::

After 9/11, police officials in New York City stepped up their counter-terrorism efforts against overseas plotters as well as the increasing threat of homegrown jihadists.

In a 2007 report posted on its website, the NYPD described how “unremarkable” individuals with ordinary jobs and ordinary lives could evolve into people who slaughter innocent civilians.

Middle-class males 15 to 35 years old who spend time in Muslim enclaves were the most likely candidates for radicalization, said the report, which drew from nearly a dozen cases to reach its conclusions.

Beyond that, the descriptions ran the gamut, from “the bored and/or frustrated, successful college students, the unemployed, the second and third generation” to “new immigrants, petty criminals and prison parolees.”

Of this broad group, a few will experience a personal crisis, such as losing a job or family member, that draws them to extremist religion and eventually to violence, the report said.

The FBI released a report around the same time that similarly traced a path from pre-radicalization to embracing the cause to bonding with a group of like-minded jihadists.

Critics say such portraits are over-inclusive and provide a false justification for ethnic profiling and intrusive surveillance.

Ramzi Kassem, a law professor at City University of New York, said he believed the NYPD’s report functioned as a “blueprint of sorts” for the agency’s now-shuttered program that monitored mosques, ethnic restaurants and predominantly Muslim neighborhoods. Kassem represented plaintiffs in one of two lawsuits alleging that the department engaged in discriminatory surveillance of Muslims.

In addition to removing the report from its website, the NYPD agreed to prohibit investigations based largely on race, religion or ethnicity and to limit the use of undercover officers and confidential informants.

Lawrence Byrne, the NYPD’s deputy commissioner for legal matters, said the report was never meant to be a basis for police work. It was valid at the time but predated the rise of Islamic State, he said.

Faiza Patel, co-director of the Liberty and National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice, said such profiles are based on stereotypes and damage police relationships with Muslim communities.

“Rather than place a dragnet around an entire community, you focus on where you have suspicion of wrongdoing,” she said. “It shouldn’t be that being an observant Muslim is enough to trigger the Police Department’s scrutiny.”

::

Still, some terrorism experts believe there are clues that can help identify those who may turn to violence at a time when Islamic State is calling on its supporters to carry out attacks on their own initiative.

Efforts to develop a jihadist profile are valuable, they say, and should not be abandoned because of concerns about how the information is used.

One common thread may lie in aspiring jihadists’ deepest motivations.

People who a few generations ago might have joined violent domestic fringe groups like the Symbionese Liberation Army are now attracted to jihad, said Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at Cal State San Bernardino.

Levin has interviewed members of extremist groups with disparate ideologies, such as the Jewish Defense League and Islamists in the Middle East. He said he found consistent themes, including the severing of family ties and a desire to make a difference in the world by righting perceived injustices.

Brian Michael Jenkins, a national security expert at Rand Corp., was quoted as an outside voice in the 2007 NYPD report, endorsing it for the guidance it would provide to law enforcement.

Since then, Jenkins said, the terrorist threat to the U.S. has changed, with the danger more likely to come from small groups or lone wolves acting on their own rather than a large team of centrally controlled attackers. Jenkins said Islamic State’s graphic videos appeal to troubled individuals with a propensity toward a particularly gruesome brand of violence.

“The display of beheadings, crucifixions, mass executions — that has attracted a unique self-selecting group,” he said.

::

The three people linked to the San Bernardino attack illustrate just how different self-radicalized jihadists can be.

Farook, born in the U.S. to Pakistani immigrants, was seen by co-workers as “living the American Dream.” His wife, Tashfeen Malik, had earned top grades as a pharmacology student in Pakistan. She was known as a “modern girl,” according to relatives, until she began wearing a veil and attending a conservative religious academy. The two met on an online dating site.

Enrique Marquez Jr., who is accused of supplying two rifles used in the Dec. 2 attack on the Inland Regional Center, was a California native who worked as a security guard at a local Wal-Mart. Marquez did not appear to know about the plot, but prosecutors allege that he gave the rifles to Farook several years ago when the two men were planning attacks against Riverside City College and commuters on the 91 Freeway.

Farook, prosecutors say, introduced Marquez to jihad while they were next-door neighbors, first bringing him to a local mosque, then exposing him to the teachings of radical Islamic clerics.

Such bonds between aspiring jihadists can be more telling than individual biographies, said Robert Pape, a professor at the University of Chicago who analyzed suicide terrorists across three decades in his book “Cutting the Fuse.”

Odd social groupings sometimes form, as people who otherwise have little common ground meet at mosques, gyms or cafes and find they share the same obsession with jihad, Pape said. They eventually cut themselves off from previous relationships and hole up with their terrorist cellmates.

These types of plots are difficult to disrupt, because little, if any, of the planning gets beyond the inner circle. Farook remained in contact with his family, but investigators have identified only his wife as being involved with him in the plot.

“When the FBI and others are trying to catch them, they’re surveilling, listening to phone calls, tracking computer records.... But [would-be terrorists] are talking to each other face to face, watching videos together face to face,” Pape said. “Radicalizing in teeny tiny cliques of people is really difficult to find by surveillance.”

Twitter: @cindychangLA

Twitter: @vicjkim

ALSO

First-responders, investigators in San Bernardino terror attack honored

After San Bernardino attack, third shooter claims are just ‘human nature’

For San Bernardino shooting victim, the hardest part of recovery is fully conveying her gratitude

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.