Wind is the culprit in 2017’s horrific wildfire season

- Share via

When Forest Service meteorologist Tom Rolinski heard that a wildfire had broken out Monday evening in Ventura County, he knew it was going to be bad.

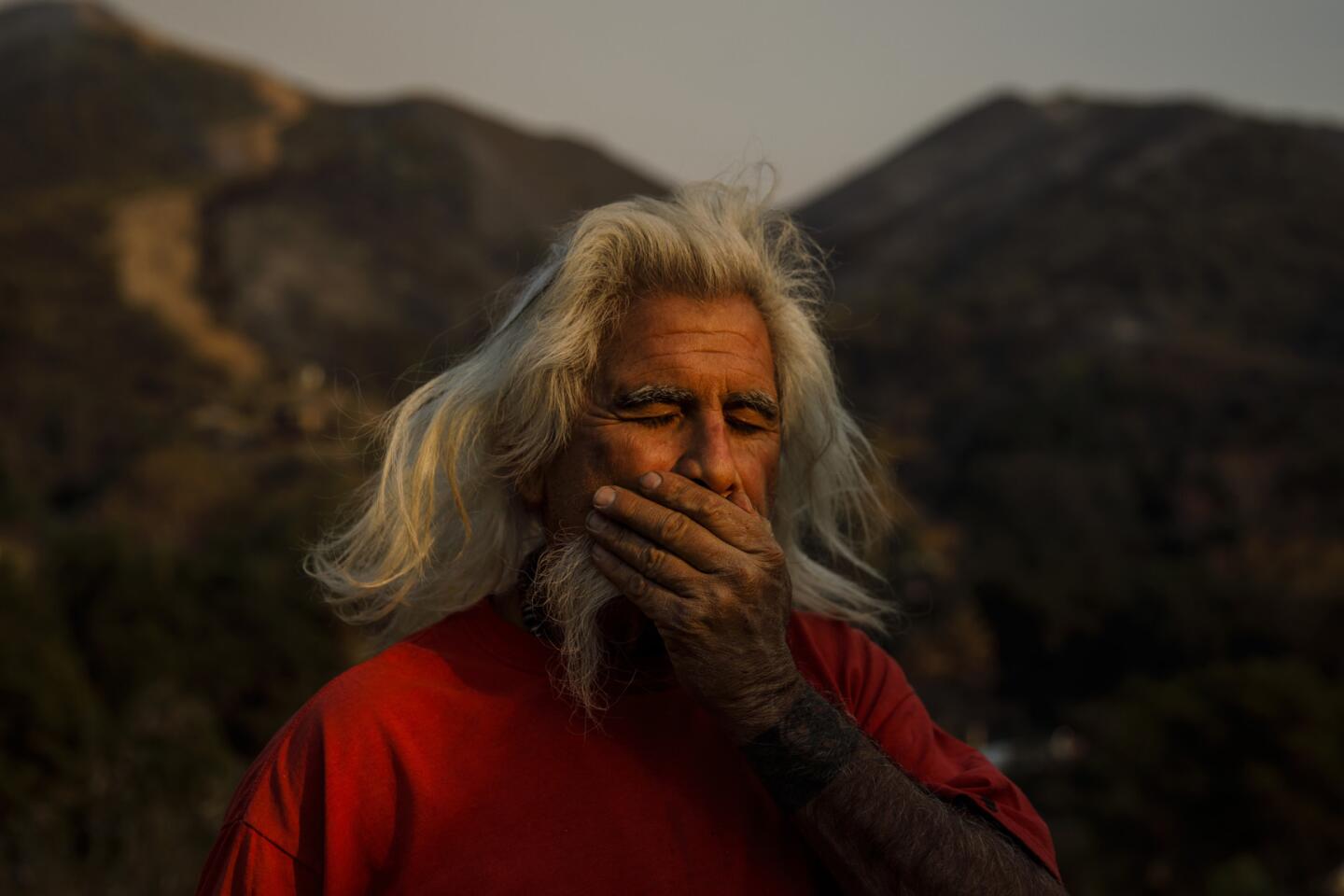

The Thomas fire started in a known wind corridor on the first day of dry Santa Ana winds that are expected to buffet Southern California through the weekend. What’s more, it has been a good eight months since a decent rainfall soaked the chaparral hillsides.

“Fires will spread very rapidly in these conditions and basically will be uncontrollable,” Rolinski said.

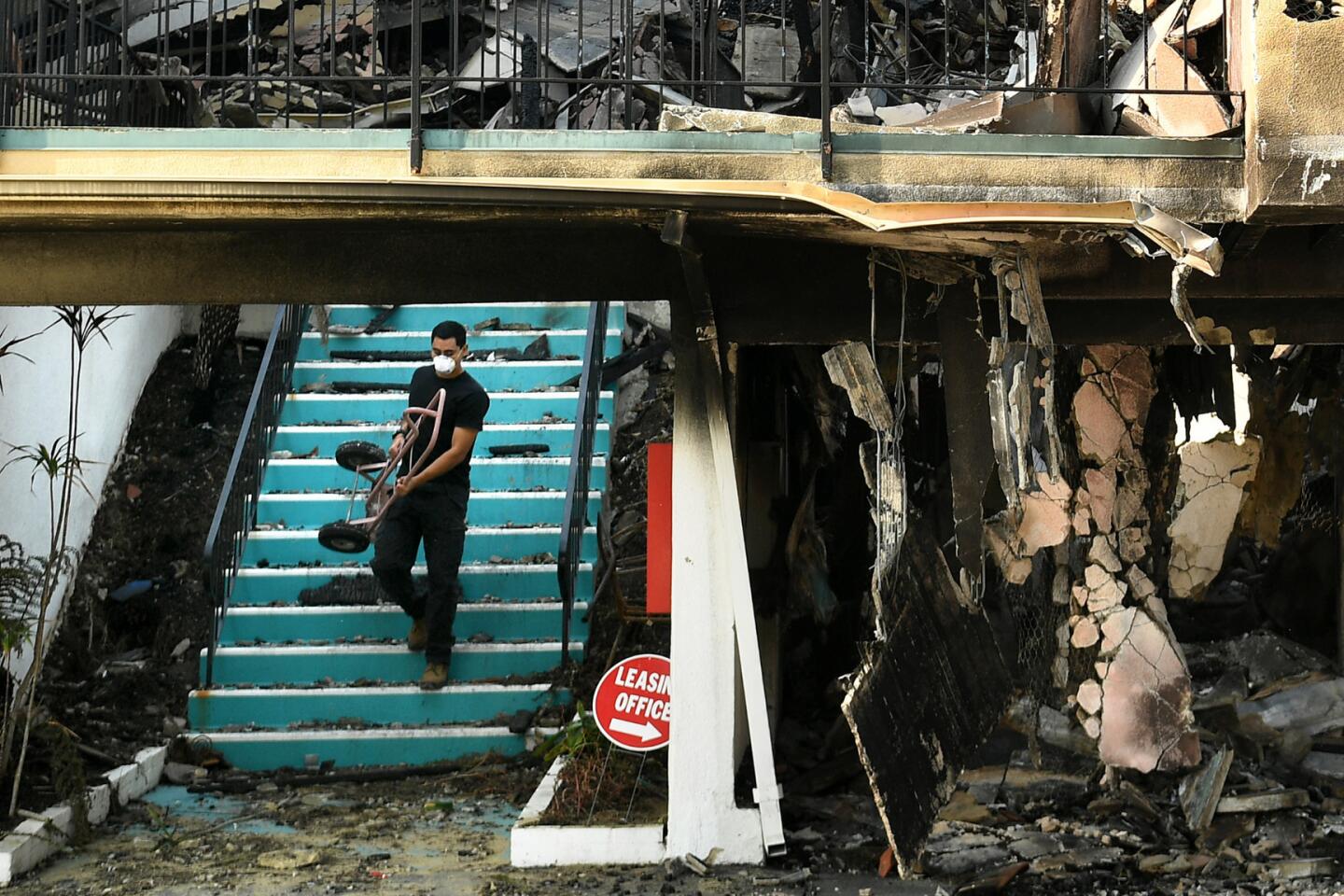

By Thursday morning, the Thomas fire had scorched nearly 100,000 acres and destroyed scores of homes in the Ventura area. It was yet another in the string of harrowing wildfires that are searing 2017 into the state’s record books.

They all have had one thing in common — fierce dry winds from the interior that quickly turn a fire into an inferno.

More than drought or heat, winds can determine whether California burns or doesn’t.

October’s devastating Northern California fire wildfires exploded on a night when Diablo winds raged across eight counties. The fire siege claimed 44 lives and incinerated 8,900 buildings. More than 5,600 of them burned in the Tubbs fire, which now tops the list of the state’s most destructive wildfires.

Southern California managed to escape major wildfires during the final years of the state’s big drought because the Santa Anas didn’t blow much.

But this year is different. Fire meteorologists predict an above-average number of Santa Ana wind days this fall and winter.

There were 14 Santa Ana days — more than twice the norm — in October, when the Canyon 2 fire in Orange County burned dozens of buildings. December typically brings 10 Santa Ana days. By the end of the week, the region will already have been hit by six of them.

The fire danger was expected to peak Thursday, when the online Santa Ana Wildfire Threat Index placed Orange County, the Inland Empire and San Diego County under extreme fire threat and Los Angeles and Ventura counties under high threat. Not since October 2007 — when disastrous fires struck the region — has so much of the Southland faced extreme conditions.

Southern Californians need to be prepared, said Rolinski, who helped develop the index: Plan an escape route; know where family members are; make sure cellphones are charged.

“We’ve seen this over and over again. When that [online map] lights up and we get a fire in a wind-prone area, it’s going to be very difficult to control.”

Indeed, when the winds are in full force, firefighters don’t even try. They concentrate on defending structures and people.

It’s too dangerous to fly retardant- or water-dropping aircraft in high winds, which are also likely to blow any such drops off target.

Though fire officials often say wildfires are tougher to fight in dense scrublands that haven’t burned in decades, wind-driven fires ignore the boundaries of old burns.

Researchers who studied the 2007 fires found they blackened more than 50,000 acres that had burned a mere four years earlier during the region’s hellish 2003 fire season.

As for why this Santa Ana season is ramping up after several years of calm, Rolinski says the answer lies in sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. In the last six months, that part of the sea has cooled, influencing weather patterns conducive to Santa Anas.

The cooler sea temperatures can cause high-pressure systems that push storms to the north and then down into the Great Basin east of California.

The air in the higher-elevation interior is colder than at the coast, creating a pressure gradient that pulls air masses west. As they blow downslope to the coastal areas, they pick up speed, dry out and sometimes heat up.

This week’s winds have been relatively cool — about the only good thing you can say about them.

The current prolonged Santa Ana event is a function of the high-pressure ridge that is sitting over California, said atmospheric scientist Scott Capps, the principal of Atmospheric Data Solutions.

The fact that the winds started in Ventura County and are working their way south is typical, he added.

Wind strength can vary dramatically depending on the local topography. Tuesday morning, a weather station in the Santa Ana Mountains in Orange County, near Capps’ home, recorded gusts of 80 mph.

They tore the roof off his backyard chicken coop — but the chickens were safe.

Wednesday there was a lull in the winds, allowing fire crews to make air drops and to begin to build containment lines around the Southland blazes that broke out this week.

On Thursday afternoon, the 7,000-acre Rye fire near Valencia was 15% contained; the 12,605-acre Creek fire on the edge of the San Fernando Valley was 10%. The Thomas fire was 5% contained, and the Skirball fire, which gnawed at multimillion-dollar homes in Bel-Air, was 20%.

As for whether climate change will diminish or strengthen Santa Ana seasons, there is conflicting research.

“It’s a tough question,” Capps said. “I could see it going either way.”

Just ask UCLA atmospheric sciences professor Alex Hall, who participated in studies that arrived at contradictory conclusions.

“I would say there’s not high confidence in any of these results because they do conflict,” he said. “What isn’t controversial is that we expect [Santa Anas] to be hotter and drier.”

Twitter: @boxall

UPDATES:

Dec. 7, 2:50 p.m.: This article was updated with new fire statistics and threat information.

Dec. 6, 3:05 p.m.: This article was updated to include comment from UCLA atmospheric sciences professor Alex Hall.

This article was originally published at 6 a.m on Dec. 6.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.