Silver Lake pedestrian tunnel is set for closure, but some want it saved

- Share via

Urine soaked the floor. The walls got pasted over with pornography. Vagrants cut through the gates that had been meant to keep it sealed and hauled in bedding and cabinets — a “Mouse House,” as someone scribbled in spray paint across the wall.

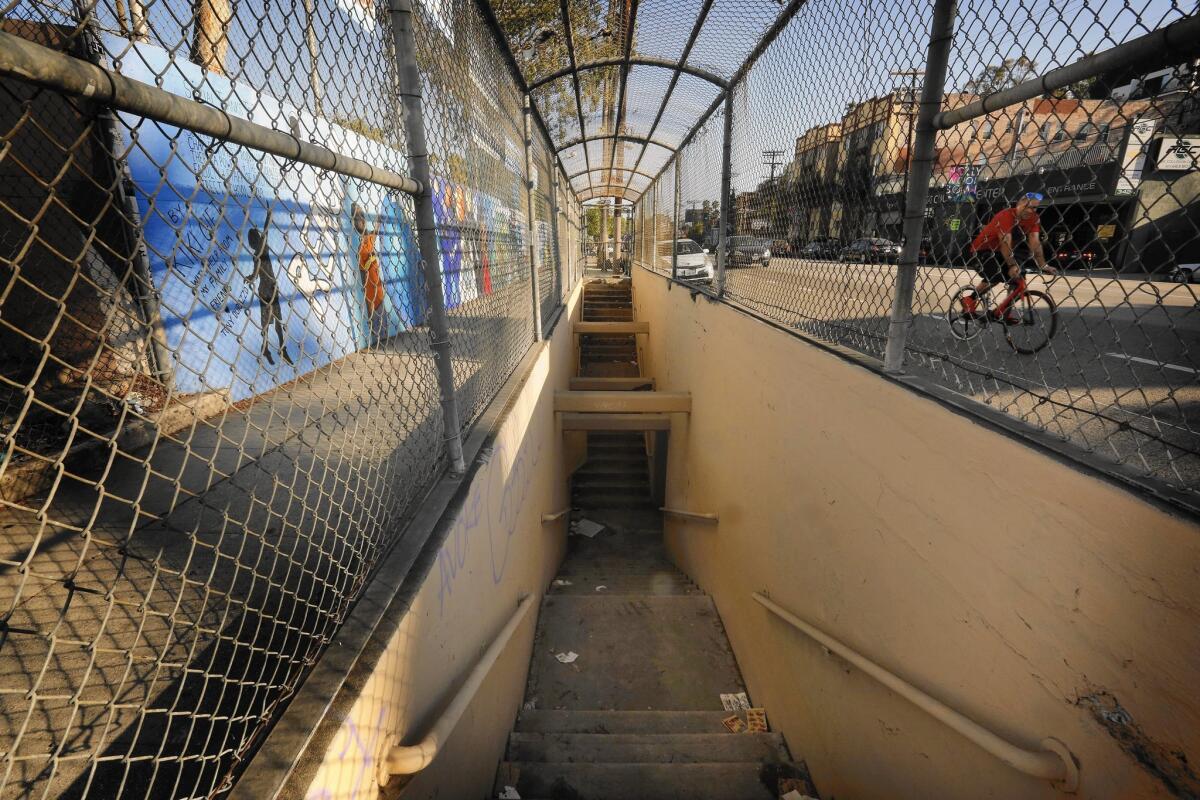

The pedestrian tunnel — 75 feet long and 8 feet wide — burrows from Micheltorena Elementary School to the other side of Sunset Boulevard in Silver Lake.

It is one of the 221 built in the 1920s and 1930s with more than $1 million from bond issues approved by Los Angeles voters after the Evening Herald newspaper led a tunnel-building campaign to “save the lives of children.”

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Pedestrian tunnels: In the Sept. 3 California section, an article about Los Angeles’ plans to close a pedestrian tunnel in Silver Lake included incorrect information. There were not 221 pedestrian tunnels built in Los Angeles in the 1920s and 1930s. A smaller majority of the city’s 223 pedestrian tunnels were built in those two decades. Also, City Councilman Mitch O’Farrell did not say that the Silver Lake Neighborhood Council’s opposition contained no specific proposal for who would might organize a new use for the Silver Lake tunnel. Information about the neighborhood council’s opposition was drawn from a review of a letter the council issued on the topic.

------------

But like dozens of others built in that period, the tunnel has been locked away for years and some regret it was ever built.

“For 13 years, I’ve been trying to come up with a solution,” said Mitch O’Farrell, the city councilman for the area who started work on the issue as an aide to then-councilman Eric Garcetti. “We’ve known for too long that the tunnel was the site of crime, drug use, nuisance activity, filth, you name it.”

Police worried that it would get even worse — that some thug would drag a passerby into the tunnel to rob, rape or kill, O’Farrell said.

“People were always getting in there and doing the most vile things right under Sunset Boulevard,” he said.

For decades, the city has tried to keep the underpass entrances behind chain link. Now, the city council has approved an O’Farrell-authored motion ordering workers to close the tunnel once and for all by designing a permanent, impassible closure — despite objections from some advocates who feel the city might be giving up too easily.

“The city has not done a very good job of creating safe crossings in Silver Lake, so until they do, the tunnels are important,” said Deborah Murphy, an urban planner who runs Los Angeles Walks, a pedestrian advocacy group.

“I don’t like tunnels, but they have some value when you don’t have another good option,” she said.

The tunnels work best in places where there is no other good way to cross the street, and Los Angeles has many locations that fit the bill.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

In places where people regularly use the tunnels, they remain well-tended and calm, including the one servicing nearby Allessandro Elementary School, which is decorated with murals of underwater scenes.

“I don’t know what we would do without it,” said Principal Lynn Andrews. About half of the school’s parking is on the other side of Riverside Drive, and there are no stoplights to help teachers, students and parents cross the busy street without dodging cars.

But voters approved the tunnels during a gentler time with much less crime, and they solved a safety problem that no longer exists.

At the Micheltorena crossing, and many other locations, planners designed the underpasses to help children avoid streetcar tracks.

When the Micheltorena tunnel opened in 1924 at the cost of $10,400, the Hollywood Line still rumbled up Sunset Boulevard. But the trolley rang its last bell in 1954, replaced by buses that come to a halt at a nearby stoplight.

Now, 106 of the city’s 223 pedestrian tunnels are closed. The Department of Public Works could not say how much maintaining the underpasses costs taxpayers, noting that it sometimes hires contractors to remove human waste, needles and other hazardous material.

As urban planners look at new ways to make life easier for pedestrians in places such as Silver Lake, tunnels are not high on the list.

“We think about curb extensions, crossing islands and improved markings for crosswalks,” said Ryan Snyder, a transportation planner and UCLA professor. “Today, you would say tunnels are just an attempt to get pedestrians out of the way of the cars at great expense and sacrificing the convenience of the pedestrian.”

O’Farrell agrees.

“I would argue,” he said, “that in terms of safer streets and more walkable neighborhoods, closing the tunnel actually enhances the experience for pedestrians.”

But even if the tunnels no longer serve pedestrians in many areas, some believe they can be saved for other uses.

The Silver Lake Neighborhood Council voted recently to oppose the Micheltorena closure and to instead explore whether a community partner might be able to reopen the underpass as a seasonal art space or site for cultural events.

One model the neighborhood council considered is the pedestrian tunnel outside Nightingale Middle School in Cypress Park.

Yancey Quinones, the 40-year-old owner of Antigua Coffee Roasters, walked the tunnel as a student at the middle school himself and watched as it fell into decline and then closed in the early 1990s as gangs and the crack epidemic took hold of the neighborhood.

He reopened it in 2012 as an occasional pop-up art gallery, mostly for local Chicano artists. The city signed an agreement that gave him control of the space if he took responsibility for its restoration and upkeep, leaving him to even supply his own electrical power through a generator.

“A lot of people don’t want to go out of their way, but our city and this neighborhood is worth it,” Quinones said. “We need to reclaim our city, and what could be better than a tunnel? You can’t destroy it. Rich or poor, gentrification or bust, this gallery will be able to survive.”

The curator, Gary De La Rosa, said the project drew inspiration from the urban renewal theories of Jane Jacobs, and he dreams that the renowned Chicano artist Frank Romero will one day hold a solo show in the space.

“We need to reuse things and stop throwing them away,” he said. “And I think a lot of people don’t like to hear this, but no one is going to do it for you. Don’t expect the council office to step in. You have to do this stuff yourself.”

The Silver Lake Neighborhood Council’s letter opposing the Micheltorena Elementary School closure included no specific proposal of who might take responsibility, O’Farrell said. After 13 years trying to save the tunnel, O’Farrell said the time has come to concede defeat.

“I would like to cap it off in a way that you don’t even know a tunnel was ever there,” he said.

Twitter: @gtherolf

ALSO:

Caltrans proposes wildlife overpass on 101 Freeway

Public can now see California data on arrests and deaths in police custody

Dramatic rise in crime casts a shadow on downtown L.A.’s gentrification

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.