They’re laying eggs at an Oakland restaurant

- Share via

Reporting from Oakland — When the chickens arrived, clucking and pecking, in the rush of Saturday dinner hour -- Witch, Bootsy and five layers to be named later -- they transformed Pizzaiolo restaurant into the latest outpost on food’s frontier.

Many urban eateries boast their own kitchen gardens, with mizuna and Mr. Stripey heirloom tomatoes sprouting on rooftops and busy street medians. Some farms even host top-flight dining rooms, where next season’s prosciutto snuffles placidly nearby.

But chef-owner Charlie Hallowell is nudging the local-food movement into new territory here in the freeway-adjacent gourmet ghetto of a city where Gallus gallus domesticus may be legally raised nearly anywhere. Except at restaurants. That, however, has not stopped Hallowell.

Just off Pizzaiolo’s back patio is a brand-new, custom-built chicken coop. Eggs laid there in the morning will top pizzas by nightfall. Diners will be able to wander over, Barolo in hand, to commune with the creatures that might contribute to their dinner.

The Chez Panisse graduate and his small flock of exotic fowl -- breeds like Buff Laced Polish and Exchequer Leghorn, some with crests like Sunday go-to-meeting hats, others that lay chocolate-brown eggs -- are more than just the epicurean avant-garde.

Oakland is undergoing something of an urban chicken renaissance, and Pizzaiolo is a leading indicator.

The Institute of Urban Homesteading, whose mission is to promote a “more sustainable and more pleasurable way of life,” just celebrated its first anniversary in North Oakland and fills its “Backyard Chickens” classes as soon as they are announced.

Novella Carpenter’s memoir, “Farm City: The Education of an Urban Farmer,” came out in June. It chronicles her move to Oakland’s Ghost Town neighborhood, where she and her boyfriend took over the abandoned lot next to their apartment and cultivated a squatter’s spread amid abandoned cars and homeless people.

The book begins: “I have a farm on a dead-end street in the ghetto. My back stairs are dotted with chicken turds.”

First came the restaurant, which opened four years ago in a gutted hardware store on busy Telegraph Avenue. Hallowell pried ancient linoleum from the floors and pressboard from the walls to reveal century-old Douglas fir and brick. The Dutch Boy paint sign still hangs outside. A wood-fired pizza oven is the hub of the busy, noisy, open kitchen.

The food is rustic, Italian, largely local and hugely popular. Hallowell says he tries “really hard to get drunk and eat food with as many of the farmers I buy from as often as possible,” like Tim Mueller and Trini Campbell of Riverdog Farm in Guinda, Calif., whose Padron peppers often highlight a menu that changes daily.

Then came the clientele, including contractor Max Vogels and architect Chris Andrews, who live within walking distance and meet most mornings for Pizzaiolo’s house-made doughnuts and caffeine supplied by Blue Bottle Coffee Co., an Oakland-based artisanal micro-roaster.

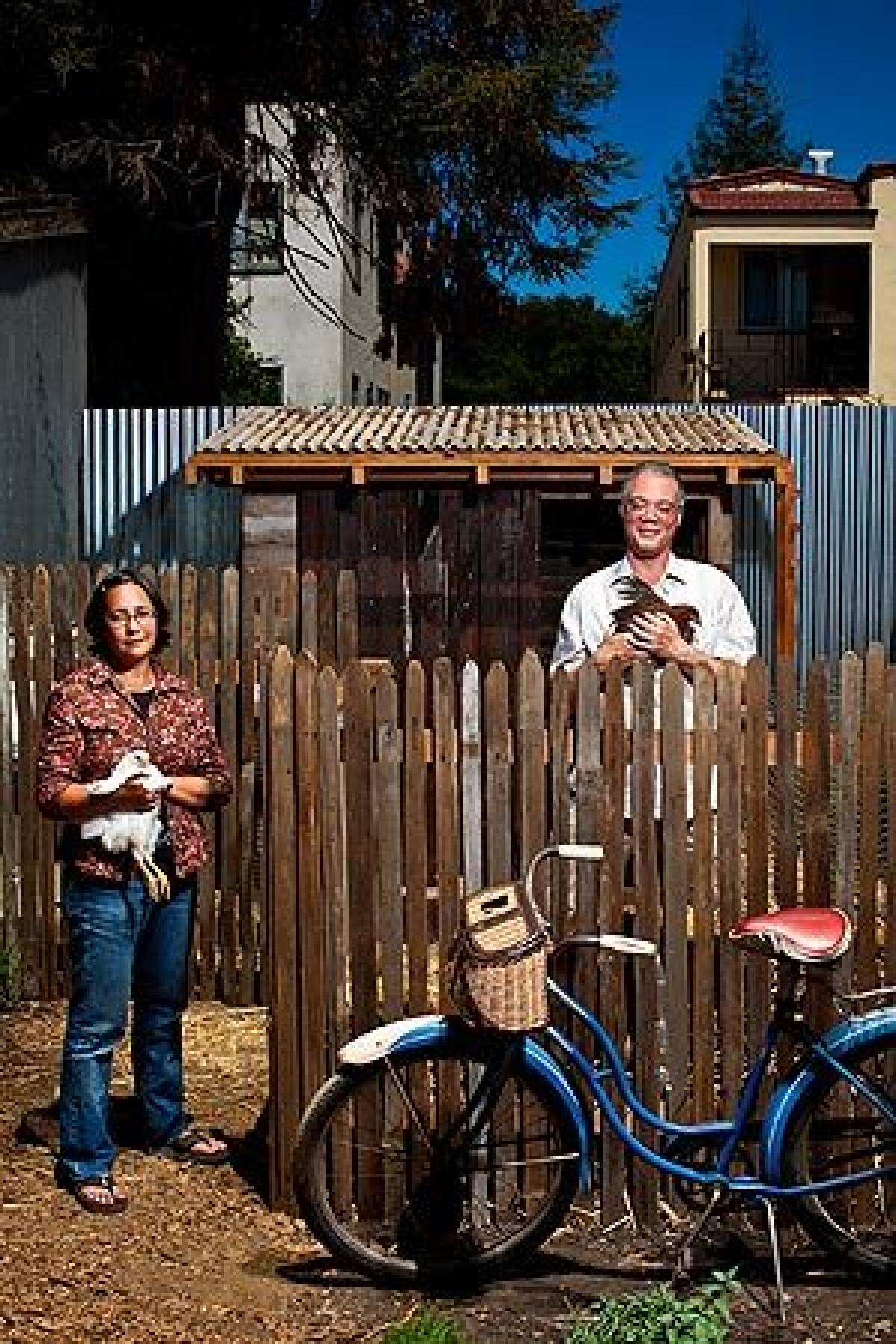

Next came the coop. Andrews, who studied at the Rhode Island School of Design, dreamed up the elegant little structure. “I think the seed was probably planted about four years ago,” he recounts, “when Charlie opened up and saw the backyard space and thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to have a garden back there?’ This year he started talking about it with Max and I. So we thought we’d make it.”

Andrews’ forte is remodeling the region’s cherished Craftsman houses. Vogels is a kind of scavenger-builder who creates out of recycled materials. Andrews describes him as the neighborhood Bodhisattva, “going around figuring out how he can help people.”

The bricks that form the 5-foot-by-7-foot coop’s foundation came from chimneys that used to stand near the restaurant. The siding came from a demolished garage a mile away. The tin roof once graced an industrial building within the city limits. The roost was made from a branch from a neighborhood plum tree.

“There’s a real timeless quality to it, a wholeness,” Andrews says.

Alongside the coop are beehives (inhabitants to come) and, for herbs and vegetables, raised beds made of recycled brick with benches that, as Vogels puts it, invite people to “sit next to lemon thyme and nice smelly plants that are sweet in the evening.”

Once the coop was completed in late July and the chicken run fenced in, it was time to get the birds. Hallowell’s original plan was to take half a dozen of the chickens in his North Oakland backyard -- “full-on yard-bird mutts” -- and transfer them to the restaurant. Andrews and Vogels decided that wouldn’t do.

So earlier this month, they piled into a van and drove to Cotati, an hour north of San Francisco, for an audience with the Chicken Queen, a.k.a. Joan Zeleny. Zeleny specializes in rare and heritage birds and caters to the backyard market. Over the last year, she said, her sales of Cochins, Dorkings, Lace Polish and Rhode Island Whites have risen.

Andrews and Vogels rolled back into Oakland in their chicken-filled van about 8:30 that Saturday night. They pulled up to Pizzaiolo, tucked the birds into the coop and sat down for dinner and a toast: “May these chickens live a long life and be relatively happy in this urban environment.”

One out of two ain’t bad. Bootsy has since died. Her passing was not that much of a surprise; Zeleny warns bird owners that “chickens are like kindergartners and goldfish. If there’s a cootie to get, they will get it.”

The birds are adolescents, so it will be a month or two before they start laying. And even when they do, Hallowell acknowledges they will not produce enough eggs to fully supply a restaurant as busy as his, which each week runs through hundreds of pasture-raised eggs from the Capay Valley.

“We serve 250 people a night, even on a slow night,” says Hallowell, 35. “We can’t have enough chickens to supply us with eggs. We can’t grow enough herbs . . . It’s a token. We can maybe serve six eggs a day until the health department shuts us down.”

It is a meaningful token in a restaurant that makes a point of telling diners where their food comes from. One recent menu offered “Star Route Farm garden lettuces,” “buttermilk-fried Hoffman Farm chicken” and “Bellwether Farms ricotta ravioli with wild nettles.” The health department issue is a little murkier. Chickens are welcome in Oakland as long as they are 20 feet from houses, churches or schools, says Megan Webb, director of Oakland Animal Services. But they are not allowed at hotels, apartments or restaurants.

The folks at Pizzaiolo -- like many urban homesteaders -- tend to have an “ask forgiveness, not permission” attitude. Hallowell says he would fight to keep his flock, if it came to that.

But he doesn’t think it will. “ Alameda County is really liberal,” he notes, happily. “You can grow 70 pot plants. Why not chickens?”

If a restaurateur can pull this off anywhere, it’s probably Oakland’s Temescal neighborhood, where diners like Tove Jensen have embraced the birds.

“This is so cool,” she said, squatting in the straw-covered chicken run and snapping photos. “Chickens in the city! Cool.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.