Man and myth, Part I: Uncovering the legend of Big Willie Robinson

- Share via

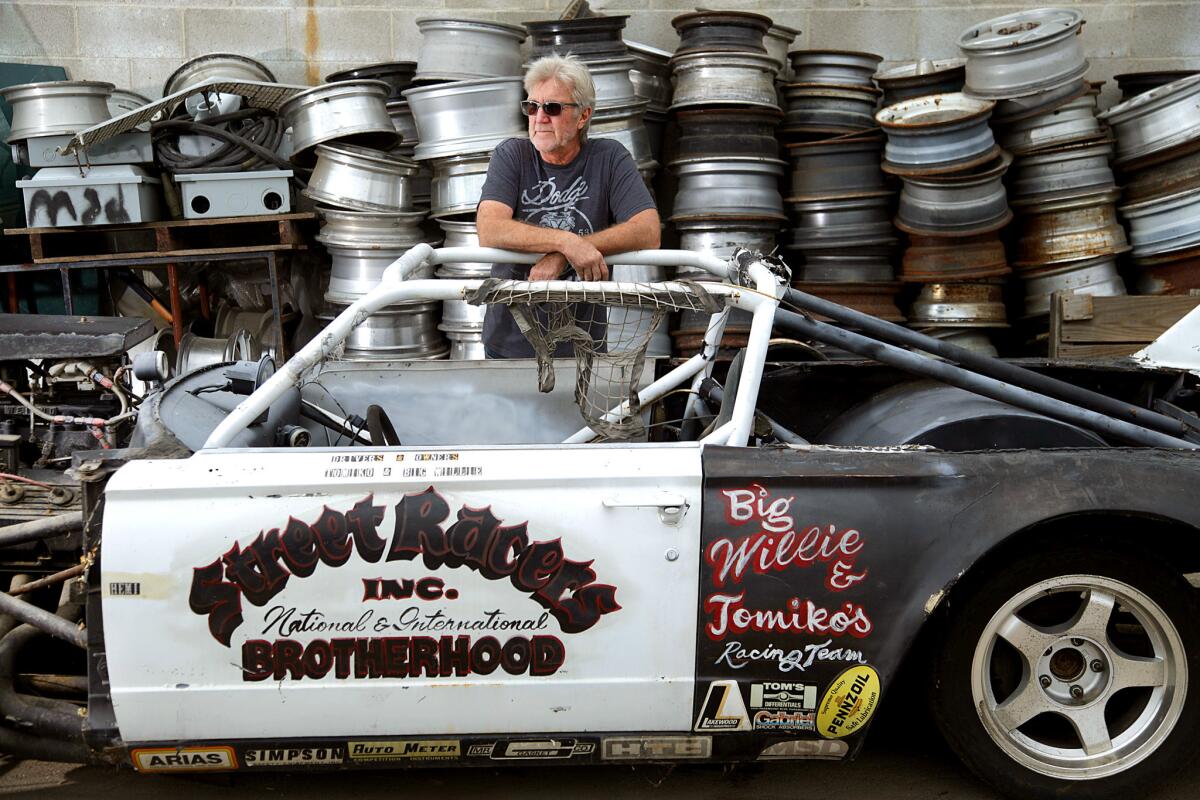

I first heard the name Big Willie Robinson when I spotted a race car that looked like it had been through a war. The roof was missing, the body battered. Its footwells were thick with cobwebs.

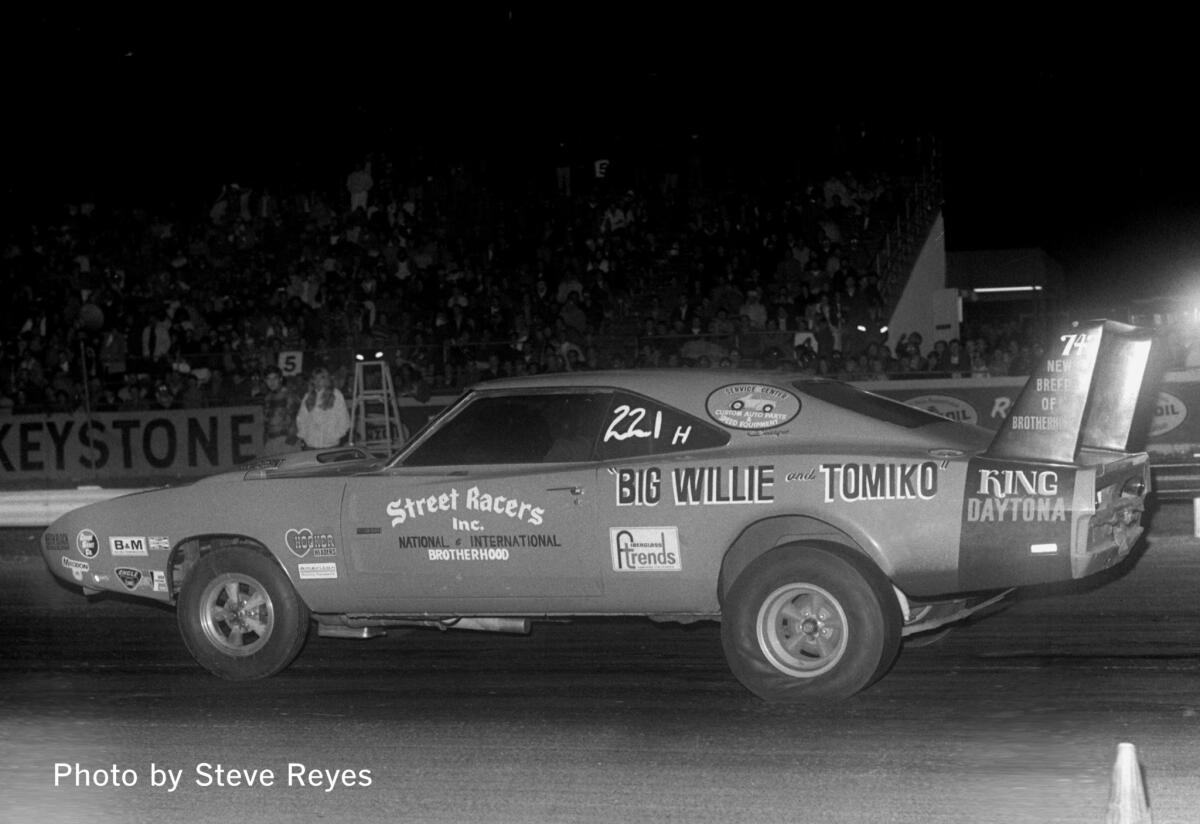

It was parked on a lot owned by Ted Moser, a plain-spoken man who outfits vehicles for films and TV shows. Moser nodded toward the Plymouth and told me Big Willie throttled that car to glory in drag races across the country.

He said I should have known about Big Willie. But back then, in the spring of 2017, I knew neither the man nor the myth.

Big Willie was a 6-foot-6, muscle-bound black man who had come of age in segregated New Orleans and, Moser said, later served with distinction during the Vietnam War. He had come to Los Angeles to escape the sting of racism in the South but, like many African Americans before him, found this city bred its own ugliness and divisions.

He wanted to change that.

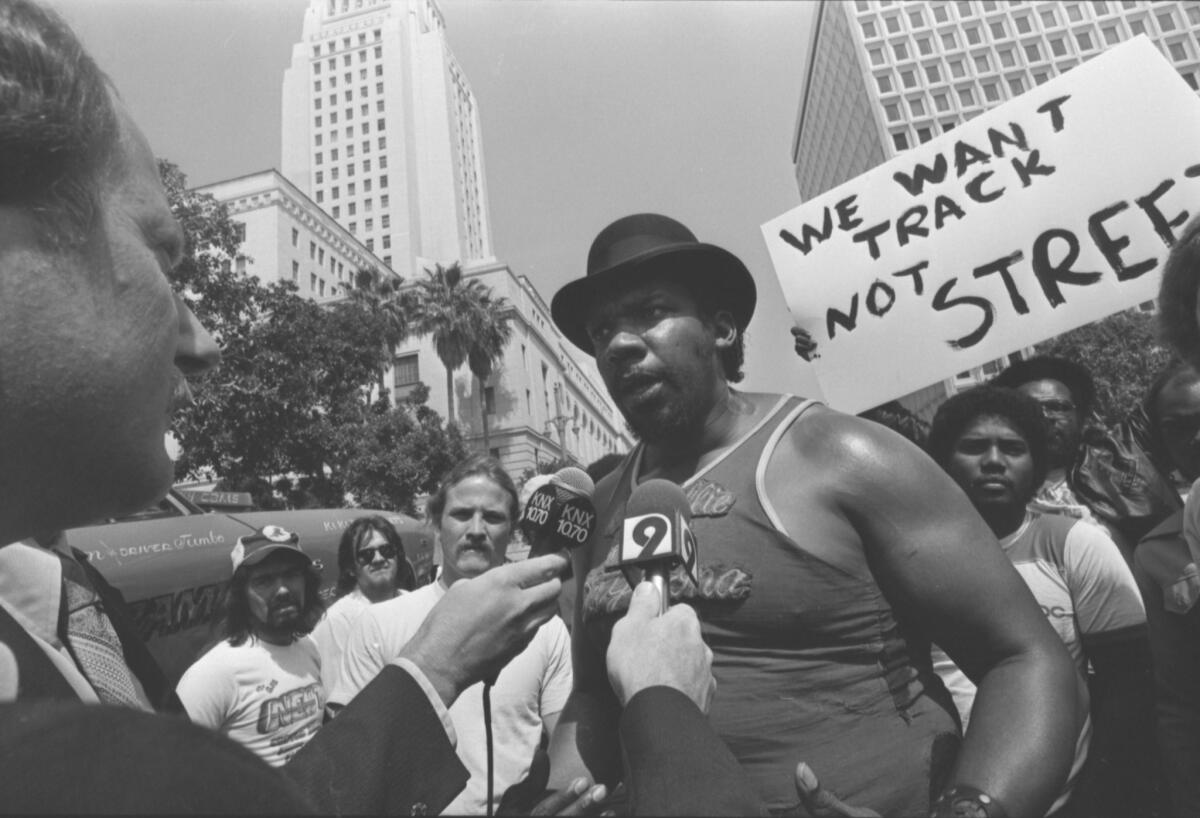

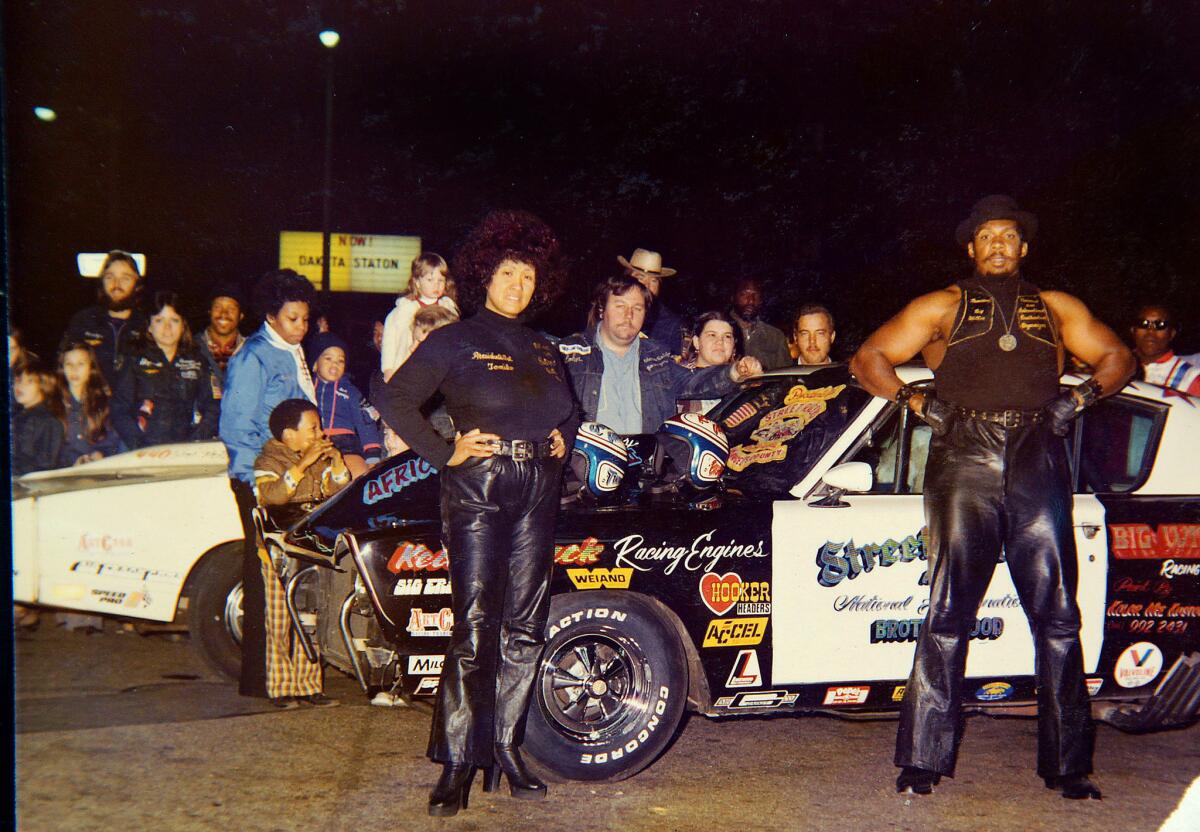

With help from the Los Angeles Police Department, Willie founded the Brotherhood of Street Racers, a group that, starting in the late 1960s, pushed a message that men and women working on engines and racing cars could bring peace to an L.A. torn apart by the Watts riots.

Making street racing safer was his focus, but Big Willie’s swagger and charm seemed made for Hollywood. He acted on the side and befriended stars like Paul Newman. Moser said Willie was even offered the role of Darth Vader in “Star Wars.”

Beginning in the mid-1970s, Willie ran a drag strip on an island in the Port of Los Angeles. His vision of unity flourished there with help from two key benefactors: Tom Bradley, the city's first black mayor, and Otis Chandler, surfer, car collector and publisher of the L.A. Times.

I eyed the decrepit Plymouth, a husk of a car whose paint was flaky and fading. If Big Willie was the legendary figure that Moser made him out to be, how had I never heard of him? And how had this race car wound up wasting away on a dusty lot in Northridge?

That Plymouth — and Moser — set me off on a journey to learn more about Big Willie Robinson and led to “Larger Than Life,” The Times’ new documentary podcast that debuts today.

Download the “Larger Than Life” podcast and see more videos, photos and archives »

Willie may have died in 2012 largely forgotten, but he was an inspiring figure emblematic of a pivotal time in Los Angeles. It was a town of rage and glamour — and the street racer straddled both sides. To fulfill his mission of uniting a divided city, he transformed himself into an outsize character — Big Willie — a figure who was both boastful and earnest in his pursuit of peace. His infectious and grandiose persona helped win over cops and criminals, but it may have been his biggest flaw too.

Among the harried scribbles in my notes from the visit to Moser’s Picture Car Warehouse is something I fixated on long after I left the car lot.

“Willie actually spoke at Chandler’s funeral,” Moser claimed.

If true, it meant that I had an unlikely — albeit distant — connection to Big Willie through Chandler and The Times.

I tracked down the video of the newspaper publisher’s memorial, which was held at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena. About 30 minutes into the service, Big Willie appears — an uninvited man in camouflage fatigues and a black leather vest making his way down the center aisle of the old stone church.

“Otis Chandler meant a lot to me!” the street racer bellows as he rumbles past stained-glass saints.

The mourners look stunned.

“You guys don’t know the story of how Otis brought the streets together, after the Watts riots back in ’65,” he says.

Willie claims that after he served in the Vietnam War, The Times wrote about him, and Chandler gave him the nickname Big Willie. He goes on to say that he used street racing to bring people together to heal a city torn apart — first by the Watts riots and later a long string of scarring upheavals. Many of the 900 or so in attendance were titans of publishing, politics and the patrician set — and it was evident that it was the first they’d heard of this. You can see the skepticism on their faces. But then, something remarkable happens.

“Otis Chandler, on the streets — by gangbangers and everybody on the streets — they knew him as Big O,” Willie says.

Big O is what Chandler’s grandkids called him — and the memorial erupts in applause. Now this story that Big Willie and Chandler had been mixing it up with gangsters and racers in South L.A. seemed incredible — but real.

“We brought the Crips and the Bloods. The Mexican Mafia, the Asian gangs, the skinheads, the Nazi low-riders, high school kids, college kids, all together on Terminal Island, and we said, ‘Let’s stop the violence,’ and drive-by shootings disappeared,” Willie says.

It was clear: These two men from entirely different worlds were bound by the magic of fast cars — and a dream of mending their tormented city.

“And right now, I guarantee you, he’s racing in heaven,” Big Willie concludes to another torrent of applause.

News accounts of the unscripted eulogy focused on what it revealed about Chandler — that the street racer’s presence proved that the mogul had been a man of the people. But the coverage mostly ignored the story of Willie Andrew Robinson III. So, I went looking for it.

Big Willie transcended norms his entire life. He was a black man who bridged gulfs of race, class and culture.

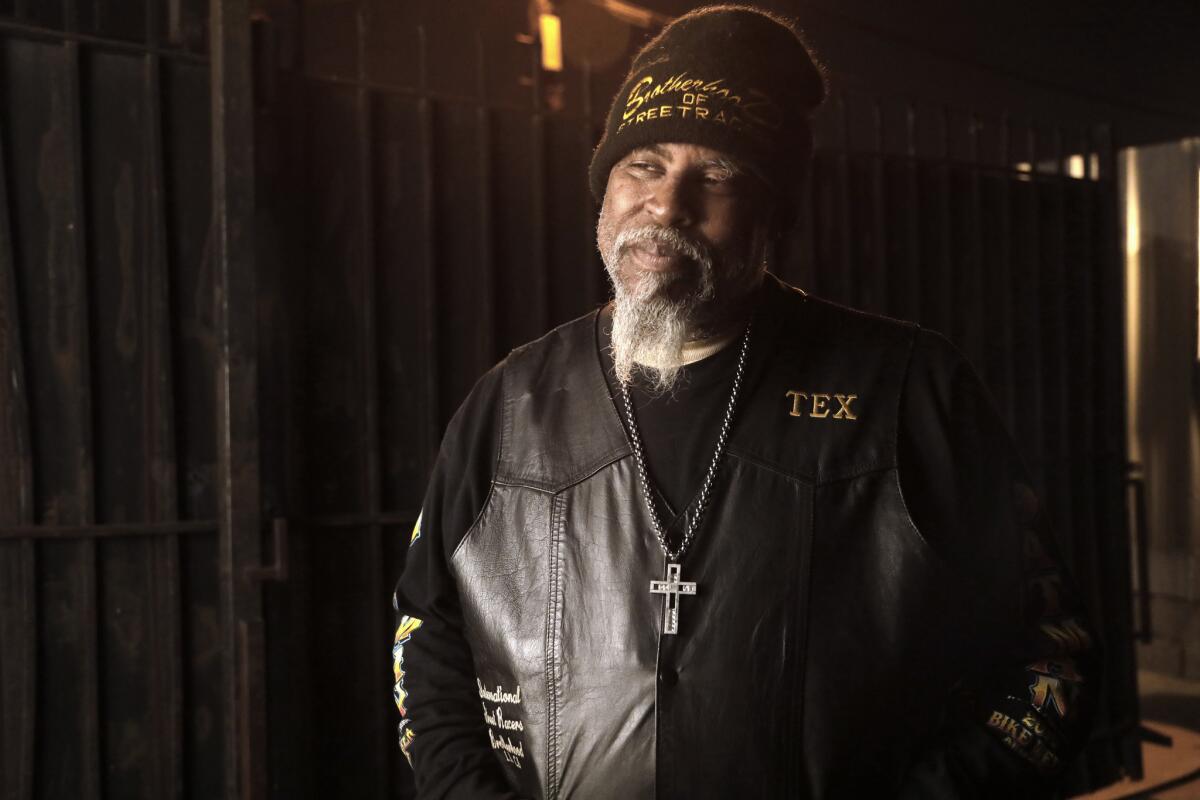

“You could be the Ku Klux Klan, you could be the Aryan Nation, you could be the Crips, you could be the Bloods — when you come around Willie, all that stops,” said Brotherhood member Kennith Russell.

Big Willie gave people an outlet to put aside their differences and to race cars. At first, he did it on the streets of Los Angeles. And later, with the help of his wife, Tomiko, he did it to greater effect at his track: Brotherhood Raceway Park.

The drag strip on Terminal Island began operating in 1975 — and it would open and close its gates often over the next two decades. Street racers and law enforcement officials alike told me that you could find Crips and Bloods forging a peace there one race at a time. At Brotherhood Raceway, there was a strange alchemy of bravery, recklessness and speed that proved surprisingly successful.

‘You could be the Ku Klux Klan ... the Aryan Nation ... the Crips ... the Bloods — when you come around Willie, all that stops.’

— Kennith Russell, Brotherhood of Street Racers member

“I think he’d be the first to tell you how many riots he stopped. How many times he knew both sides and said, ‘Guys, let’s go to IHOP instead,’” said Los Angeles Police Commission President Steve Soboroff. “Big Willie was a service provider. Just like Big Brothers is, just like the YMCA is, so was Big Willie. Big Willie was an off-ramp to the freeway to jail.”

Crime went down, and violence was prevented when Big Willie got involved.

Beat cops said it. Politicians said it.

“He did a lot to get kids off the street,” former LAPD Chief Bernard C. Parks said. “Any time you’re dealing with prevention, you can’t count how many lives were saved. How much damage was prevented.”

Here’s Donald Galaz, a member of the Brotherhood, describing how Willie helped him:

“I lost my way,” Galaz said. “I went back to hanging on the streets — and drinking and drugging. He pulled me aside and he said, ‘I heard a couple things about you, and you need to get your act together again.’ And it stuck pretty deep with me.”

Big Willie went against the grain in so many ways. After his military service — which he said involved covert work in Vietnam as a Green Beret — he returned home to find South L.A. battered and burned by the Watts riots. But amid the violence, he saw street racing as a way to make things safer.

I can relate to Big Willie’s passion for cars. They’re in my blood too.

I come from three generations of L.A. car dealers, starting with my great-grandpa, Meyer; then my grandfather, Louis; and finally my dad, Larry, and uncle, Philip. The business, which was long located in Culver City, spanned seven decades. I worked at the dealerships a few summers during college. And I wondered what it would be like to make a career of it. But my mom, Adrian, always told me she’d kill me if I tried to pursue it.

In the end, the issue was moot — our family got out of the business in 2005 as I was finishing up school.

The dealerships’ shuttering marked the end of an era. That’s part of why I was so entranced by Willie’s story. By telling it, I hoped to reclaim and preserve something that was once so important to me and my family. Soon enough, his saga became my obsession.

I trolled EBay for rare copies of car magazines, like the December 1968 edition of Drag Racing that declared Big Willie the “King of the Street.” I pored over thousands of pages of documents from the Los Angeles Harbor Department — which oversaw the land on Terminal Island that was home to Willie’s track. I filed public records requests with a host of government entities, among them the CIA and FBI. My reporting even took me to a car auction in Indianapolis, where one of Willie’s rides — a 1969 Dodge Charger known as the Duke and Duchess Daytona — fetched $203,500. It’s the only of Willie’s Daytonas still in existence after his famous King Daytona — a ferocious and rare car powered by a Hemi V-8 — was destroyed decades ago.

All of that was illuminating, but in the end, it was those who knew Big Willie that helped bring him to life.

I interviewed more than 100 people, many of them members of Willie’s Brotherhood of Street Racers — a band of gearheads that carries on in his absence, guided by his vision of peace, fellowship and speed. They welcomed me to BBQs at a clubhouse on South Central Avenue. They took me street racing on the darkened roads of Compton. Many of their lives were forever changed by Big Willie — and they were determined to preserve his legacy.

People like Fabian Arroyo knew the man beyond the myth.

With a long ponytail and dense goatee dusted with gray, Arroyo looks like an old-school biker. Arroyo, 55, is a teamster who works in transportation on Hollywood productions. The first time we met for an interview, Arroyo’s voice kept catching — and eventually broke — as he talked about Big Willie.

“Willie’s mission in life was to save lives,” Arroyo said. “We were his kids, and he took care of us and wanted to make sure we lived to be gray and old instead of dying on the streets like everyone else was doing.”

Arroyo is serious about cars. He owns 25 — including a hearse with flames painted on the flanks. Arroyo grew up in Los Feliz, and at 14, he saw his first street race. He was hooked.

Arroyo is part of a vibrant subculture of street racers in Los Angeles — one partly shaped by Big Willie. Every night, somewhere in the city, racers in souped-up rides square off a quarter-mile at a time. It’s electric, exhilarating and very dangerous. It’s also illegal.

A few years after he saw his first race, Arroyo met the man who’d change his life. Unlike most people who admired Big Willie from afar, Arroyo got to know him really well — they were even housemates for a time.

“He was a celebrity,” Arroyo said. “Only a small circle knew him, and I was fortunate enough to be in that circle.”

Arroyo told me about Willie’s relationship with Chandler. It began in earnest, he said, with a story about street racing in The Times’ West magazine. It’s the piece from 1966 that Willie mentioned during his speech at Chandler’s memorial. In the story, Willie was described as a “promoter of street races in [the] area of 43rd and Vermont.” There’s a huge photograph of him on the last page, his muscles bulging beneath a tight white T-shirt. It put him on the map, identifying him as a leader of the street racers to the powers that be in L.A. Within a few years, Willie would form an alliance with Bradley and work with the LAPD to stage races on city streets.

Arroyo also talked about Willie becoming a bit-part actor. His brief turn in a 1971 street racing movie called “Two-Lane Blacktop” led to his friendship with Gary Kurtz, one of the film’s producers. Kurtz would go on to make “Star Wars.” Their relationship linked Willie to the space opera — the official “Star Wars” characters were sent to Brotherhood Raceway in 1977 at the behest of Kurtz for a night of racing. The association didn’t end there: Willie boasted he’d been offered the part of Darth Vader in the film, Arroyo said.

Big Willie had other ties to show business: He appeared in TV’s “CHiPs,” and an episode of “Adam-12” was based on his exploits. Willie also said he befriended the likes of Steve McQueen and Robert Mitchum at a South L.A. nightclub called Maverick’s Flat.

But it wasn’t always easy for Big Willie — far from it. In L.A., he experienced a version of racism he’d been forced to endure in his native New Orleans. Arroyo witnessed it firsthand.

“There are people who called him the N-word right to his face,” Arroyo said. “It happened so often, and he would just be polite. And it’d be like, ‘Willie, just kick the guy’s ass!’ And he’d say, ‘Nah, it doesn’t work that way.’ He’d just hit them with kindness.”

That approach may have helped Willie win over authorities in the aftermath of the Watts riots — including politicians and police officials who had overseen the city’s infamously heavy-handed response to the uprising.

‘We did something that had never been done before: We used racing — racing! — to stop killings.’

— Big Willie Robinson

Arroyo recorded an interview with Big Willie at his home in Inglewood in 2009. His aim was to document Willie’s lifework. Listening to the tape reveals his passion for his mission:

“We did something that had never been done before: We used racing — racing! — to stop killings,” Big Willie said. “We’re in history.”

Before long, I was chasing Big Willie’s ghost, crisscrossing the Southland to meet with those in the street racer’s long, elliptical orbit. Highways knifing through the sprawl and country roads twisting through chaparral — routes I’d rarely traveled became part of my daily drive, the miles obliterated with a soundtrack of Parliament, Curtis Mayfield and other music that Brotherhood members told me Willie loved.

Over the course of a year, I got an education — and then some.

A racer in the Inland Empire shared stories about Big Willie and Chandler — but offered, with a furrowed brow, the warning that sometimes the street racer could ask too much of his benefactor. The man sent me packing with a mason jar of moonshine he’d made.

I met with the son of a street racer in the parking lot of a 7-Eleven in Silver Lake to pick up a box of vintage car magazines. Stories about Willie’s fights with the L.A. harbor commission to keep his raceway open filled the musty pages.

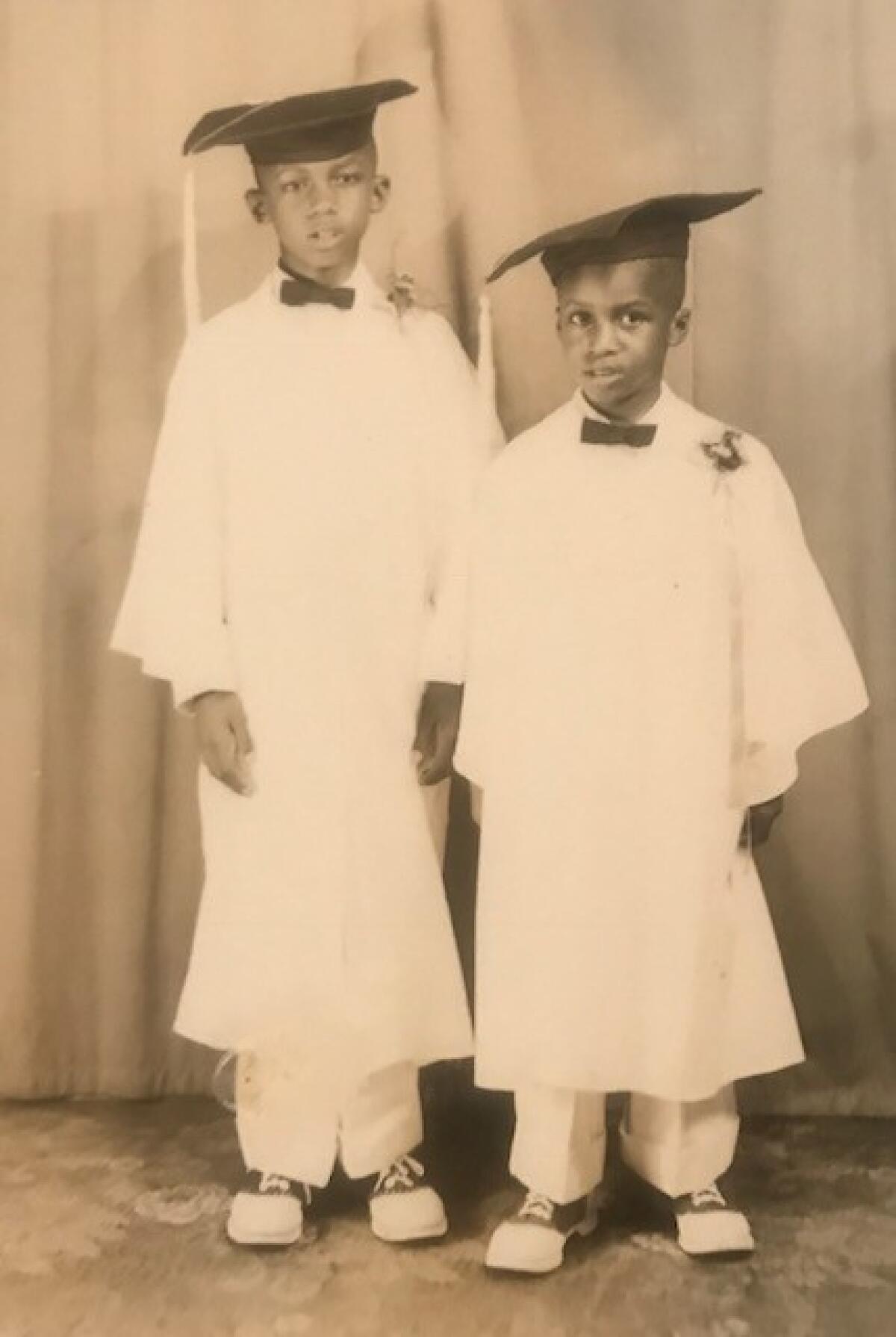

Out in Walnut over a cup of coffee, a high school classmate of Big Willie’s said that as a teenager, Willie dreamed of becoming a doctor. Back then, Willie’s nickname was Texas Slim — he’d been tall and lanky. The man laughed hard at this, his eyes crinkling behind his big, red aviator eyeglasses.

In the Palm Springs area, the wife of a producer friend of Willie’s talked about a movie the street racer made with Paul Newman. She brought out her husband’s old Brotherhood jacket, which was dotted with patches, including ones of a racer being chased by a cop car.

Buried in these conversations about carburetors, high school dreams, broken promises and Hemi V-8s, a phrase kept cropping up. It would be intoned like a benediction: “Run Whatcha Brung.”

That was Big Willie’s motto. It meant that at a street race or his track on Terminal Island, all were welcome, and any vehicle — and any person — could get a race. But for Willie, it wasn’t just about racing — “Run Whatcha Brung” became his life’s credo. It became his rallying cry in a city beset with racial strife.

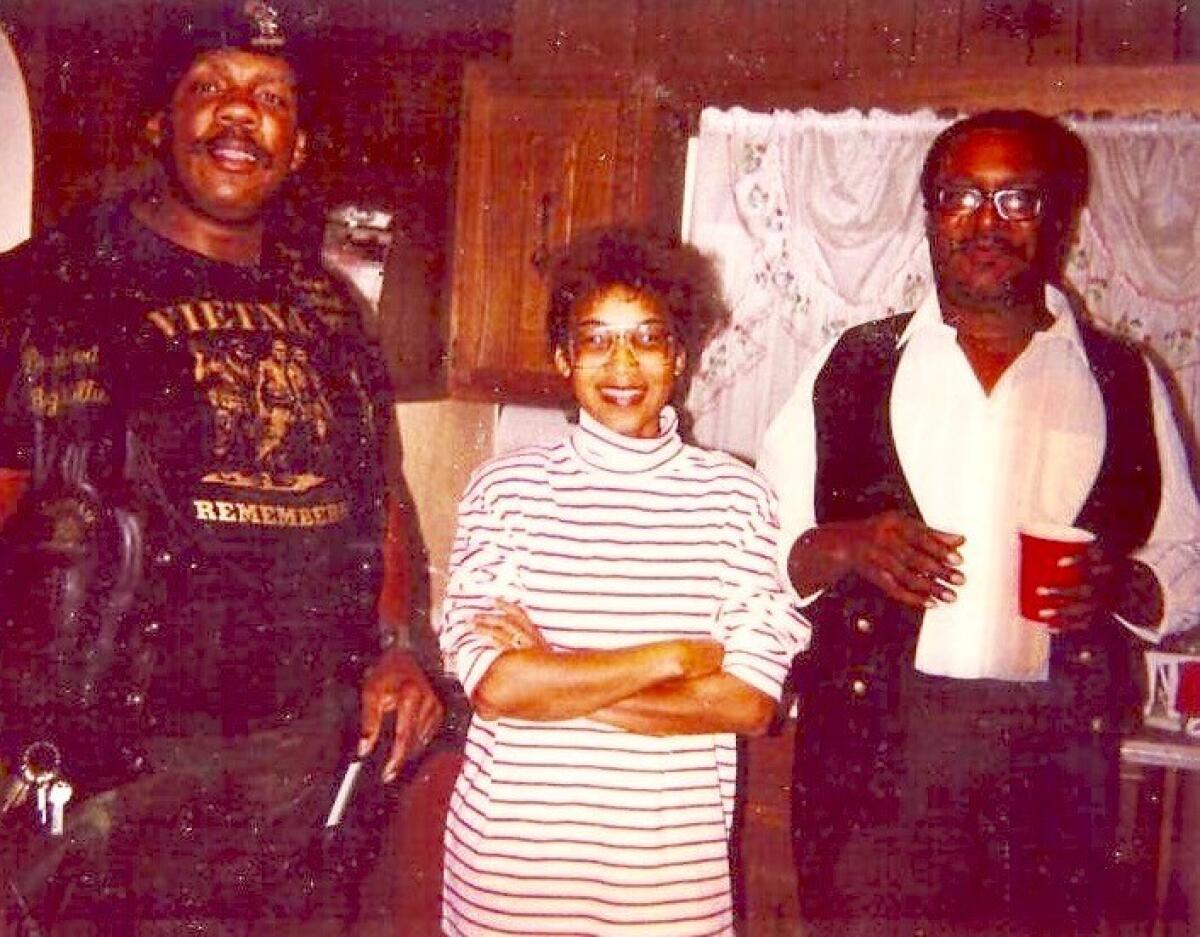

To try to understand how he became someone who adopted this outlook, I had to talk to his family. And of all the interviews, one that really stuck with me was a conversation with the street racer’s little brother, Don Ray Robinson.

Robinson answered the front door of his Fontana apartment in a wheelchair and a Raiders T-shirt. He explained that he was a diabetic and had lost toes to amputations. I asked him about his and Willie’s childhood.

“We weren’t rich or nothing like that, but we had nice clothes, food on the table and everything,” Robinson said.

They grew up in a big New Orleans family, five kids in all, raised by Lula Mae and Willie Robinson Jr. Born in 1942, Willie was the oldest. Their mother was the loving protector, and their auto body repairman father was a stern taskmaster. When the brothers acted out or failed to live up to expectations, they’d be sent to work at the body shop, Robinson said. So working for their dad didn’t necessarily kindle a deep love of automobiles for the boys. Because it was painful. Robinson showed me his scars from years of sanding cars.

“Look here, I don’t have no fingerprints,” he said.

Robinson told me their parents separated in 1958 and later divorced. I was starting to get a sense of how Big Willie became the man he was. Maybe he stepped in to become a father figure to a horde of street racers to give them support and guidance that he didn’t get. Two years later — after Willie’s Oldsmobile 98 was destroyed in a racially-motivated attack — he was sent to live in Los Angeles, Robinson said. It was a logical choice: During the Great Migration, L.A. was among the most alluring destinations for black Southerners. Upon his arrival in 1960, Willie didn’t have much. But he brought some good advice from his grandmother, according to Willie’s sister, Jean Davis-Hatcher.

“She always said, ‘There is no such word as can’t. You can do anything,’” remembered Davis-Hatcher. “Or she would say, ‘Can’t is dead.’”

The land of make-believe was the perfect place for him to transform himself from Willie Andrew Robinson III into the mythical Big Willie. That transformation would come after a riot unraveled L.A., a tycoon took an interest in his illegal activities and the LAPD cooked up a radical idea.

Tracking the arc of the legend would lead me down a path of surprise and tragedy. It’s a tale we’ll finish here in the weeks ahead.

Download the “Larger Than Life” podcast and subscribe to the Play Next newsletter to be among the first to listen to new episodes.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.