Rancho Boca de Santa Monica’s family connections

- Share via

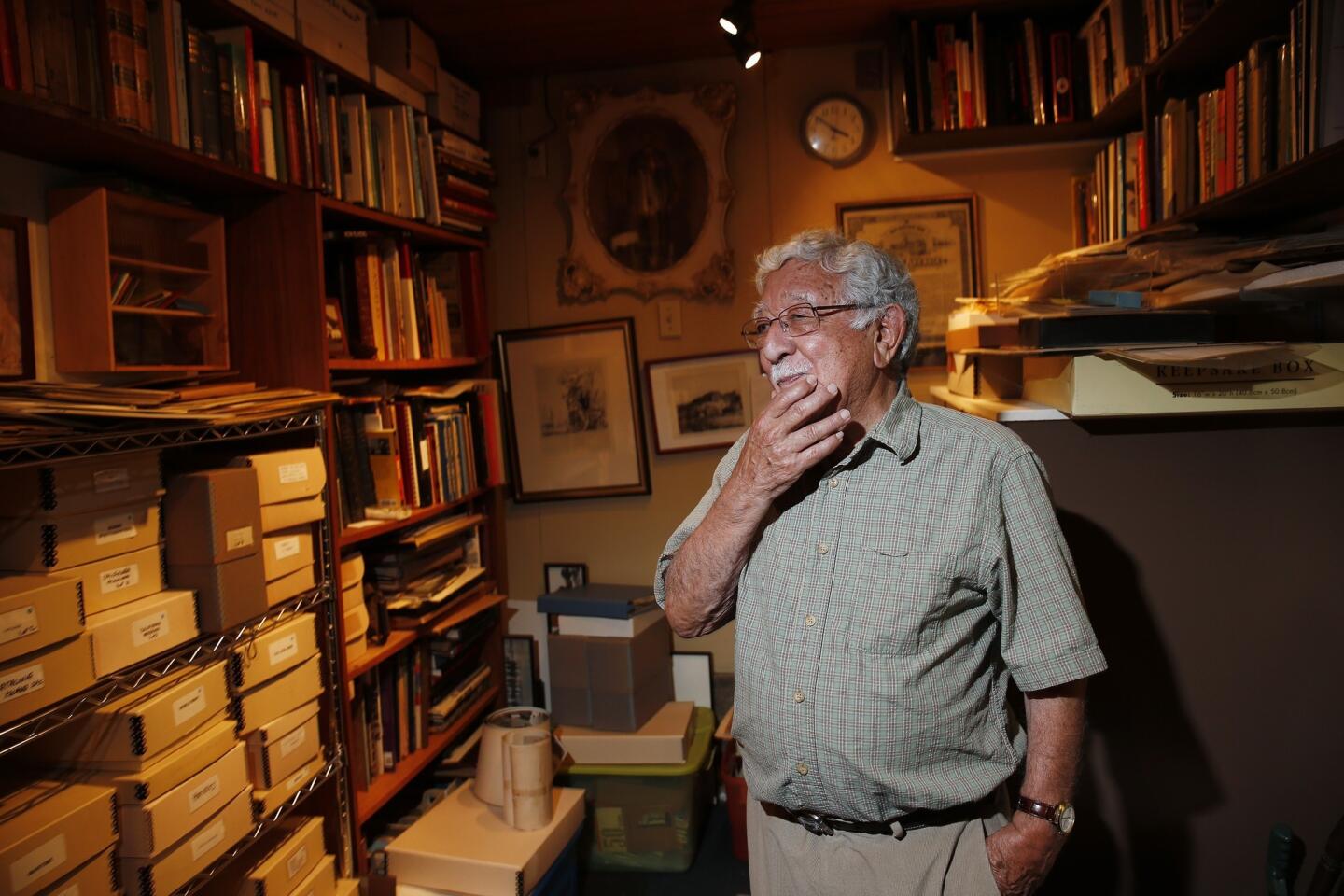

At long-ago gatherings of Los Angeles historians, Ernest Marquez was simultaneously impressed and dismayed to meet people who knew more about his rancho ancestors than he did.

A curator from the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History could rattle off in order the names of descendants of Marquez’s great-grandfathers, the holders of the Mexican land grant that encompassed Santa Monica and Rustic canyons and parts of Pacific Palisades and Santa Monica. A genealogist could recite details about more than 200 offspring of Los Angeles’ original pueblo families.

Dazzled by their knowledge, Marquez intensified his search to learn about his clan’s past, a saga of ingenuous rancheros who relinquished property to cover taxes, lost it to eminent domain or sold for pennies on the acre to Americans who grew rich carving up the land to house eager arrivals to the Golden State.

Marquez found that historians had inexplicably left his family out of their great books about Old California. So he learned to forage for facts and artifacts at libraries, antique shows and flea markets. He tapped the knowledge of scholars.

Now, at 89, with a number of books to his credit, this white-haired, mustachioed chronicler is racing against his own mortality to write the definitive narrative of his family’s 244-year connection to the region. He’s also seeking a home for the thousands of items he has collected. His goal is to ensure that his people’s contributions are recognized, however belatedly.

“Historians have ignored my family’s role,” he said. “I want to correct that.”

::

Years after his forebears had sold off most of the Rancho Boca de Santa Monica, Marquez grew up in the heart of it — Santa Monica Canyon. Marquez paid little heed to the family lore he heard as a child.

He graduated from Santa Monica High School, then served in the Navy during World War II. After working for a time in New York as a freelance cartoonist for Collier’s, Saturday Evening Post and other magazines, he returned to Southern California.

As he and his wife, Lois, raised their family in the San Fernando Valley, Marquez grew more curious about his ancestors.

Finding answers was not easy. Many old-timers, including his father, were long gone, and surviving relatives had faulty recollections.

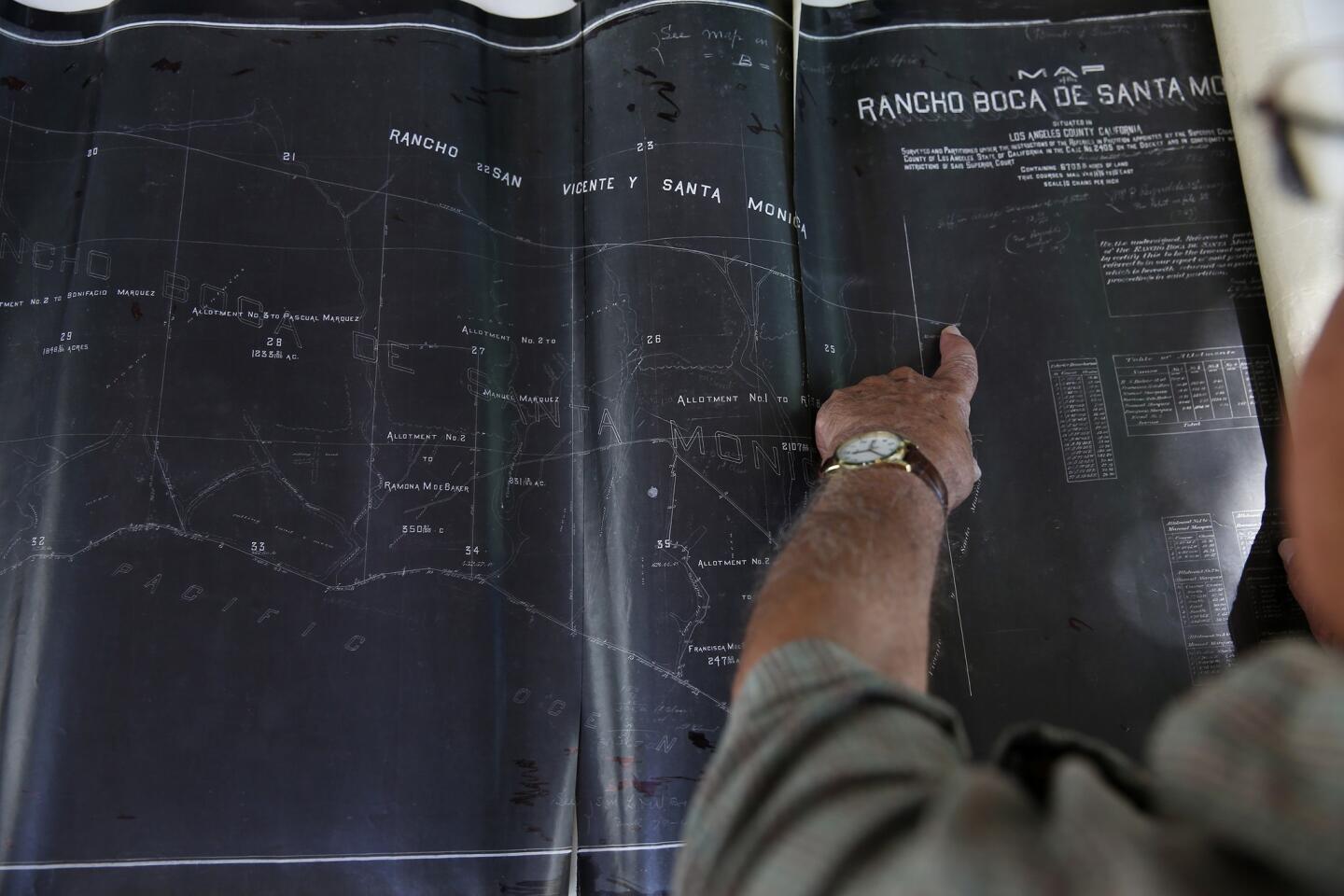

Marquez wrote to the National Archives. An archivist sent a map and a photostatic copy of the 1881 patent for his forebears’ land grant. Near the end of the meticulously penned document appears the name of President James A. Garfield, who approved the patent after being wounded by an assassin.

Marquez supported his wife and three children as a commercial artist for aerospace companies. From the 1950s through the 1970s, he trolled antique stores and postcard shows in Southern California for photographs and maps to build his collection. At a rare-book dealer’s, Marquez found 1850s documents showing the ear markings and brands his great-grandfathers had used on their cattle.

Riffling through countless sepia-tinged snapshots, he sometimes spotted family members. In one photo, his father, Pascual, and other relatives — one with a toddler on his knee — sit high in a sickly looking fig tree as they take a break from pruning. Another shows Pascual atop “arch rock,” a natural formation later destroyed to allow trucks to travel on Pacific Coast Highway.

In the 1970s, Marquez joined the Los Angeles Corral of Westerners, a group dedicated to history and research. He met professors and other collectors, including one who owned originals of his great-grandfather Ysidro Reyes’ will (which listed hundreds of dollars in debts to merchants and left his land to his widow). That collector also had a map showing where Reyes had lived in the original Pueblo de Los Angeles. Just before he died, he sold Marquez the items.

Amid Carrie Estelle Doheny’s vast collection of Western Americana, Marquez found a 1781 letter written by Father Junípero Serra about the marriage of his great-great-great-grandfather, Francisco Reyes, at the San Gabriel Mission. The San Francisco archdiocese had an undated letter in which Francisco Reyes complained to the governor of California that another ranchero had some of Reyes’ horses and would not give them back.

Marquez reached well beyond his own family’s ephemera. In addition to records of Santa Monica Canyon and environs, he acquired panoramas of Palm Springs from 1930 and Tarzana from 1948.

He bought land deeds from the Spanish-Mexican rancho period and a large panoramic photo of the opening of the Owens Valley aqueduct in 1913. He found rare early stereo photos of downtown Los Angeles by William Godfrey, a pioneering photographer.

“You might say while researching my family I became addicted to collecting,” Marquez said. He hid his purchases from his wife because, he said, “I knew she’d get mad as hell.”

It’s “a very important and reasonably valuable collection,” said Michael Dawson, a rare-book dealer who recently cataloged the contents. “It’s a very comprehensive look at a particular region.”

Dawson and others are in search of a home for the assemblage, minus items directly pertaining to the family, which Marquez intends to leave to his three children.

“We’re really proud that he … is the keeper of the family legacy,” said Monica Marquez, his younger daughter. “If ever I need to learn about an obscure relative, my father is no more than a phone call away. He knows all.”

When Ernest was born in 1924, his parents lived next to Canyon School in a bungalow with fruit trees and a chicken coop. (Years later, the city of Los Angeles seized the property and paid Marquez’s mother $5,000 for the home, which was razed to enlarge the school grounds.)

By the time he started first grade, many white residents — sculptors and engineers among them — had moved into the canyon. As the child of Mexican rancheros, he sometimes felt like a second-class citizen, accepted as a friend but never invited to birthday parties.

During his years at the school, Marquez’s mother stored every drawing and scrap of schoolwork. Years after her death, he discovered the items, which became the basis for his book “Memories of Canyon School 1930-1936.”

Seeing the schoolwork revived Marquez’s Depression-era memories of clapping erasers, performing the “Mexican Hat Dance” for classmates and hearing teacher Verna Weber read each day from classic novels as “Ride of the Valkyries” spun on the phonograph.

“Miss Weber,” as the pupils called her, led field trips, pointing out pollywogs and watercress in the creek. Sometimes the children ventured to the weedy cemetery on the upper mesa, where a headstone marked the grave of Pascual Marquez, Ernest’s grandfather, who died in 1916.

::

Marquez likes to say that his Santa Monica Canyon ancestors lived successively in three countries — Spain, Mexico and the United States — without ever leaving home.

In 1769, Marquez’s great-great-great-grandfather Francisco Reyes, a soldado de cuera (leather-jacket soldier), journeyed to Alta California to help establish Franciscan missions and claim the land for Spain. Soldiers gave the name Santa Monica to a mountain creek that flowed to the Pacific.

After Mexico won its independence from Spain, Reyes’ grandson Ysidro and his neighbor, Francisco Marquez, were granted 6,656 acres of the Rancho Boca de Santa Monica (mouth of the Santa Monica). They built the area’s first permanent structures.

Where landmarks such as the Getty Villa now stand and where fitness-minded Westsiders scale worn wooden staircases amid high-tone manses, the families grazed cattle, raised goats and grew fruits and vegetables. But devastating drought in the 1860s killed herds. Large estates were chopped up and parceled out to heirs.

In 1873, Ysidro Reyes’ widow sold much of her property for $6,000 in gold pieces to Robert S. Baker. (Two years later, Baker and a partner laid out the town of Santa Monica.)

Marquez and Reyes family members intermarried and lingered in the canyon. One 1887 photo that Marquez found shows family members welcoming vacationers in bowlers and boaters to the Pascual Marquez Bath House. In another shot, grandfather Pascual takes a moment out from preparing a Mexican barbecue to pose with guests from the Native Sons of the Golden West.

In the 1920s, the families sold most of their remaining rancho property to Santa Monica Land and Water Co., which subdivided it for houses.

Just two known vestiges of the original rancho remain in family hands: a cousin’s house on Entrada Drive, where tax bills are still addressed to Rancho Boca de Santa Monica, and the family cemetery, which volunteers have restored. Earlier this month, a film called “Saving a Sacred Rancho in the Canyon,” about the long, successful battle to save the historic cemetery on San Lorenzo Street, won the best documentary award at the Santa Monica Film Festival.

On a recent visit to the burial ground, Marquez talked about the enormous task he has set for himself. He is 400 pages into the treatise about his family and the rancho. Some of the vast knowledge he has gleaned through decades of research is beginning to fade from memory.

He sat on a fallen acacia near his grandfather’s grave. The dessicated trunk stretched along the ground, then bent toward the light. From its tip sprouted slender, healthy leaves.

Marquez has asked his children to bury his ashes nearby.

“I’ll be there close to my grandfather,” Marquez said. “I’ll be like this tree, dead but still alive.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.