Minecraft offers a virtual way to be with their deported friend

Berkeley fourth-graders create ‘Rodrigo’s World’ in a popular video game called Minecraft to stay in touch with a classmate who was deported to Mexico.

- Share via

To save their classmate who was deported to Mexico, the fourth-graders devised an epic plan.

That Rodrigo Guzman, 10, could no longer be with his friends and attend Jefferson Elementary seemed so obviously unfair to these students. So they started an online petition that got 2,788 signatures. They created a Facebook page and posted videos to YouTube.

They petitioned the Berkeley City Council and school district, which passed resolutions supporting their cause. They met with Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Oakland) to ask whether she could intervene.

"We have to fight for Rodrigo's rights because he is not able to do it himself!" Kyle Kuwahara said in a letter to President Obama. "Today I'm writing to you on Rosa Parks' 100th birthday to do the right thing. To allow Rodrigo and his family to return to their home, school and friends in Berkeley."

Even as the children's "Bring Rodrigo Home" campaign built momentum, it became clear that things would not move fast. The immigration system is complicated, the students were told. There were too many agencies and politicians with rules that didn't seem to share their urgency.

Worried that they'd lose touch with Rodrigo and that he'd lose hope, Kyle and his twin brother, Scott, turned to Minecraft, a video game where they'd forged their greatest bonds with each other.

With the ability to create virtual worlds in Minecraft, one of the unlikeliest video game hits in recent years, these students could create a haven for themselves and Rodrigo.

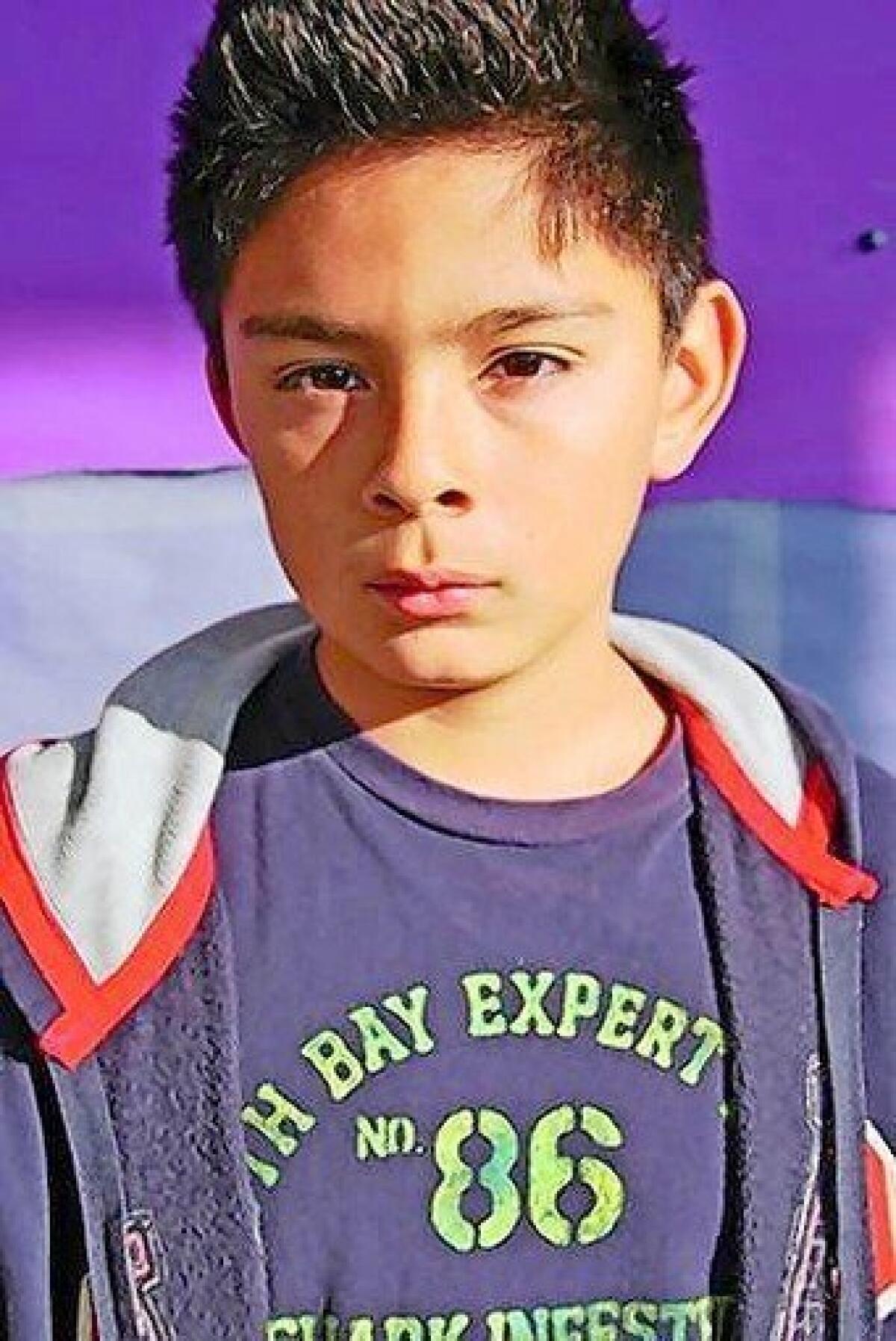

Rodrigo Guzman, 10, lived with his family in Berkeley until U.S. officials took their passports while the family was traveling to Mexico.

It could be a place with their own rules, where it would seem as if their friend was still next to them and not playing from thousands of miles away. A place where the Creepers and Zombie Pigmen still seemed less frightening and confusing than the real world of borders, immigration laws and visas constructed by adults.

They could build "Rodrigo's World."

"We just wanted to be able to hang out somewhere with Rodrigo where none of this other stuff mattered," Scott said. "The more we learn about immigration, the more unfair it seems."

Rodrigo Javier Guzman Diaz was born in Mexico City but had lived in Berkeley since the age of 2. His parents, Reyna Diaz Mayida and Javier Guzman Ponce, traveled here because they had extended family in the area. Diaz Mayida, educated as an accountant in Mexico, cleaned houses. Guzman Ponce worked as a cook in fraternity houses.

This made it possible for Rodrigo to attend Jefferson, one of Berkeley's highest-rated schools. Or it did, until the familiar world his family had built for him was taken from Rodrigo on Jan. 10.

Rodrigo was traveling with his parents to Mexico to renew their tourist visas. On their way, they had a connecting flight in Houston, where they were stopped by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

For reasons the family members say were never explained to them, their Mexican passports and visas were confiscated. They were told to continue on to Mexico, where it would take five years or longer to get new visas.

Almost all the family's possessions remain in Berkeley. Rodrigo finds himself essentially exiled to a land that is largely foreign to him.

"He's very quiet and sad sometimes," Diaz Mayida said in an interview via Skype from Cuernavaca, Mexico. "He misses his friends and his home in Berkeley."

U.S. Customs officials declined to discuss the case, citing privacy laws.

Back in Berkeley, when the school year resumed after winter break, Rodrigo's teacher, Barbara Wenger, was puzzled by his absence. After a few days, word reached the school that Rodrigo's family had been deported and would not be returning.

It was up to Wenger to break the news to her class. When she told the children what happened to Rodrigo's family, one of the students asked a question that broke her heart. She knew that a bit of childhood innocence about the way the world works was about to be lost.

"What's immigration?" a student wondered.

So Wenger explained.

During the school year, the civil rights movement had been part of the fourth-grade curriculum at Jefferson. Students learned how people with little power had organized themselves to change things they found unjust.

For many of the Jefferson students, whatever Rodrigo's parents did or did not do, it didn't seem right that he couldn't be with his friends at the school he'd been attending for years. After learning about the immigration laws and hearing what had happened to Rodrigo, Kyle and Scott Kuwahara told their parents that they and some friends wanted to start a hunger strike on their former classmate's behalf.

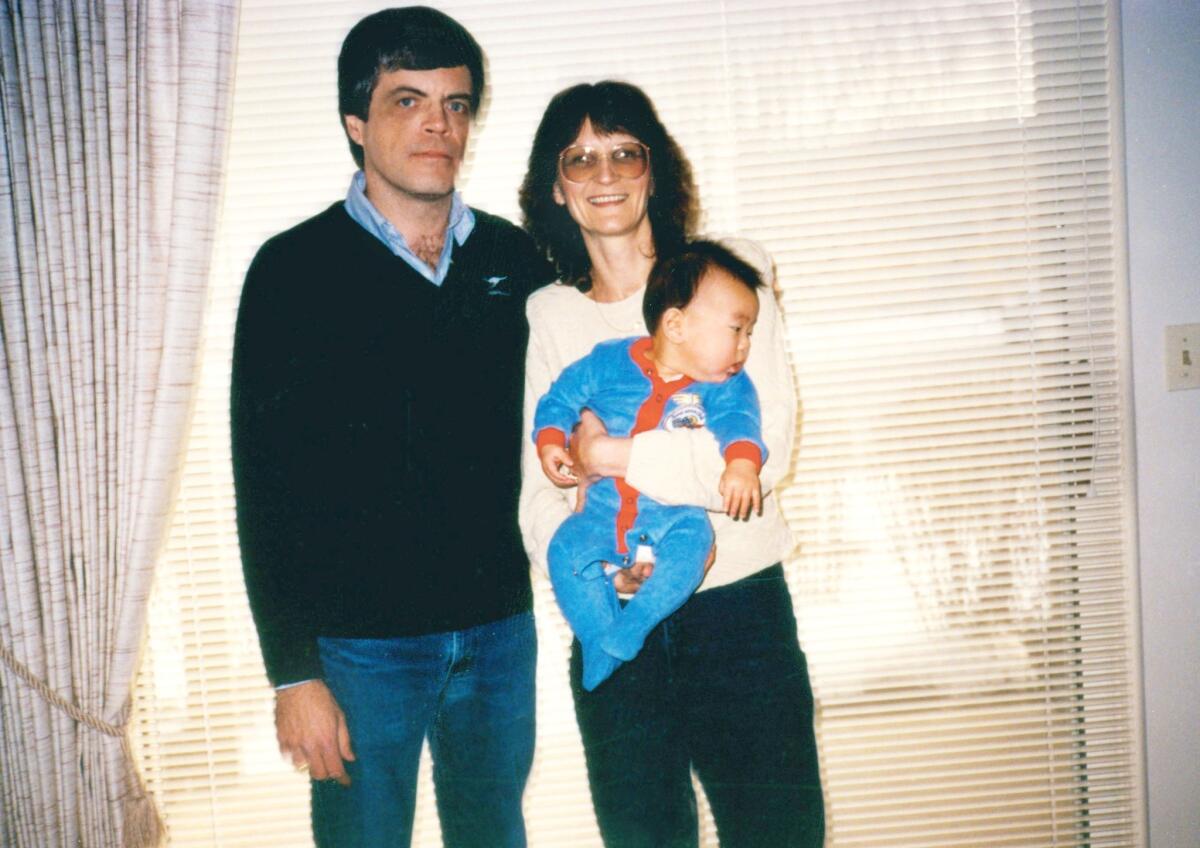

For "Rodrigo's World," the Jefferson students and their families rented a server and installed Minecraft on it, allowing the kids, even Rodrigo, to enter the same Minecraft world. (Craig Kuwahara)

Rather than encourage a hunger strike, their mother, Mable Yee, and other parents helped the students channel their anger into the "Bring Rodrigo Home" campaign that gained widespread attention in the Bay Area. Along the way, the children also turned their attention to Minecraft.

Nobody quite remembers who at Jefferson Elementary first discovered Minecraft, which caught on by word-of-mouth.

Rodrigo and his classmates would meet after school or on weekends at friends' houses, discovering that Minecraft's deceptively simple premise allowed them almost limitless creative possibilities. The game's focus is on players cooperating to build things rather than competing to destroy one another. Players gather or mine material to make tools and construct buildings.

"I like that it lets you build whatever you want," Rodrigo said recently, via Skype. "I can create so much with my imagination."

For "Rodrigo's World," the Jefferson students and their families rented a server and installed Minecraft on it. This would allow the kids, even Rodrigo, to enter the same Minecraft world, their own private haven, from anywhere via the Internet.

"I want to say thank you for this, because it's helping me," Rodrigo said. "But I still hope to come back and see everyone again."

The more we learn about immigration, the more unfair it seems."— Scott Kuwahara

On a Saturday night, about two dozen of Rodrigo's friends and classmates arrived at Mo'Joe Cafe to officially launch "Rodrigo's World."

The children whipped open their laptops, scrambled for outlets so crucial for the long evening ahead and logged into Minecraft. The game's earth-tone palette of browns, grays and greens flashed open on screen after screen, rippling across the cafe. The kids raced from table to table, sharing stories about their discoveries and creations.

Politics and immigration battles took a back seat to the far more pressing task at hand.

As the players plunged into "Rodrigo's World," they stumbled across Rodrigo's avatar, a blocky figure that appeared to be three stacked cubes with two boxy arms and a pixilated face with a few darkly colored squares that hinted at features such as eyes and a mouth.

The real Rodrigo, playing from his family's new home near Mexico City, also appeared in the cafe via Skype, his head floating on a laptop that was passed around the room.

Players mined the materials they needed to craft Diamond Swords and Gold Pickaxes, stronger tools that offered greater protection from the bad guys who roam the land: Endermen, Zombie Pigmen and Creepers.

"I need to find some obsidian!" shouted Scott to the room at large and to Rodrigo on a laptop nearby. Obsidian is a hard-to-find material, highly valued because it's extremely resistant to any attacks or explosions.

It was a productive start. They made a dueling chamber. A giant gold tower. A seething lava fountain. They placed a purple portal that can whisk them to the Nether, the fire-filled pit deep underground that tantalizes with rare and treasured materials.

In the weeks since, some of the students' families have worked with Rep. Zoe Lofgren's office to file a petition for humanitarian parole, a long-shot appeal on Rodrigo's behalf.

The students have continued to explore "Rodrigo's World" in smaller groups, sometimes logging on from home by themselves, sometimes chatting with Rodrigo at the same time on Skype, to refine their initial creations.

Eventually, given time, there may be homes. Perhaps some battles.

For now, at least, it's a place they can find their friend.

Follow Chris O'Brien (@obrien) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

An adopted son discovers more than he expected

I had misjudged the magnitude of this meeting — both for my biological mother and for me."

Brazilian sees museum as 'the Disney of the future'

We are building the...Disney World of culture, the intellect, the environment and research."

A strong voice in Louisiana's Cancer Alley

The guys who work in the plants will tell you they know it killed their dad."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.