Forced from Long Beach courthouse, vendor is no longer a no-ware man

Rick Lopez ran the cafeteria and snack bar at the Long Beach courthouse for 20 years. Now he’s set up shop in Downey and Compton.

- Share via

When Rick Lopez packed up the sodas, chips, gum and candy on his final day, he knew he was leaving a lot behind.

There was the security guard who helped him set up shop in the morning and would give him a ride home in the evening, the judicial commissioner who raved that his egg salad sandwich was the best in town, the attorneys who arrived early for the freshly brewed coffee — and even the old, dilapidated Long Beach courthouse itself.

For two decades, Lopez was a fixture there, running the cafeteria and snack bar through a state program that gives blind vendors priority in government buildings.

But when all the judges, bailiffs and clerks moved down the street to a gleaming new courthouse this fall, Lopez didn't make the trip. State officials told Lopez there was nothing they could do to keep him in Long Beach, but they could transfer him to another location. The new courthouse was built by a public-private partnership and developers were given the right to lease out the food stalls as they pleased.

Taking his place would be a food court with chains such as Subway and Coffee Bean.

Lopez was crushed. A courthouse is often a place where some of life's sad and dire dramas play out. But for Lopez, it was also a place where he and a regular cast of characters found ways to bond.

As he walked away from the old courthouse for the last time, he cried.

Lopez, 59, has never married and lives alone in a one-bedroom condo in Long Beach. Every night he phones his 92-year-old mother to catch up.

Blind at birth, he regained some sight in his left eye as he got older. He credits his mother, who prayed over him every day. She would wave her palm over his head, and one day his eyes began tracking it.

"She could never take no for an answer," he said.

You grow where you're planted."— Rick Lopez

In high school in upstate New York, he ran track, always careful to keep his competitors to his left so that he could see them with his good eye.

When he was 23, he left New York to study at a small theology school near Disneyland. He stayed in California, taking odd jobs to make ends meet. During one stretch, he worked as a night-shift manager at a tortilla factory.

When a friend told him about the state's blind vendor program, he applied and landed at a tiny snack bar at a juvenile hall in San Diego, selling chips and sodas. It wasn't until he was transferred to Long Beach several years later that he finally felt at home.

Family members of defendants and victims, along with prosecutors and defense attorneys, came to know him by name. The court interpreters, whose offices were next to Lopez, would come in to get their weekly fix of French fries. He was there long enough that some of those who were called to jury duty for a second or third time became regulars.

Lopez's new shop at the Downey courthouse is tucked into a windowless corner on the first floor where he can hear the constant beep of the security screeners. He is still getting the hang of the register, and the ice machine and freezer are in need of repair. Business is slower, but he's convinced his store will thrive.

"I eat up the years like I eat popcorn," Lopez said of his decades at the Long Beach courthouse. His hair has gone gray, and his constant laughter has carved deep lines in his face. But, he said, "I don't feel old."

He has a knack for remembering names and faces, even of people just passing through. When someone says a kind word, he replies simply: "You're nice."

Lydell Ball, a security guard, looked for him first thing in the morning at the old courthouse and sometimes helped him set out the pastries and get the coffee going. Ball would take Lopez on Costco runs, and Lopez always made sure to stock up on Whoppers — the guard's favorite candy.

Ball misses the vendor.

Lopez went by the new building a couple weeks ago after hearing Ball had been out sick. "I want to make sure you're doing what the doctors tell you," Ball recalled Lopez telling him.

By that time, the old Long Beach courthouse had been shuttered — its escalators still, and a sign advertising Lopez's sixth-floor cafeteria papered over with a misspelled notice: "Serado" — closed.

After leaving Long Beach, Lopez set up shop at the Downey courthouse, a two-hour train and bus ride from home. He wakes up at 3 a.m., dedicating an hour to prayer before heading out the door.

He sees well enough to get around on his own, but has little peripheral vision and no sight in his right eye. Lopez was able to take two of his employees to Downey with him, but the snack bar doesn't have a kitchen, and he had to let his longtime cook go.

His shop is tucked into a windowless corner on the first floor where he can hear the constant beep of the security screeners. He is still getting the hang of the register, and the ice machine and freezer are in need of repair. Business is slower, but he's convinced his store will thrive.

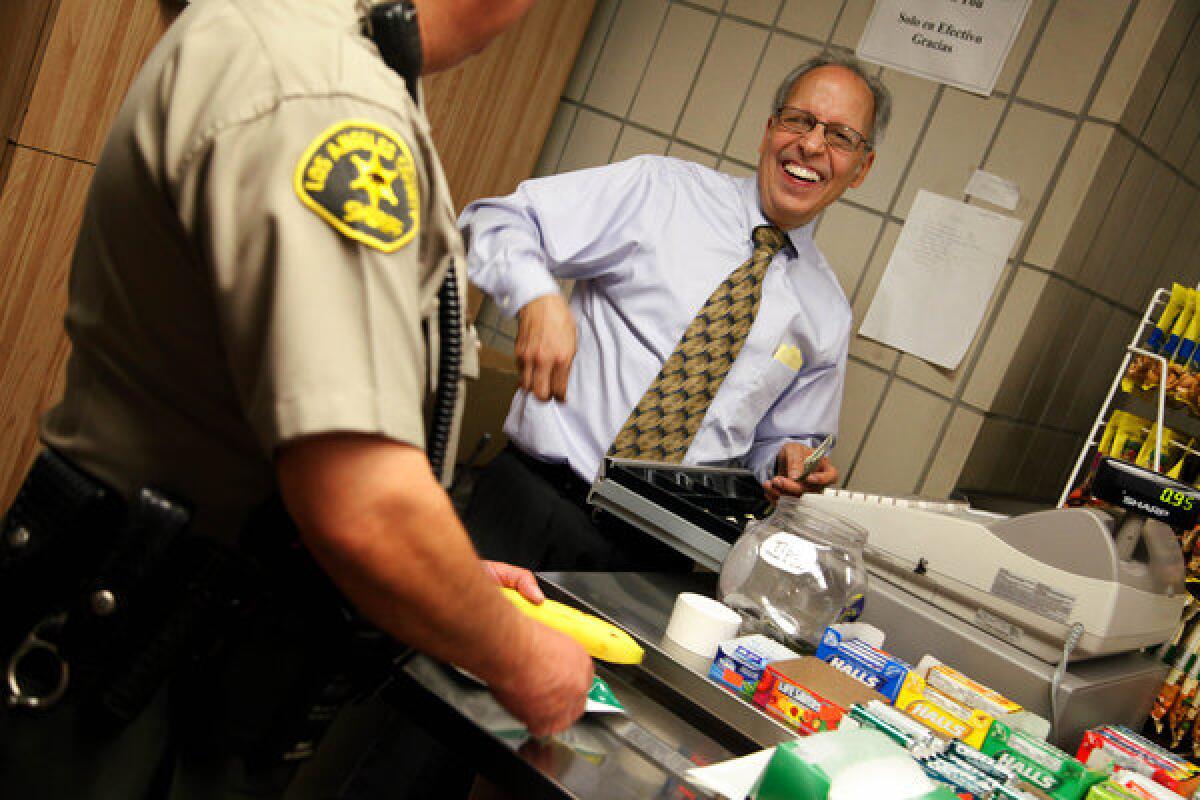

Lopez, right, chats with a guard at the Downey courthouse. He had been praying for sales to improve or another courthouse. Two weeks ago, the state granted Lopez a temporary contract to run the cafeteria at the Compton courthouse, a far busier facility that's closer to home. He'll spend time at both spots.

Shelves that were practically bare when he first arrived are stacked with neat rows of packaged bear claws and doughnuts, the fridge stocked with sandwiches. Near the register, a hot dog warmer clinked as it rotated. "Quarter-pounder, all beef," he said, beaming.

Lopez took apples and plums and rearranged them into neat rows. "We buy with our eyes," he said, looking up.

He is getting to know a young security guard who's about to become a father.

"It's going to change your life," Lopez advised him, patting him on the back. The guard, a foot taller than Lopez and half his age, grinned sheepishly.

During his first couple of weeks, Lopez said, his sales weren't enough to cover his employees' wages; he drew from his savings to pay the bills. He has big plans: a popcorn machine, ice cream, and, eventually, made-to-order breakfast and BLTs for lunch.

"Remember 'Casablanca'? We just have to get a little piano now," said Lopez, his eyes squinting with laughter behind thick glasses.

Still, he said, he had been praying for change — for sales to improve or another courthouse to serve. Two weeks ago, the state granted Lopez a temporary contract to run the cafeteria at the Compton courthouse, too, a far busier facility that's closer to home. He called his cook to tell him he could have his job back. Lopez will spend time at both spots.

One morning, he was walking through the hallway in Downey when he noticed a somber-looking man in line for small claims court. He stopped to talk to him. David Lugo had recently lost his son, killed when the driver of a parked car he was sitting on sped off and ran him over.

Lopez took apples and plums and rearranged them into neat rows. ‘We buy with our eyes,’ he said, looking up.

Lopez listened to his story and suddenly hugged Lugo, a bear of a man, and invited him to the snack bar.

The two talked about faith and purpose and grieving. Before he left, Lopez shook the man's hand and discreetly slipped a $100 bill into his palm to help with funeral costs.

Just after noon, one of the security guards walked in with a nod and retrieved his sack lunch from a refrigerator, leaving a dollar at the register for a cup of coffee.

A few minutes later, a gruff-looking man with a mustache and tattoos on both arms showed up.

"So you took over, huh?" he said, looking around.

"Yeah, I did," Lopez said. "Do you work here?"

"Just passing through," the man replied as he paid for his water and stepped out into the hall to wait.

Lopez has begun to cultivate a new group of regulars. He's introduced himself to court employees and traded laughs with the building manager. Between customers, he recited one name after another, committing them to memory.

"You grow where you're planted," Lopez said with a shrug, and then turned to his register to ring up the next sale.

Follow Christine Mai-Duc (@cmaiduc) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Hall of Fame announcer is the other voice of the Dodgers

Roaming advisor is a key cog in the Capitol machine

He's like the Capitol cat. He hangs around, and no one knows who feeds him."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.