They vowed to be friends for life. When one died at war, the other fought years to bring him home

- Share via

As kids, Ruben and Raul thought they had life all figured out.

They would grow up and live minutes from one another, be best men in each other’s weddings, godfathers to each other’s children. They would sit side by side at Dodger stadium, two old men in a sea of blue.

The friends never imagined that after high school both would be sent to Vietnam — but only one would return.

The loss was so painful that for 40 years Ruben Valencia could hardly bring himself to say Raul Guerra’s name.

“I put everything about him away,” said Ruben, now 74 years old.

But the past can only stay buried for so long. In 2005, Raul’s remains, which had been missing since his plane was shot down in 1967, were recovered and flown to Hawaii. The plan was to hold them there until U.S. officials tracked down his family.

His family, however, was nowhere to be found.

So Ruben set off on a 12-year quest, determined to bring his friend home. The journey would rattle him. It would teach him things about Raul that likely no one knew, and in the end, it would bring the two friends closer than ever.

Ruben remembers the day Raul walked in as the new kid in his fifth-grade class. He was skinny and shy with a thick head of hair.

Ms. Talbert brought him over. “Raul,” she said. “This is Ruben. He’s going to show you around and be your friend.”

From that day on, the boys were inseparable. They were two sons being raised by two single mothers on the border of East L.A. and Montebello.

They would go to Chroni’s Famous Sandwich Shop after school, split Ruben’s $1 allowance on chili cheese dogs and burgers. They’d walk to Mass together every Sunday. Spend hours lost in their baseball card collections.

“Our moms worked all the time,” Ruben said. “So the two of us, we raised each other.”

Once, in junior high school, a bully challenged Raul to meet him after school and the friends had to think fast. “He’s got two brothers,” Raul said with concern. “Well you’ve got me,” Ruben told him.

Tall and stocky, Ruben showed up on the track that afternoon and kept the brothers on the sidelines while Raul and his rival threw punches and then shook hands.

After graduation, the two tried to plan their future. Raul went to East L.A. College to study sports journalism. Ruben got married and looked for a steady job, one that didn’t require a degree.

But the Vietnam War was raging, and in 1965 Ruben was drafted into the Marines. Raul knew his turn would come, so he enrolled in the Navy.

The friends last saw each other on New Year’s Eve at Ruben’s going away party. Raul was worried. He said: “I wish I could trade places with you.”

“I’m going to be OK,” Ruben told him.

In Vietnam, Ruben was thrown into ground combat at the base of Monkey Mountain, a steep, rugged hill thick with vegetation that he and fellow Marines were dropped into by helicopter.

Raul was miles away aboard a ship; a military journalist waiting for his next big story. When he heard a radar airplane was headed toward Monkey Mountain, he joined the mission.

He didn’t know then that Ruben had already left Vietnam after being injured by an explosive device, and his wife had given birth to a child. He wrote Ruben a letter that summer, telling him he was excited his flight would be passing near Monkey Mountain, bringing the friends closer — if only for a moment.

The day of the mission, Oct. 8, 1967, Raul’s small plane was shot down and all five men aboard were killed. Raul was 24 years old.

The news reached Montebello within days. Raul’s mother, Margaret Guerra, called Ruben. “Please come over,” she said. Navy officials were on their way.

That afternoon, the two cried and sank into each others’ arms. “I couldn’t believe it,” Ruben said. “I was sure he’d be OK.”

The tragedy felt like a final blow — after the war, after the post-traumatic stress he suffered from killing and watching fellow Marines get killed.

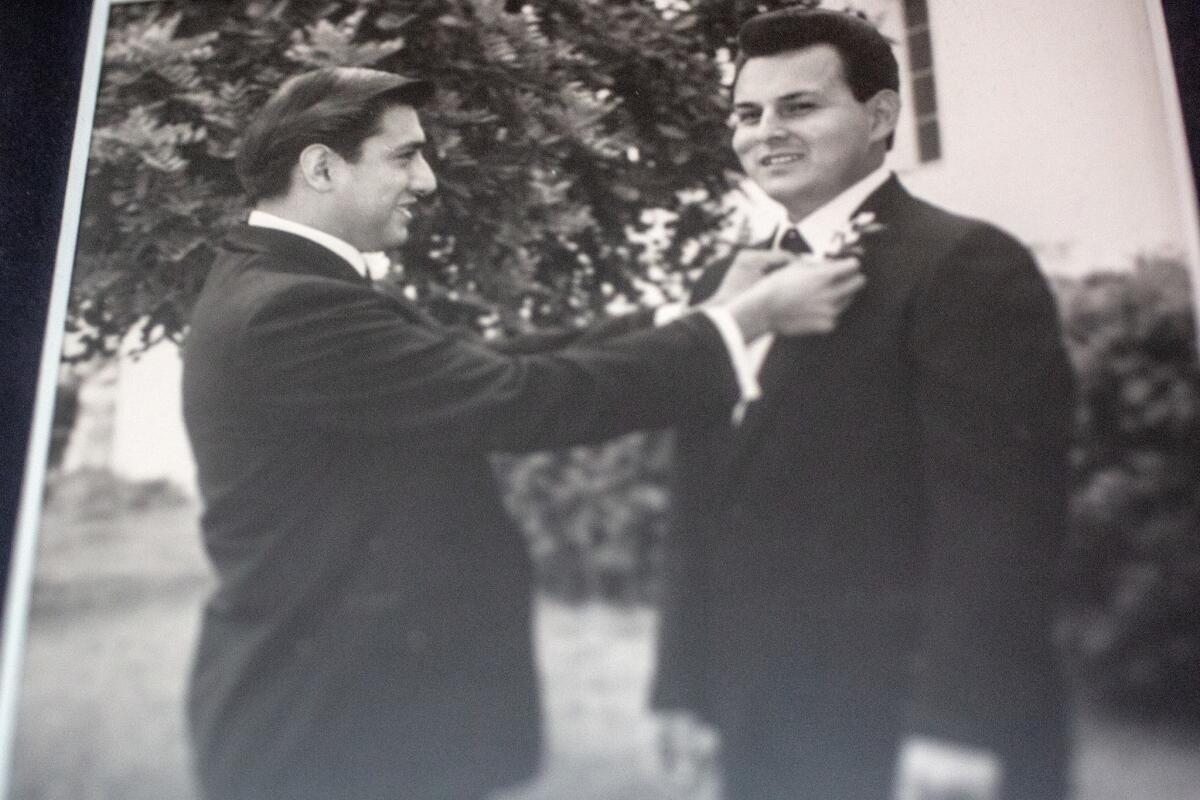

Ruben shut down. He started a new life in Pico Rivera, took a job as a food distribution warehouse manager. For the next 40 years, he avoided anything having to do with war and veterans. He avoided his wedding photographs — when Raul stood proudly by his side as his best man. He never again saw or spoke to Raul’s mother.

“I just couldn’t go there,” he said.

In 2007, while on vacation, Ruben found reason to finally open up.

He got a call from his daughter, Gena Valencia, who had just read the local paper. “Dad,” she told him nervously. “They found Raul’s remains.”

Ruben was stunned. He didn’t know what to say.

From that moment on, all he could think about was Raul. “It’s like he was calling out to me,” he said.

But reuniting with his friend wouldn’t be easy.

The U.S. Department of Defense had made a mistake: They didn’t know if the remains they found belonged to Raul after all.

Back in a forensic laboratory in Hawaii, the investigation was still open. Raul’s case was part of a lengthy list of unresolved cases managed by the government. Some dated back to the Korean War.

Raul’s case was complicated. Military researchers had hit one dead end after another.

It turned out that Margaret, who had died in 1990, was not Raul’s biological mother. Investigators couldn’t track down any trace of an adoption or even his birth certificate from 1942.

“You’d think that since he joined the service, we’d find some kind of paperwork, but we couldn’t,” said Robert Mavis, lead analyst on the case with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, whose duty is to recover missing military members.

Over the years, Ruben constantly called Mavis for updates. “What can I do?” he would tell him. “I need to bring Raul home.”

From his house in Pico Rivera, he did everything to unearth his own clues. He made fliers with Raul’s photo and handed them out wherever he went. He wrote to the Pentagon, the White House, the Department of Defense. He’d go to national missing-in-action conferences and see what he could learn from other families. Each time a high-ranking politician would come to town for events, he’d put a letter about Raul in their hand.

A couple of times, officials in Hawaii found distant relatives, but the candidates weren’t willing to volunteer their DNA. So Ruben, with permission from the military, would call them or drive to their front door. One fellow turned him away. Another was not the right match.

“For so long, I was beating my head against the wall,” Ruben said. “I knew I was never going to give up on Raul.”

In time, a small but dedicated crew of friends, veterans and former classmates joined his crusade. That included the young woman Raul had asked to marry him before he went to war. They called themselves the Bring Home Raul Guerra Committee.

In 2016, the group was so sure their sailor was coming home they began to prepare his funeral. They contracted a mortuary and secured a burial plot.

With help from Mavis, Ruben eventually located a distant nephew of Margaret’s named Todd who was Raul’s next-of-kin. The man was so moved by Ruben’s tale he gave him custody over the remains. Ruben was ecstatic. He went to court and got a judge to sign off on the arrangement.

He was certain this would clear the way with Mavis. But some time later he was told that Raul wasn’t coming home.

Investigators had decided to change course.

That year, the government took the case to top genealogy experts in Utah. Using the latest technology, researchers at Brigham Young University made a final breakthrough.

They traced Raul’s birth to a place outside the United States — 200 miles south in Ensenada, Mexico.

Raul, they found, was a baby born out of wedlock to a woman with Latino roots. Margaret, who was Armenian, was in fact the cousin of Raul’s biological father.

No one knows how Raul came to live with Margaret, but in the 1950s, documents show that she brought the boy across the border into Southern California.

Late last year, officials used these clues to track down three more presumed relatives on Raul’s father’s side: a half sister and two half nephews.

Investigators wanted their DNA, but they were having trouble connecting with the family.

Ruben offered to visit them — this time with a state senator by his side.

Senator Bob Archuleta (D-Pico Rivera), a veteran with vast connections, heard about Ruben’s story and wanted to help. He called Hawaii and reached an agreement with officials:

If he went with Ruben to visit these relatives and they all chose to stand aside, custody of Raul’s remains would be given to Ruben.

Late last year, on a Sunday, the two men headed out to knock on doors. They had three addresses, all within 20 minutes of each other.

At the first and second homes, men came to the door and said they didn’t want to get involved with Raul’s case.

At the third house, an older woman wearing a mumu told Ruben she remembered visiting a relative named Margaret in Mexico once as a child and seeing a little boy there, maybe 2, 3 years old.

She told Ruben she didn’t want to be responsible for the remains, but she wished him well.

That afternoon Ruben finally got what he had fought so hard for: All three relatives had stood aside and he now had a green light to bring his friend home.

As he drove away, however, he didn’t feel relief or joy. He felt bewildered by the family’s cold response.

He thought back to his childhood with Raul. The two never spoke about their missing fathers. Ruben used to tell everyone, “My dad died at war.” He knew that wasn’t true. But the real story was too painful. His father had abandoned him after having an affair with his mother.

Raul told people all the time, “My dad died in Mexico.” Ruben assumed his friend was telling the truth.

He’ll never know. Headed home that Sunday with that familiar sting of rejection, he felt close to his friend. Closer than ever.

“I appreciated him so much,” he said.

On a recent morning, the father of two settled into a chair in his dining room. He smiled and looked at ease.

Spread neatly across the table in front of him was everything he tried to escape for so long: photographs of Raul, their yearbooks from grade school, certificates and news clippings from Raul’s journalism achievements.

He keeps the only photograph he owns of Raul and himself, the one from his wedding day, high above his fireplace mantel, next to his Purple Heart.

“He always understood me,” Ruben said. “All the things I never told other people, he just knew and he understood.”

At this stage in life, he feels some sense of peace, though he still struggles to tell the whole story. The emotions overwhelm him. The day of the funeral at Rose Hills Memorial Park, on April 25, his daughter Gena spoke on his behalf.

It was a service just like Ruben imagined, with a big crowd and full military honors. There were six honor guards, a white horse, a gun salute and the releasing of doves.

Days later, Ruben began his own quiet ritual at the cemetery. It’s located so close to his home he can see it from his living room window.

He took his lawn chair and his lunch and sat beneath the Chinese Elm tree, inches from Raul’s grave.

He and his friend, they had a lot of catching up to do.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.