Bell plans to shelter immigration detainees

- Share via

Nestor Valencia was 4 years old when he boarded a white van filled with piñatas and entered the United States illegally from Mexico.

Now the mayor of Bell, he sees a little of himself in the thousands of children arriving at the U.S. border and entering detention facilities.

Valencia and other officials in the largely immigrant city are now working with the Salvation Army to create a temporary shelter for detainees who were part of a huge surge of Central American children crossing the border.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

A previous headline on this article said “Bell to shelter immigration detainees.” The city has yet to approve the plan.

------------

“My senses tell me this is the right thing to do,” said Valencia, 49. “We’re not a rich community, but we are wealthy in compassion and humanitarian.”

The reaction in Bell is a marked contrast to Murrieta, where last week hundreds of protesters blocked buses trying to move detainees into a facility in the Riverside County city. The protesters said they didn’t want the detainees in their city, expressing concerns over security and diseases.

While the standoff generated national headlines, the reaction has been far less hostile in other parts of Southern California. The region has the largest population of Latin American immigrants in the country, and some residents feel a kinship with the plight of children.

The city of Coachella last week began taking in donations of food and supplies to send to children at its City Hall and Fire Department. On Tuesday, the city filled a U-Haul truck with donations for a shelter home in the Imperial County.

Councilman Steven Hernandez said he was heartened by the generosity, noting that neighboring Palm Springs has joined in the donation drive.

“We certainly understand the dynamics when it comes to people wanting to better their lives,” Hernandez said. “Our city is 98% Latino. We have a lot of similar stories.”

Officials in Bell, a working-class city of 35,000 best known for its public corruption scandal four years ago, begin quietly talking with the Salvation Army and federal officials about establishing an immigrant shelter a few weeks ago.

If the plan goes forward, Bell’s shelter would house 125 immigrants. Officials estimate that about 57,000 unaccompanied children, mostly from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, have made the journey to the U.S. border since last fall.

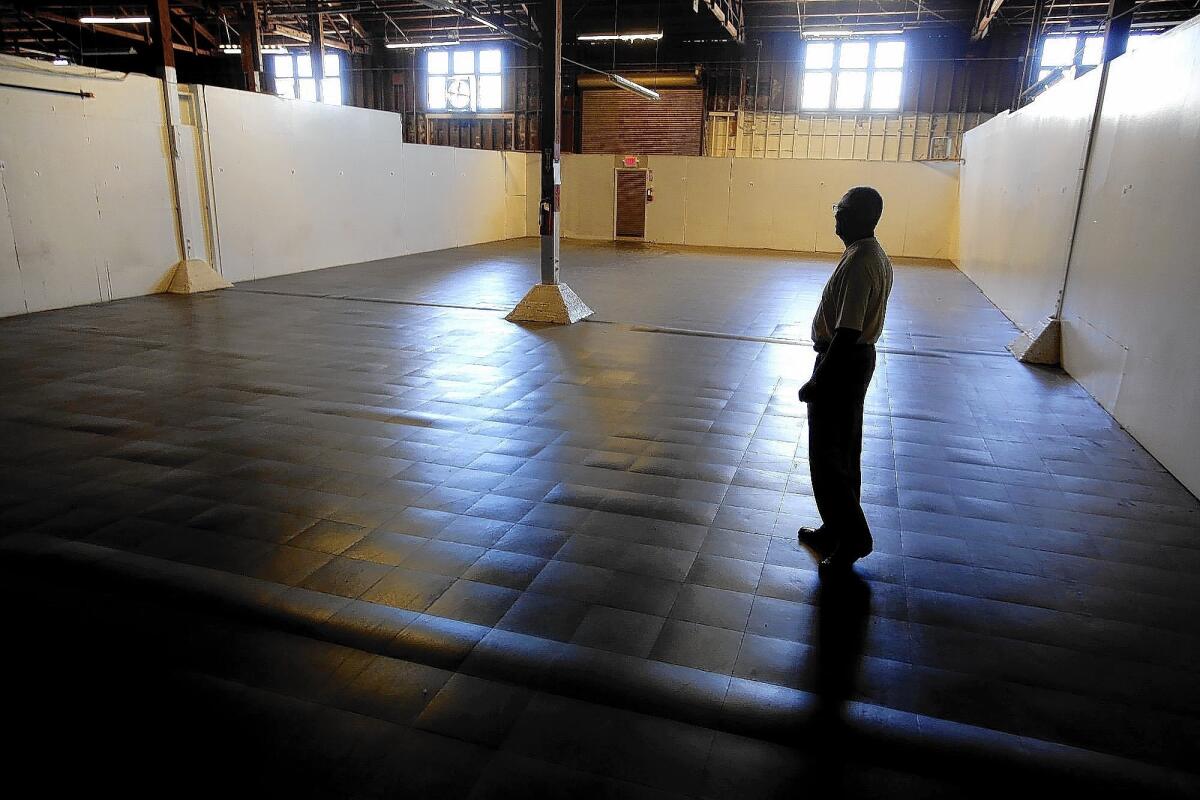

The plan, which the City Council will discuss later this month, is for the Salvation Army to convert shipping warehouses in an industrial district of Bell for use as shelter space. Some of the space is already being used as transitional housing for homeless people.

The Obama administration has signaled its intention to speed up court hearings and take other steps to accelerate deportations. But in the meantime there is a need to find shelters for the detainees. Obama has asked Congress for $3.7 billion to deal with the border crisis, with much of the money to go to expanding and finding facilities to house detainees.

In early July, an email to lawmakers from the White House Office of Intergovernmental Affairs noted that one of the challenges facing the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services was “finding suitable facilities for unaccompanied children.”

A separate email sent to local officials from the Federal Emergency Management Agency asked “if you all have folks in your network that know of suitable facilities in your area.”

Kenneth Wolfe, a Health and Human Services spokesman, said officials are now looking for shelters.

“While only a few facilities will ultimately be selected, a wide range of facilities are being identified and evaluated to determine if they may feasibly provide temporary shelter space for children,” he said. “Facilities will be announced when they are identified as viable options.”

Bell’s efforts have won praise from some politicians in Southeast Los Angeles County, which has a history of advocacy for immigrants who enter the country illegally. Maywood, a small city north of Bell, in 2008 declared itself a “sanctuary city” for these immigrants. The move was largely symbolic but generated some protest both from outsiders and some in the city.

“The critics seem to forget they’re people,” said Veronica Guardado, a Maywood councilwoman who is big supporter of the Bell shelter plan. “I think if we can help out the kids in any way it’s a good idea.”

But on the streets of Bell, reaction has been more mixed.

“They’re coming to this country for a better life, not to purposely create problems,” said David Rios, 55, taking a break from a bicycle ride at Veterans Memorial Park in Bell. “I know there are laws and we should respect them. But sometimes laws are broken out of necessity. We all need to be a little bit more humane.”

But Juan Osmin, 46, of Bell questioned whether his city needs to get involved in an issue that he believes is the responsibility of the U.S. government and those of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. He said policies are needed to prevent the children from coming to the border.

“It’s a delicate situation,” he said. “And the problem is shared by many.”

A similar debate is playing out in Fontana this week. On Thursday, U.S. Department of Homeland Security buses brought 46 detainees — 32 children and 14 adults — to St. Joseph’s Catholic church in Fontana for a temporary stay. There were no protests, and some residents came out to help.

“Many of us in the community came here the exact same way. We went through the same thing,” said Maria Manriquez, a Mexican immigrant who said she planned to donate clothes and food.

But Fontana resident David Nunez, whose mother came to the U.S legally from El Salvador in the 1970s, expressed some misgivings. Although he has no problem with the detainees being sheltered at the church, he hoped they would not stay in the country permanently.

“I’ve got no issue with it as long as they’re not here long-term and you start the deportation process,” he said. “It tears my heart. I have three little ones myself.... But for me, we’ve got to fix this problem. As a country we are already struggling as it is and we need to take care of our own.”

Gov. Jerry Brown weighed in on the crisis Friday, calling on Republicans in Congress to work with President Obama.

Brown also took a dig at Texas during his talk, saying immigrants were rushing to California “because they think it’s great.”

“They may come in through Texas, because they have so many holes in the border down there,” Brown joked. “But they usually want to get over to California as fast as they can.”

In Bell, Valencia sees the city’s new effort to help the children as redemption for the years of corruption that resulted in criminal charges against former officials.

For him, there are also personal reasons.

“There’s trauma crossing the border with strangers,” Valencia said. “But it was my parents’ way of keeping the family together. It was an opportunity. It was a sense of desperation by my parents.”

Times staff writer Michael Finnegan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.