Ugly vestiges of ‘the old LAPD’

- Share via

It’s not a good sign when the detective you choose to train other cops uses his class to make crude sexual jokes about a female colleague and yuks it up about shooting a fellow officer to death.

The detective, Frank Lyga of the LAPD’s gang and narcotics division, apparently did that last November in a training session recorded surreptitiously by an officer in the class. The officer filed a complaint against Lyga last fall; the tape surfaced this spring.

In 1997, Lyga, who is white, shot and killed an off-duty black LAPD officer he said menaced him in a road-rage encounter. Neither may have realized the other was a cop. Lyga was exonerated by the department, but the shooting stoked racial tensions that lingered for years.

In the recording, Lyga appears to make light of the officer’s death: “I could have killed a whole truckload of them” with no regret, he recounted telling the lawyer for the dead man’s family.

The training spiel caught on tape also included vulgar remarks about a “cute little Hispanic” sergeant, and used “male black” and “female black” so gratuitously, listening made me cringe.

His tirade ought to make Lyga as much of an embarrassment to the LAPD as Donald Sterling was to the NBA.

::

Lyga’s shtick, considered alone, might not seem like such a big deal. But it’s the third episode in recent months that suggests reforms haven’t changed hearts and minds inside the LAPD.

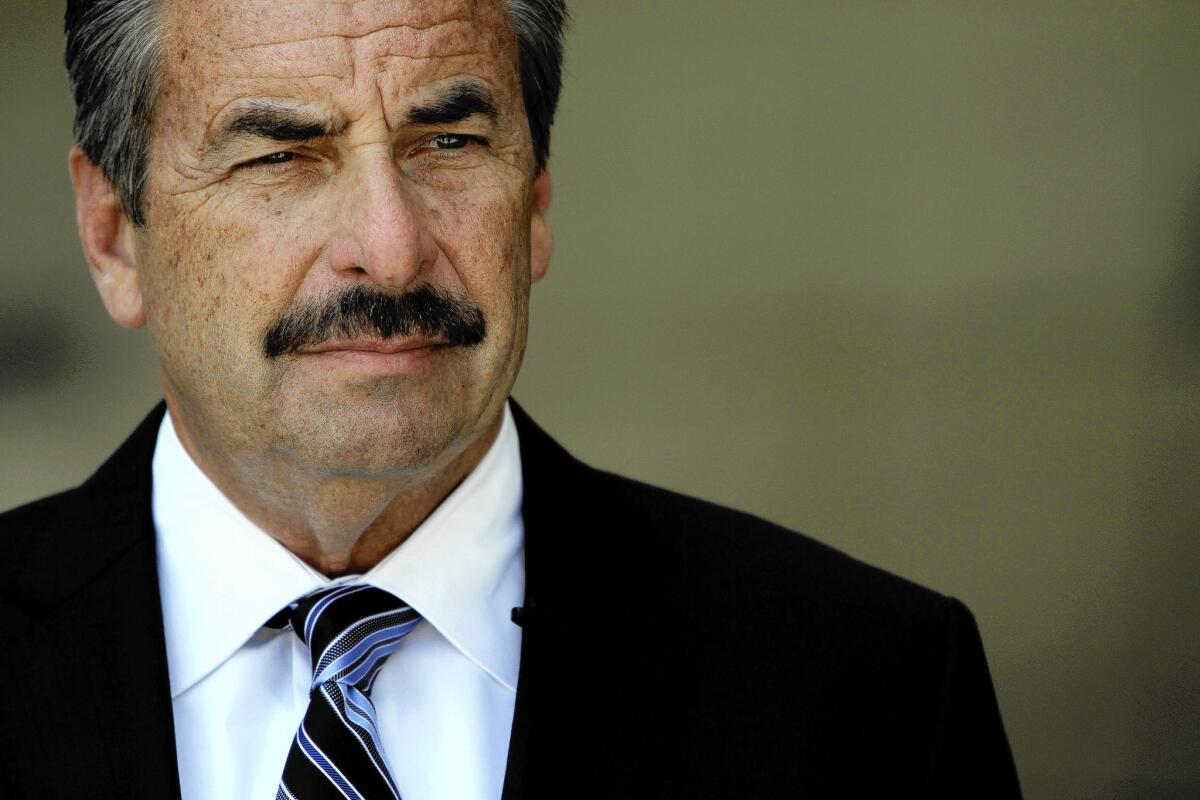

Chief Charlie Beck landed on the hot seat in March, when he refused to fire a white officer who’d gotten drunk off-duty, pulled a gun on a black man who’d danced with his wife at a Norco bar, and used a racial slur to describe the man when deputies questioned him.

The officer, Shaun Hillman — the son and nephew of veteran LAPD cops — then lied about the incident in an internal investigation; he didn’t realize a sheriff’s deputy in Norco had recorded his comments.

A disciplinary panel recommended in January that Hillman be fired. But Times reporter Joel Rubin learned that Beck gave Hillman the equivalent of a three-month suspensioninstead.

A few weeks later, Chief Beck was chastised by civilian police commissioners for not investigating or reporting to them vandalism last summer by South Los Angeles officers, who’d disabled dozens of patrol car recorders installed to monitor their on-duty encounters.

The recorders are the linchpin of Beck’s plan to make officers in every division more accountable to the public. South Bureau was the first to get them, he said, “because that’s where we have the most work to do building community trust.”

Beck was “disappointed,” he said, to learn that officers disabled dozens of the recording devices to avoid being monitored. He didn’t investigate not because he didn’t care — which is how it looked to outsiders — but because it would be impossible to identify the culprits, he said. And he didn’t want the hunt to delay the project’s expansion to other police divisions.

The incidents have become public just as Beck is hoping to parlay a steady drop in crime into a second five-year term. They may be enough to make people wonder if our newly progressive department has begun to backslide. The Police Commission will decide in August whether Beck should be rehired.

The chief gets high marks from residents across the city for his allegiance to community policing.

But Beck has been at odds with police commissioners, who’ve complained that he’s too often reluctant to punish officers for misconduct.

Beck told me that’s a bad rap. “I’ve fired plenty of officers,” he said. But privacy rules don’t allow him to share specifics of disciplinary matters.

Residents of areas that used to be hostile to the LAPD seem to trust Chief Beck, who spent most of his 40-year career in South Los Angeles. Good man. Good heart. That’s what I’ve been accustomed to hearing when I ask around.

Now I’m beginning to hear a different refrain: Same old LAPD.

They see officers resisting reforms, hear of them spouting racial slurs — and if they’re not punished appropriately, the chief starts to look less like a reformer and more like a company man.

::

It hurts to hear an officer crow about killing a black man or consider that a cop might be thinking “monkey” — Hillman’s term — when he tickets me.

That pain is shared in black neighborhoods, where lax discipline of officers is a particularly sore point because of the LAPD’s legacy of bigoted policing.

Beck said he considers these high-profile lapses universally upsetting. “I know these are emotional things and people are not going to feel good about it,” he said. “But I want people to know that I don’t take this lightly, that I have a rationale that makes some sense, even if they don’t agree.”

He walked me through each incident, and explained why he did what he did. He admitted that if he had a chance to revisit the Hillman case, he’d demand that the officer apologize publicly. “I think that would have made a difference,” Beck said. “I know he feels contrite.”

The chief recognizes the fragility of community goodwill. He sees these as bumps on the road to change, not detours backward.

“What I really think, and why I think you’re disappointed,” he said, “is we know we’re better than this.

“What makes me grind my teeth is people saying it’s the old LAPD. I know it’s not. I think everybody knows it’s not.”

We’re also learning that it’s not easy to unseat cynicism on streets where officers couldn’t be trusted — or to dislodge old ways of thinking in a new department.

Twitter: @SandyBanksLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.